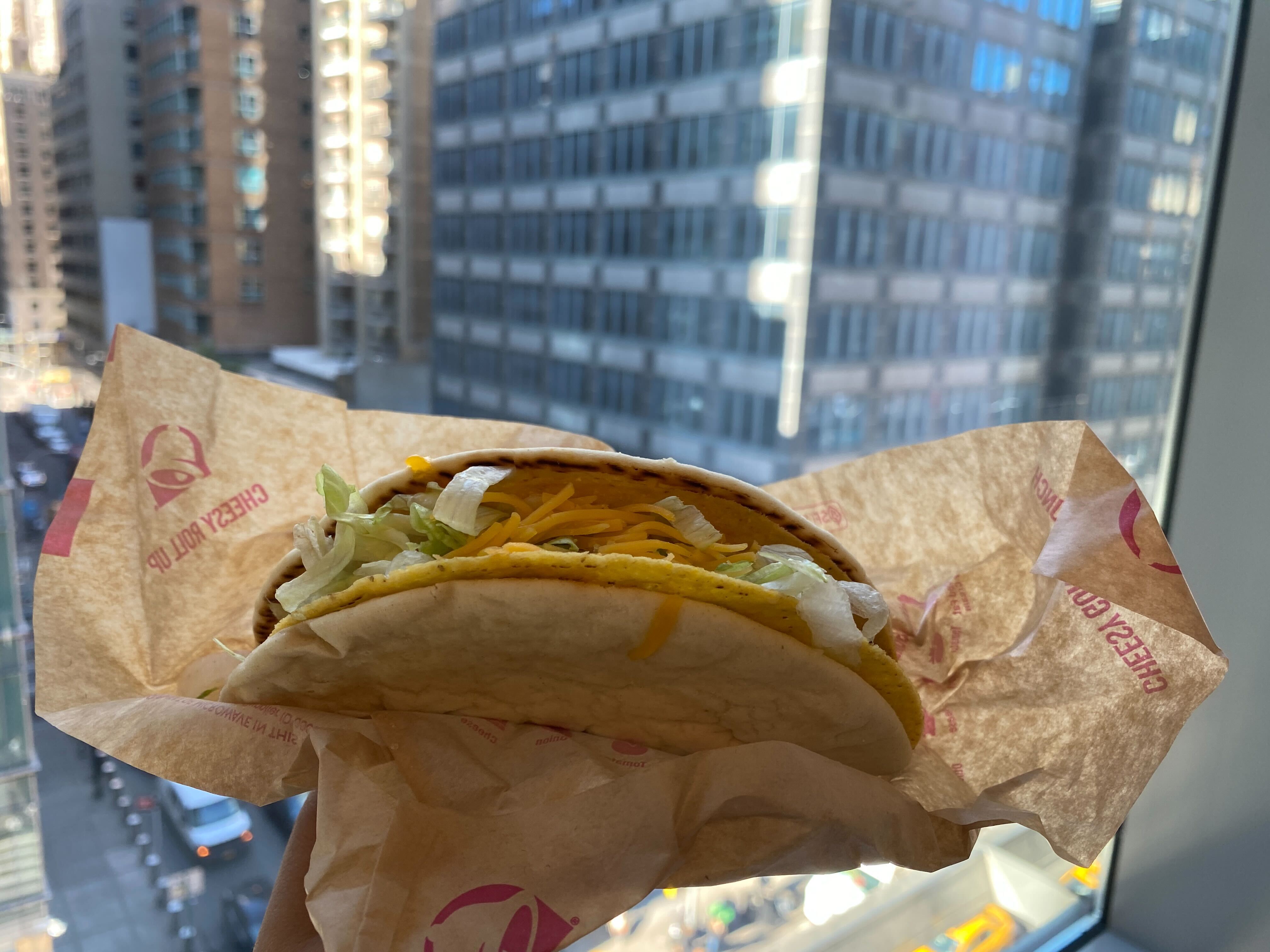

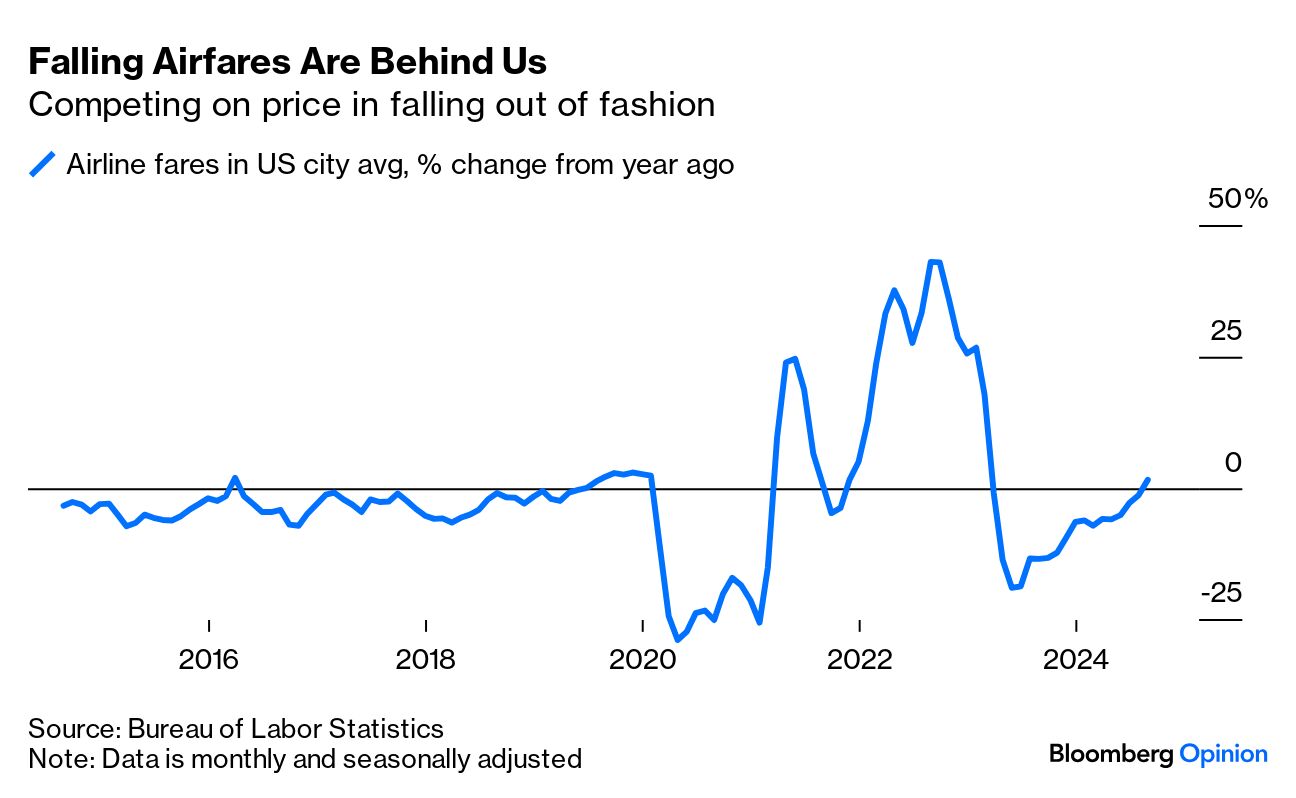

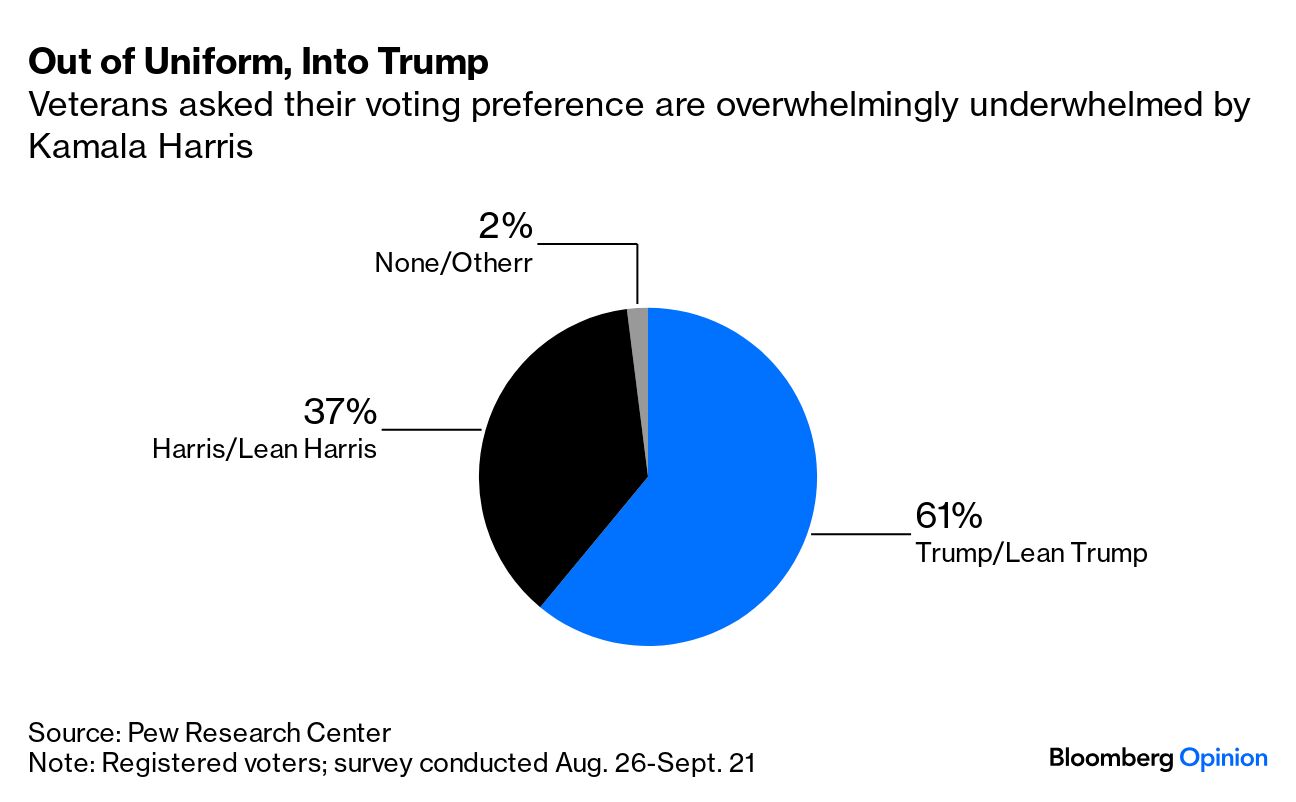

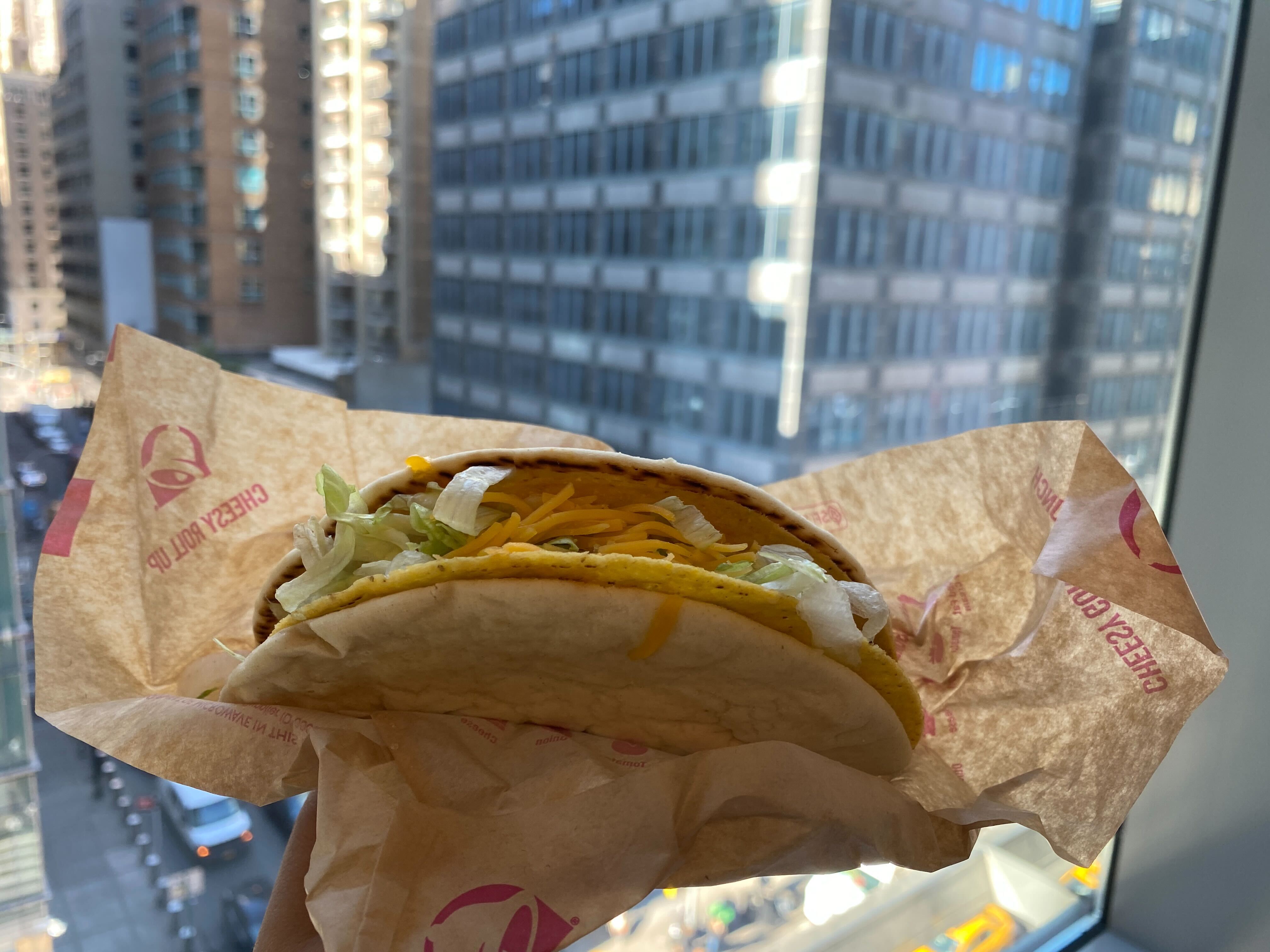

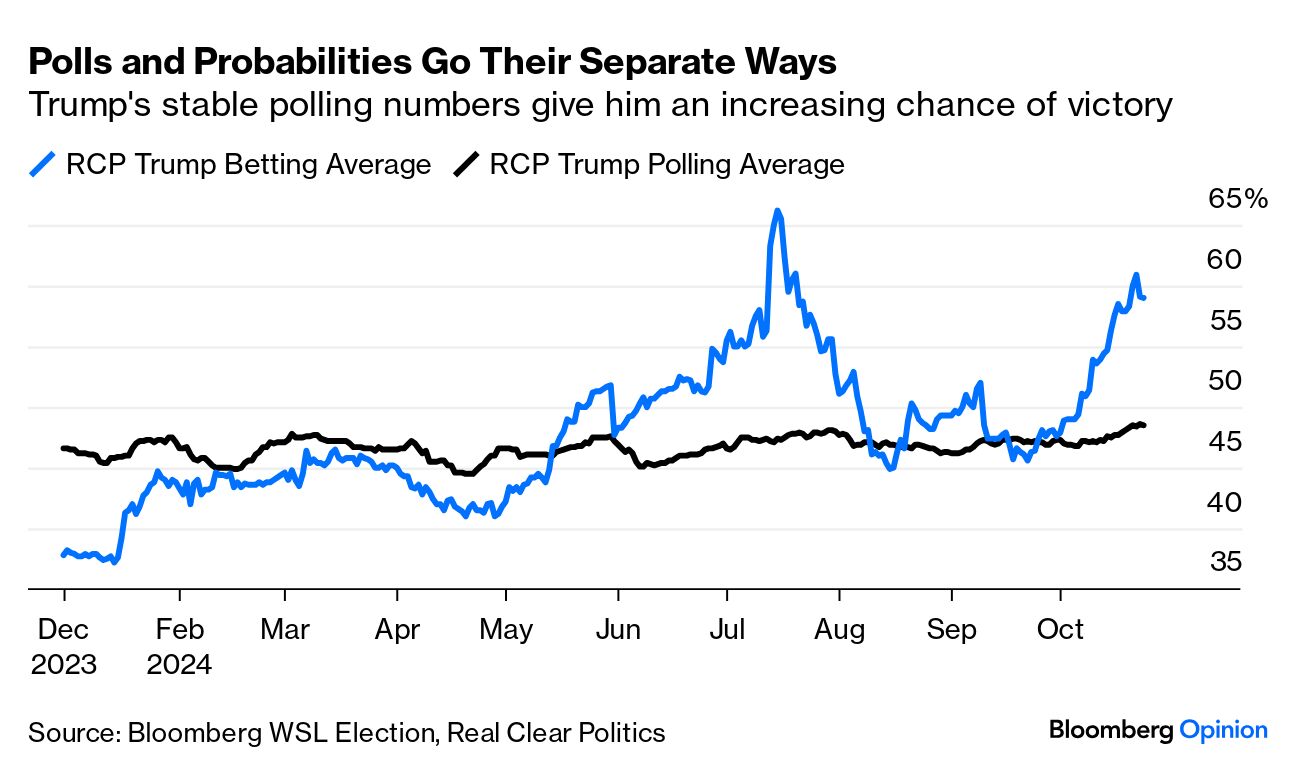

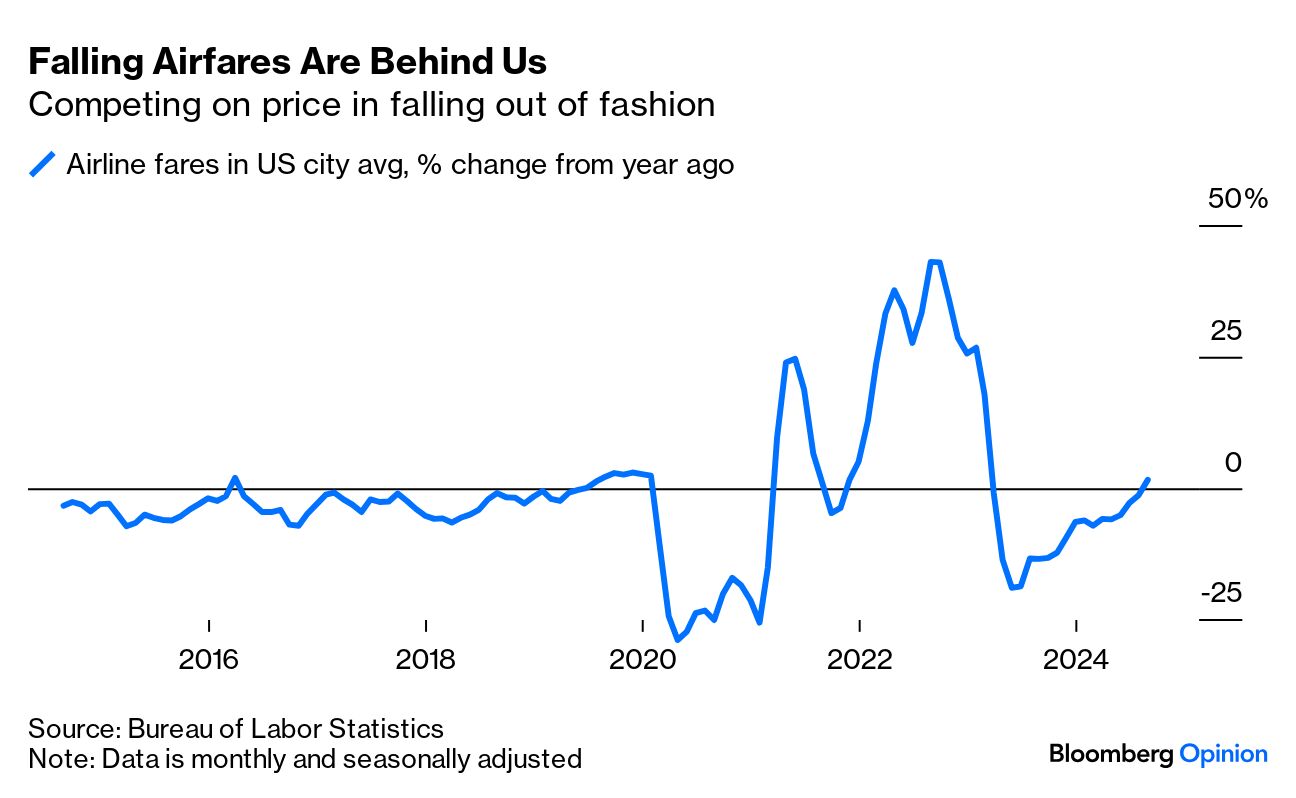

| This is Bloomberg Opinion Today, the average predicted vote share of Bloomberg Opinion's opinions. On Sundays, we look at the major themes of the week past and how they will define the week ahead. Sign up for the daily newsletter here. The paradoxes of Donald Trump's popularity are too many to name, but let's try a few. Why are Black and Hispanic voters trending toward a man who said some of the marchers in a rally led by White nationalists were "very fine people"? Why do working-class men favor a guy who took his family's real-estate empire into six bankruptcies? Why do half of White women support a man held liable for sexual assault? Why do former servicemembers back a man who reportedly called the war dead "losers" and said, "I need the kind of generals that Hitler had"? I recently got an email from a reader that I think helps explain