| In five days, the US will hold its 60th Presidential election. It's an important one. But before the country lurches toward more political chaos, I want to take a moment to ask a practical, even nonpartisan question. Why isn't Election Day a federal holiday? Or more specifically, why are so many schools closed on Election Day even though most parents still have to work? I admit that as a mother of two preschoolers who'll be home on Tuesday, this is a pet peeve of mine. But the more I think about it, the less anything about Election Day makes sense. Why is it held on a Tuesday, anyway? In what world did the US government think this was even remotely practical?

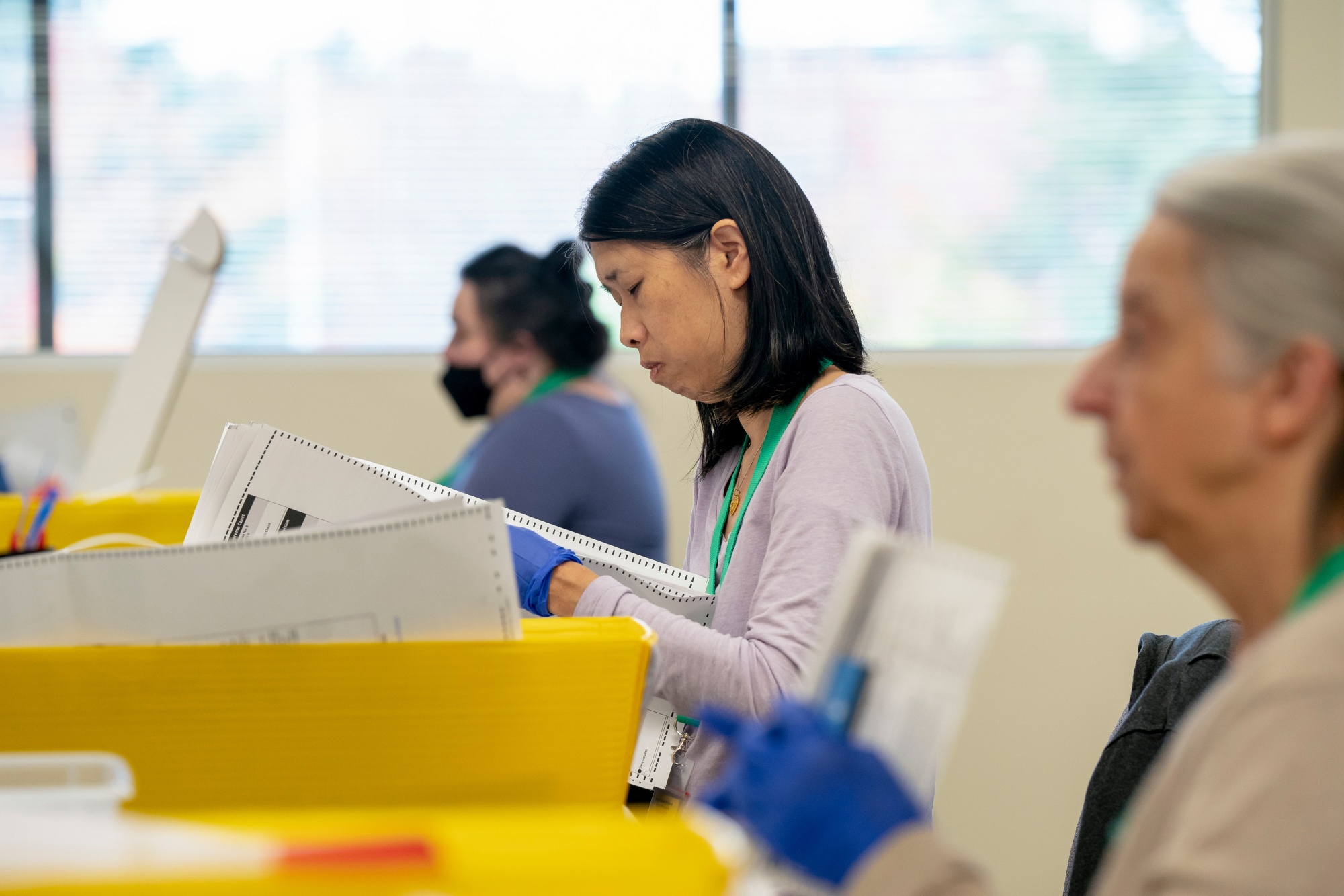

So I looked into it. It turns out that Tuesday was actually incredibly convenient — for men in the 19th century. In 1845, Congress passed the Presidential Election Day Act in an attempt to streamline what had been a pretty confusing election process. Until then, states had been free to hold elections whenever they wanted within a 34-day period that ended in early December. The problem with that method was that, similar to our primary election process today, the states that held their elections early tended to influence voters in states that voted later. The Presidential Election Day Act tried to fix this issue by forcing states to vote simultaneously.  Farmers looking at ballots posted outside of schoolhouse on Election day in McIntosh County, North Dakota, in 1940. Photographer: John Vachon/Library of Congress At the time, the most common occupation for American men was farming. (Slavery still existed and women couldn't vote, so the only people whose voting needs were considered were White men.) Elections couldn't be held in the spring, summer and early fall because farmers were too busy either planting their fields or harvesting their crops. But by November, they were probably done for the year.

