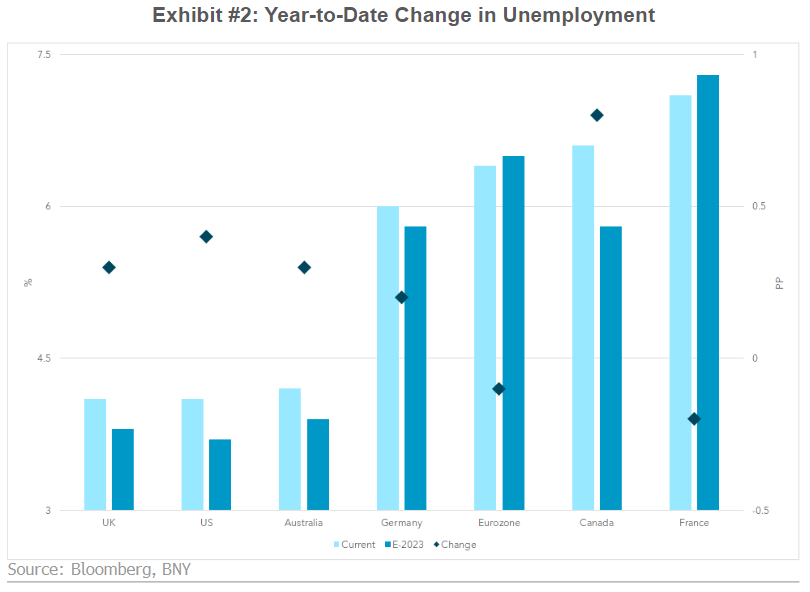

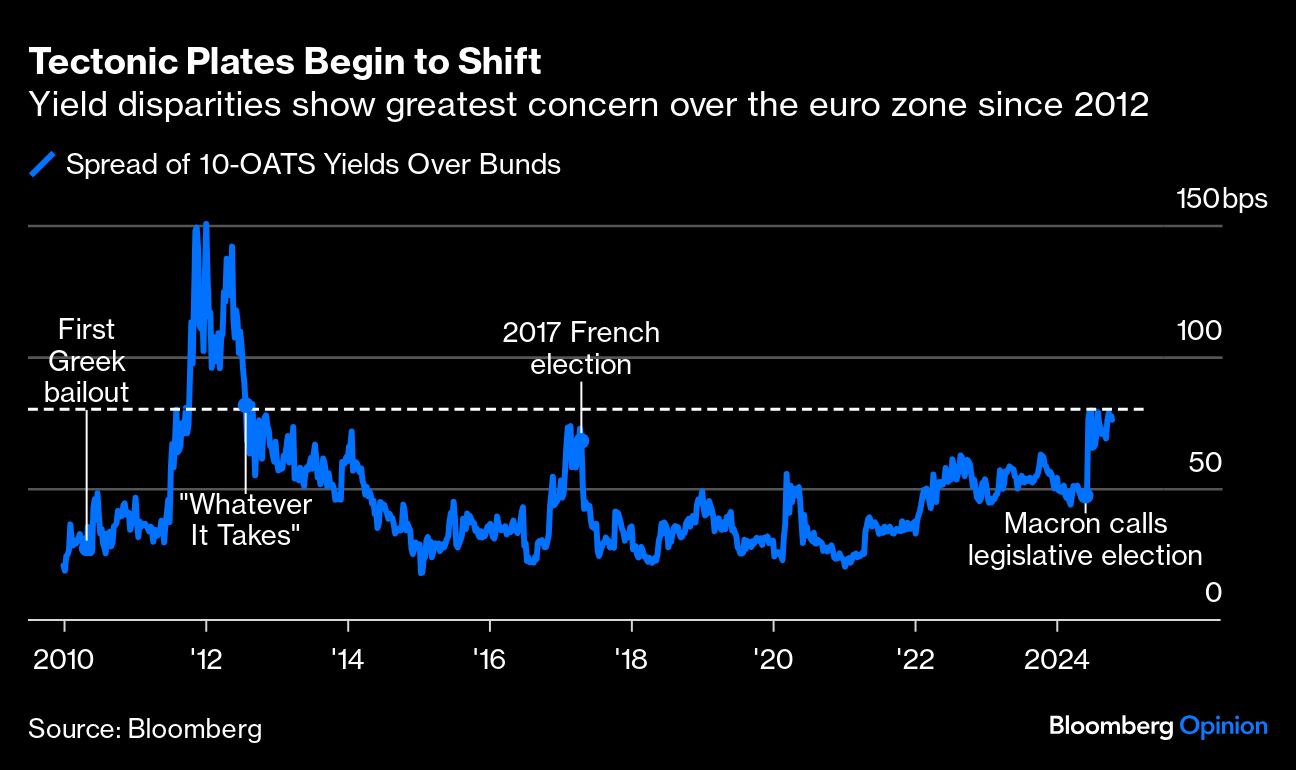

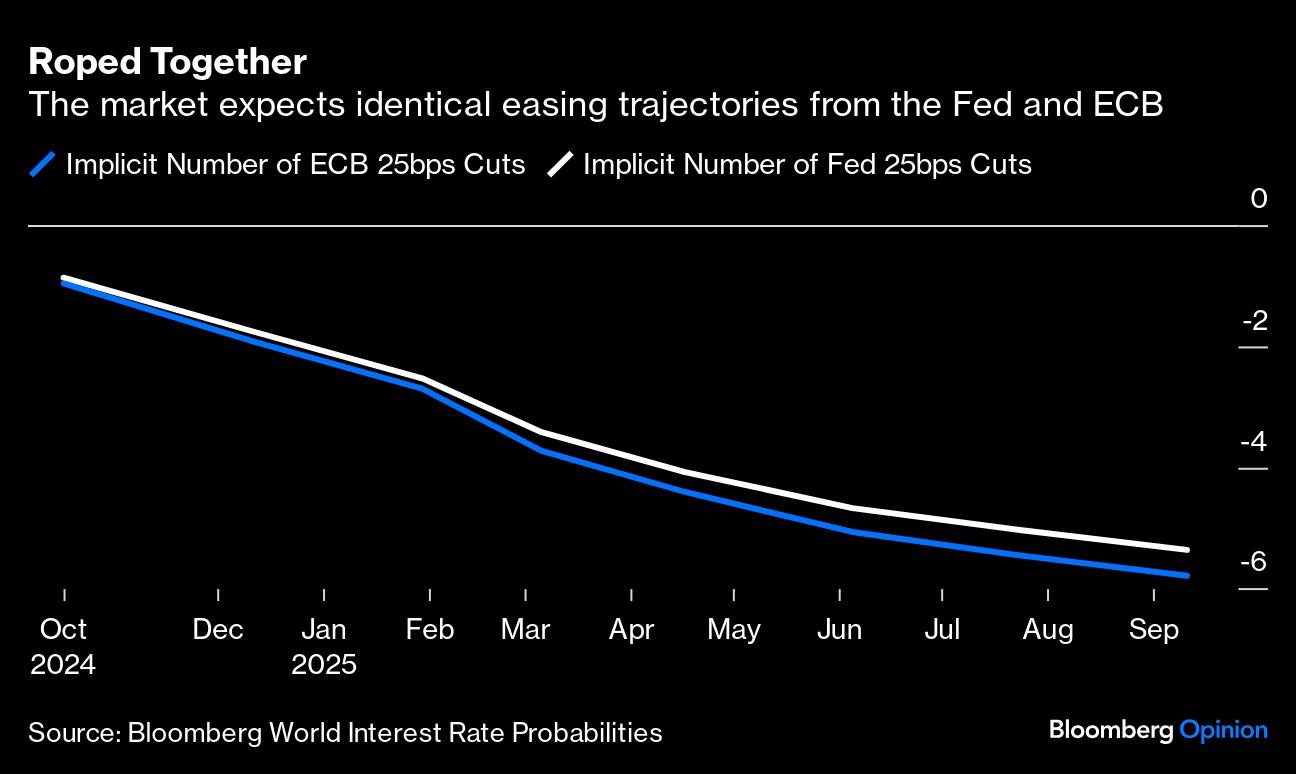

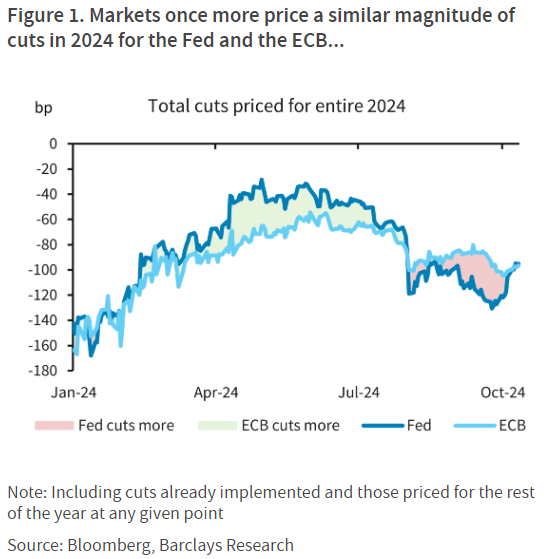

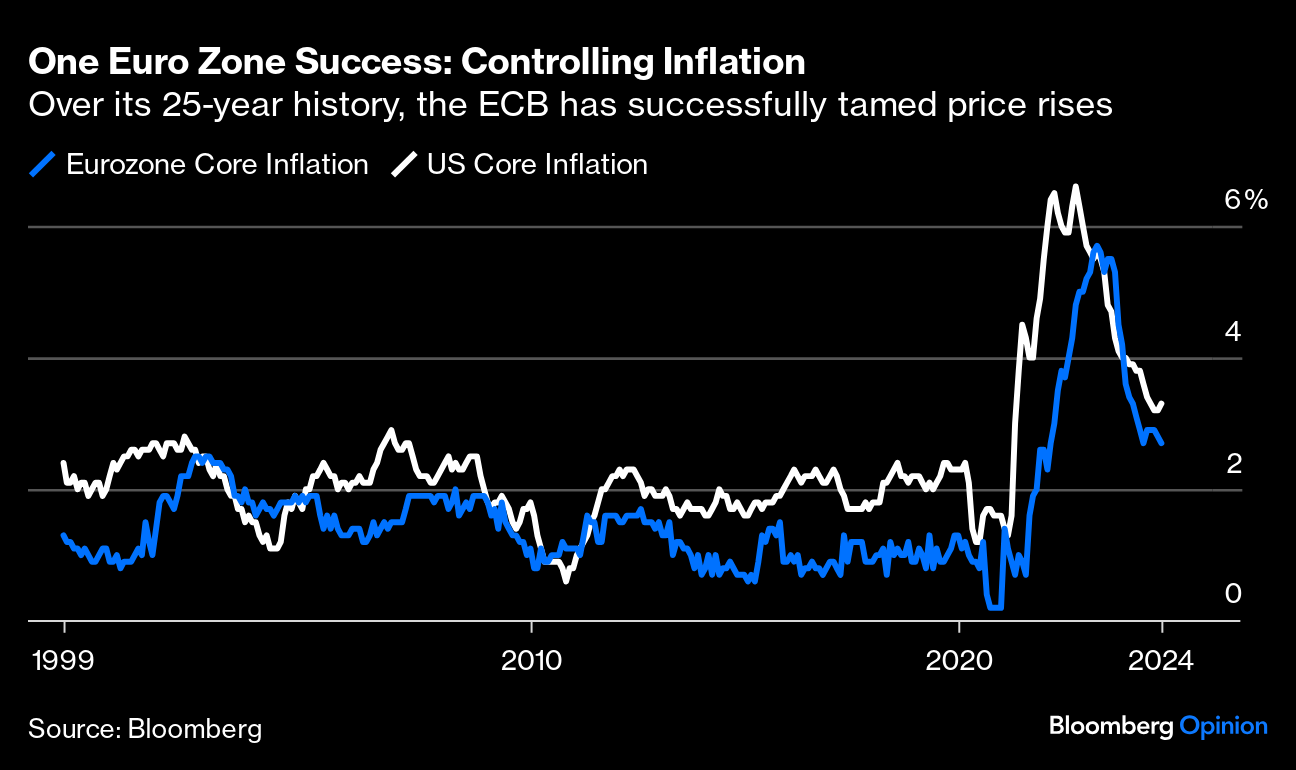

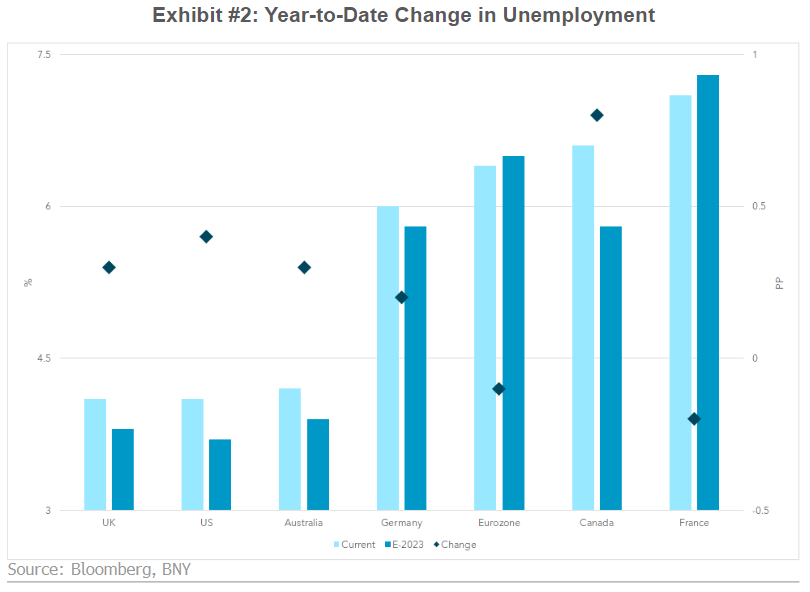

| Europe's saga has taken a new turn. At its last meeting, the European Central Bank seemed in no hurry to cut rates further. Now expectation has shifted to virtual certainty that a rate cut is coming. Indeed, market participants expect the ECB to cut rates in almost perfect synchronization with the Federal Reserve. This is the future as foretold by the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function, derived from overnight index swaps and fed funds futures: This hasn't been a constant. For much of this year, as the following chart from Barclays Plc demonstrates, the market was braced for