another paradox: Why, given all the positive economic news out there right now, is Trump still crushing Kamala Harris among voters who put the economy at the top of their concerns? "Economists speak in terms of inflation," my correspondent reminded me, "while voters live in a world of prices." Bear that in mind as we enter the last week of the campaign. Inflation, we are repeatedly told, is "tamed" — but a gallon of milk that cost less than $3 in 2020 costs nearly $4 today. Car insurance premiums are up an astounding 47% over that period. Chicken breasts rose from $3.26 a pound to over $4. And that Cheesy Gordita Crunch you absolutely need at 3 a.m. on Saturday — or, if you're me, 2 p.m. on a Friday — costs about twice what it did in 2020!  Writing this newsletter is the perfect excuse to eat Taco Bell for lunch. Core inflation data excludes volatile food and energy prices, but voters don't have that luxury. So, what world will voters live in a week from Tuesday: the one inhabited by economists or the one in which eggs cost twice as much as they did four years ago? Perhaps the free hand of the market — in the form of online betting sites — can point us in the right direction. "It's time to review exactly what Polymarket and other exchanges like it can and cannot do," writes John Authers. They can do quite a lot, it turns out: The gap between the average predicted vote share for Trump and the average probability put on his victory in betting markets isn't as bizarre as it looks. "In a tight election, a small shift in national vote can change the probabilities quite dramatically," John explains. "A 10 percentage point move in probability is equivalent to a move of 0.4 percentage points in the predicted vote share. This is particularly true as the mathematics of the Electoral College, with several states being very close, mean that a common small swing can tip all of them from one column to another." Betting markets have a great track record, but do they also have a pernicious influence? "Like all markets, popular prediction markets are prone to what the hedge fund manager George Soros calls 'reflexivity,'" John writes in a long piece for Bloomberg's new Weekend