Farmers often lived far away from their polling places and needed a full day to ride into town to vote. Many of them went to church on Sunday, so weekend voting didn't work. Wednesday was market day, so it was out as well. Tuesday, however, was likely to be convenient for the most number of people. So that's what Congress went with: "the Tuesday next after the first Monday in the month of November." It was a thoughtful decision, really.

The problem, of course, is that 179 years later we're all still voting to accommodate the needs of 19th century farmers. More than 80% of employed Americans now work on weekdays, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It can be difficult for people to take time off in the middle of a workday to vote, which is why over the years states have enacted early voting periods, allowed for mail-in ballots, extended poll hours, and so on. By spreading voters out over a longer time period, states are also reducing the likelihood that voters will have to wait in long lines on Election Day. A few states even require employers to give workers paid time off to vote.

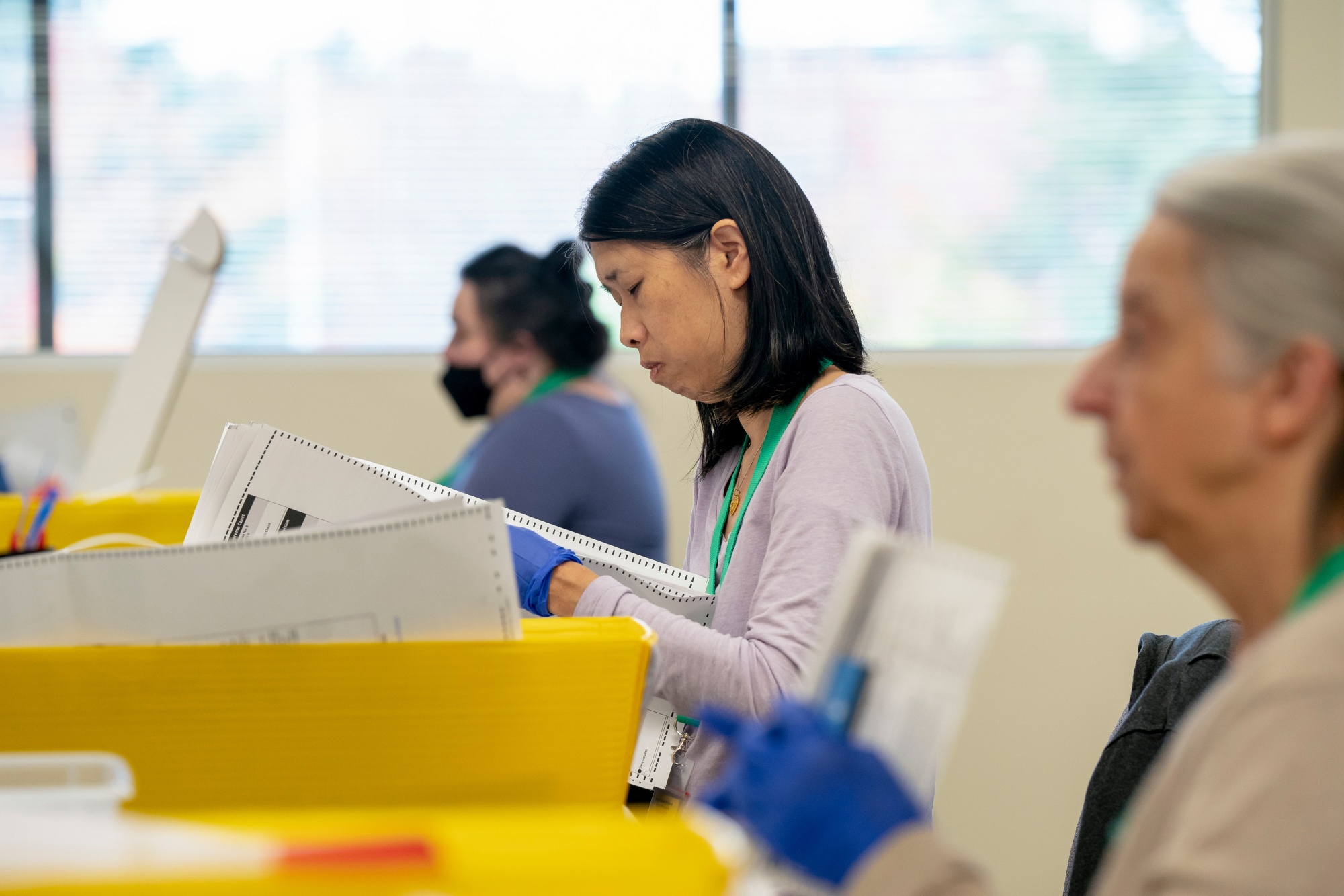

Working people aren't the only ones who benefit from these changes, by the way. People with disabilities, or who need assistance getting to the polls, also need extra time. I had a baby just a couple weeks before the 2022 midterm elections; rather than stumble, sleep-deprived and newly postpartum to the polls with a newborn, I voted by mail.  Election workers organize ballots to be counted in Renton, Washington, on Oct. 28. Photographer: David Ryder/Bloomberg Over the years there have been repeated efforts to make Election Day a federal holiday. The most recent attempt happened in February when California representative Anna Eshoo re-introduced her Election Day Holiday Act, which — like her previous attempts in 2018, 2021 and 2022, is currently stalled in Congress. "Even though I have a lot of years under my belt in Congress, I really thought this issue would be somewhat of a no brainer," Rep. Eshoo told me. "But it wasn't." Senator Mitch McConnell made fun of it on the Senate floor in 2019. "Just what America needs, another paid holiday," he quipped. "This is the Democrat plan to restore democracy?" Advocates for making Election Day a federal holiday usually frame the issue as a way to increase voter turnout. The US has notoriously low voter turnout; even in 2020, when an unprecedented 67% of voting-age citizens cast a ballot for either Joe Biden or Donald Trump, the US ranked an embarrassing 31st out of 50 OECD countries in voter turnout, according to the Pew Research Center. But it's not clear how much turning Election Day into a federal holiday would really improve voter turnout. In both 2016 and 2020, being "too busy" to vote was only the second most common reason people gave for not voting, behind the brutally honest, "not interested." But do you know what making Election Day a holiday would do? Help parents. Because while most working adults may not have Election