deeper cuts from the ECB, largely because its economy was in weaker shape. That gave way to a brief fear that the US would need drastic cuts, which has now been corrected: Does this make sense? The prevailing mood of worry about Japanification for the EU suggests otherwise. Unlike the US, European data have disappointed of late. Citi's index of economic surprises suggests that the need for easy money is much greater: Europe's inflation problem looks somewhat better controlled than the US. The ECB still has the genes of the very inflation-resistant Bundesbank. The bloc has been far keener than the US to resort to austerity, and its economy has failed to grow anything like as fast, so it's not surprising that European inflation has been lower for most of the time since the euro was launched in 1999: But as this chart from BNY Mellon shows, unemployment is very significantly higher. The ECB doesn't have a full employment mandate like the Fed, but persisting high joblessness makes it simpler to ease policy. Unlike the US, employment in the euro zone has improved slightly this year:  Yet the problems go beyond the normal issues of inflation and employment. Europe's politics are not propitious for the ECB to be at all hawkish. The economic structure of the euro zone — which forced Mario Draghi to promise to do "whatever it takes" to save the currency from its sovereign debt crisis 12 years ago — is in question again. France's political problems persist. Newly installed Premier Michel Barnier has now submitted a budget to the legislature, but the French fiscal position remains challenged. The right-wing National Rally is forcing a vote on whether to repeal last year's controversial reform to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64, which would be popular with voters, but not with rating agencies. And indeed, Fitch on Friday put French sovereign debt on negative outlook, meaning a downgrade could follow. Fitch was damning in its assesssment: We have raised our fiscal deficit forecasts for 2025 and 2026 to 5.4% of GDP, and do not expect the government to meet its revised medium-term deficit forecast to bring the deficit below 3% of GDP by 2029 (two years later than previously expected). Part of the announced fiscal consolidation measures are likely to be only temporary, while additional spending pressures come from higher spending on defense, renewable investments and rising interest expenses. France's expenditure/GDP ratio is structurally among the highest in our sovereign rating universe, while taxation levels are already very high.