Edition. "Rather than just reflecting or reacting to facts on the ground, moves in bonds, stocks or oil markets can actually change that reality." Ruh-roh, looks like it's happening already. "Many Americans are frustrated with high consumer prices and elevated mortgage rates, discontent that could help Donald Trump win back the White House, if betting markets are to be believed. Sadly, markets also imply that he'll ultimately make the cost-of-living crisis worse," writes Jonathan Levin. "Mortgage and bond markets are beginning to price in the rising probability that Trump will prevail on Nov. 5 and enact inflationary tariff and immigration policies."  One bonus of the Biden-Harris economy: Fleeing it got very cheap. Maybe not much longer, though, says Conor Sen. "It's inevitable that the market dynamics that have delivered cheaper airfares, used cars and rents in the past year will eventually turn around. One high-profile reminder came from United Airlines' earnings last week. The carrier cheered investors with its rosy earnings outlook, part of which came down to confidence that struggling low-cost rivals won't bring back — and may keep cutting — unprofitable capacity, pushing up prices," Conor writes. "Airfares rising as carriers are scaling back flights suggests that businesses and households are feeling the effects of high borrowing costs in the wake of the Federal Reserve's past policy tightening."  GDP can seem like a gossamer abstraction. But should Trump win, a downturn in economic growth could be a very tangible disaster. "Trump argued that there was no need to worry about the debt created by his spending and tax-cutting plans because economic growth would bring in more government revenue," writes Allison Schrager, but most economists are skeptical about that. Which brings us to the paradox of Trump's bestest word: Tariffs. "Voters generally view economic performance during Trump's first term favorably," writes Bill Dudley. "This time around, if Trump wins the election and enacts his tariffs, the consequences will be much greater. The Tax Foundation estimates that the average tariff rate could increase by 700% by the end of 2025." If that sounds absurd to you, look no further than Trump's steel tariffs during his first term: Bill says they "increased costs by $5.6 billion and created about 8,700 jobs. That's about $650,000 per job each year." At least those rare steel jobs are probably safe in the era of artificial intelligence. "Companies and institutions in the more fluid and competitive sectors of the economy will face heavy pressure to adopt AI. Those not in such sectors, will not," writes Tyler Cowen. "It is debatable how much of the US economy falls into each category, and of course it is a matter of degree. But significant parts of government, education, health care and the nonprofit sector can go out of business very slowly or not at all. That is a large part of the US economy — large enough to slow down AI adoption and economic growth. As AI progresses, the parts of the economy with rapid exit and free entry will change quickly." Free entry, rapid exit? Eek! For newsletter writers, that's pretty much the job description. Bonus Down to Gambling Reading: - The Inflation Struggle Is Over. Just Don't Tell Anyone — Daniel Moss