Day off, many children do. This year for example, public school students in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Detroit, Dallas and Washington, DC, just to name a few, are off school. I took a very informal poll of a couple dozen parents I knew and found that 75% of them have children who're out of school on Election Day, even though more than 80% of them said they still had to work. You might be asking yourself, as I did earlier this week, why do kids have the day off school when they're too young to vote? It's not for the benefit of teachers — in many of the school districts I mentioned above, students have the day off but teachers are expected to come in for a "professional development" day. Instead, schools close for safety reasons. Many public schools double as polling sites, especially in large cities. Beyond the logistical issues that come with repurposing a gymnasium or cafeteria for an entire school day, there are genuine safety concerns when everyone is granted access to an elementary or middle school. "Schools are getting more security-conscious about the general public having access," Ken Menzel, then the general counsel at the Illinois State Board of Elections, told Teen Vogue in 2016.  Men and women at voting poll in New York City in 1922. Source: Library of Congress "We have some concerns regarding the safety of students," echoed Gustavo Reveles, a spokesperson for an El Paso public school district last week. The school district hadn't received any credible threats, Reveles told a local news station; rather, the concern was that schools that operate as polling sites can't lock their doors.

Locked doors are a common school safety protocol because of mass shootings. In fact, the final report issued by the Sandy Hook Advisory Commission in 2015 urged all schools to install doors that can be locked from inside. "The Commission cannot emphasize enough the importance of this recommendation," it stated. (The advisory commission also found that assault weapons "have no legitimate place in the civilian population" and should be outlawed.) And so here we are, voting on a Tuesday because it was a good idea in the 19th century but keeping kids home from school because mass shootings are a threat in the 21st. Regardless of the outcome on Tuesday, the next US Congress is unlikely to address either of these problems. When I asked working parents how they planned to deal with kids who're off school for Election Day, I received a range of answers. Those who had to commute to an office said they planned to either use a vacation day or hire a babysitter, at the cost of a couple hundred dollars. One mother said she'd make use of her company's back-up child care benefit, which costs considerably less. A mom of teenagers said she'd just leave them home alone. But most people said they planned to tough it out while they worked from home. "Lots of screen time," one mother of five told me. Beyond that, she didn't know what to do. "Still trying to figure that out." |

No comments:

Post a Comment