- WFH Is Moving to the Suburbs, Where It Makes Sense — Justin Fox

- Can Faith in Elections Be Restored? It's Worth Trying — Francis Wilkinson

- Euro-area GDP, Oct. 30: Europe Can't Kick Its Addiction to Russian Natural Gas — Javier Blas

- UK budget, Oct. 30: — UK Mortgage Lenders Dodge the Budget Logjam — Marcus Ashworth

- China official PMIs, Oct. 31 — Xi's Stimulus Won't Stay All Thunder, No Rain Forever — Shuli Ren

If economists are wary of oil and food, they should be terrified of acrylic and gouache. "The contemporary art market poses one of the great chicken-egg questions in all of economics," Allison Schrager writes. "Art is inherently difficult to put a value on, because its intrinsic value — that is, paint and canvas — is worth not nearly as much as its value as a piece of art — that is, its aesthetic, the statement it makes, or its scarcity. The work of long-dead artists is easier to value, because it has a price history and there is a finite number of works. With younger, living artists, it is hard to say whether their work will stand the test of time, or how their future work will affect the value of their current work." In sum: "The entire art market is slowing down, but that is particularly true for younger artists, also known as 'ultra-contemporary.' In some cases, prices are collapsing, risking many careers." Howard Chua-Eoan has a personal stake in the collapsing market — in part because he used to work with the great art critic Robert Hughes. "I found a small plastic sculpture dumped outside his office," Howard writes. "The piece, by Japanese pop artist Takashi Murakami, had been sent to Hughes as part of the annual holiday gift program by the family of philanthropist Peter Norton (of antiviral software fame). It was an edition of 1,000 pieces. Hughes didn't care to have one in his sight, with or without a Murakami autograph. Philistine that I am (and recognizing Murakami's anime style), I scooped it up." Look at the cute little guy!  Photographer: Ambrose Wilkerson/Bloomberg "I've checked the prices online over the last quarter century," Howard continues. "At one point, the toy (which opens up to a mini-disc) seemed to be worth nearly $7,000 — though I can't seem to find that valuation now. While there are asking prices as high as $3,000, sales seem to be in the $1,500 range. The trend seems to be downwards as the rest of those 1,000 plastic monsters go to market. Is mine worth more because Hughes the fearsome art critic hated it enough to throw it out? Or is it worth even less because he literally trashed it? I'm not testing the market to find out." That's art for you: Even a zero-dollar investment can turn out to be a bad one. Notes: Please send Murakami cuties and feedback to Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net. |

No comments:

Post a Comment