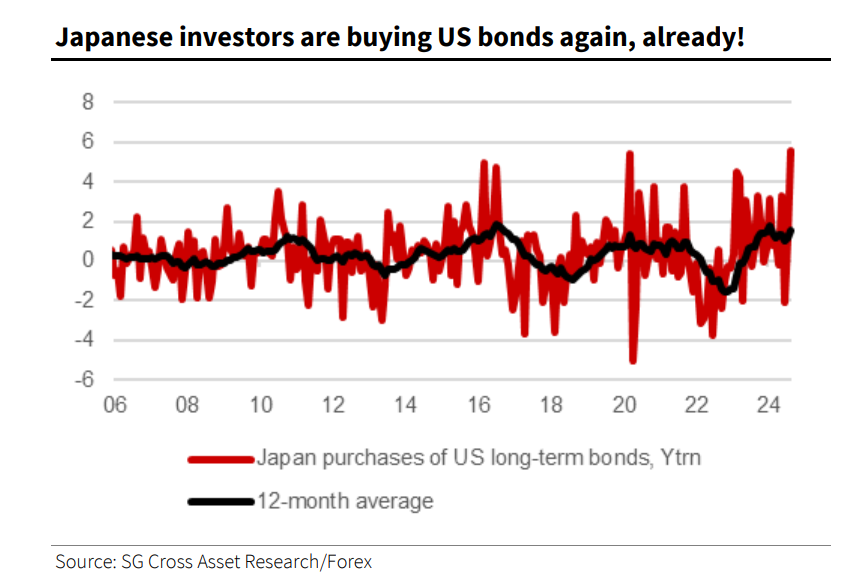

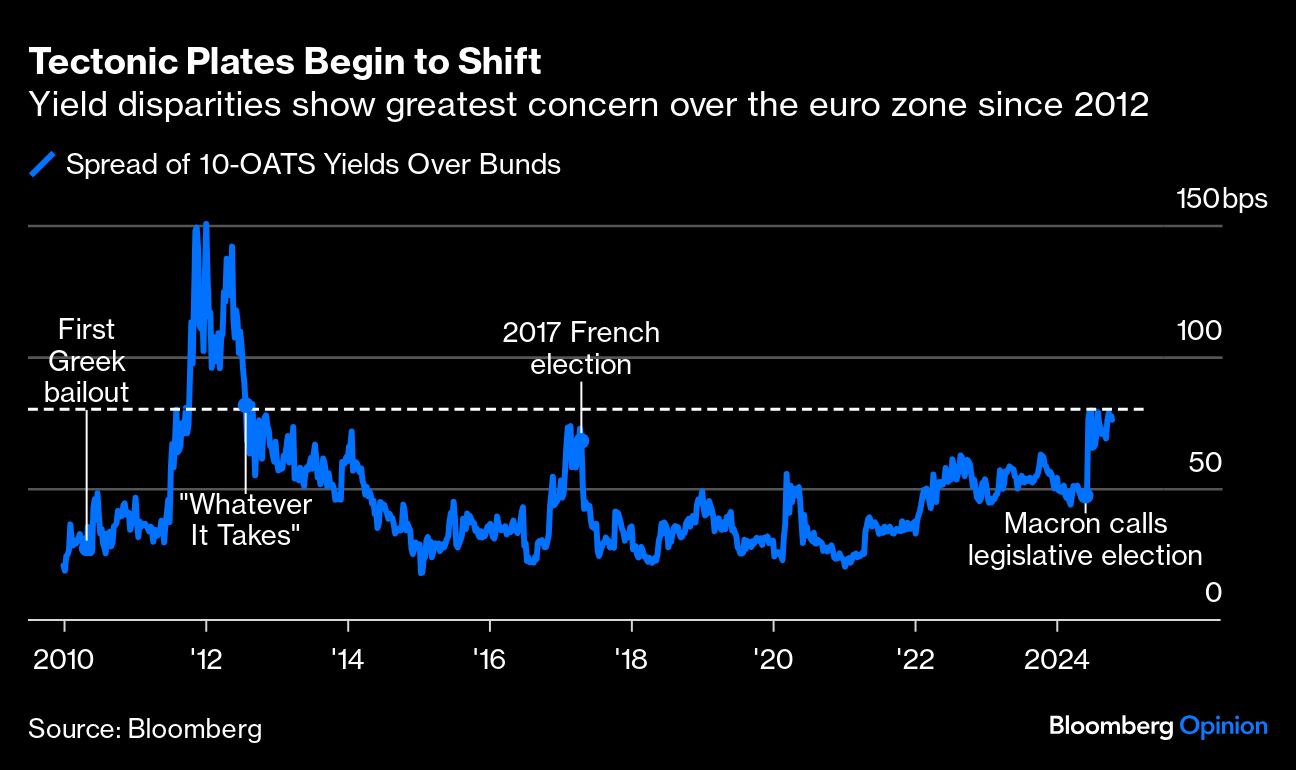

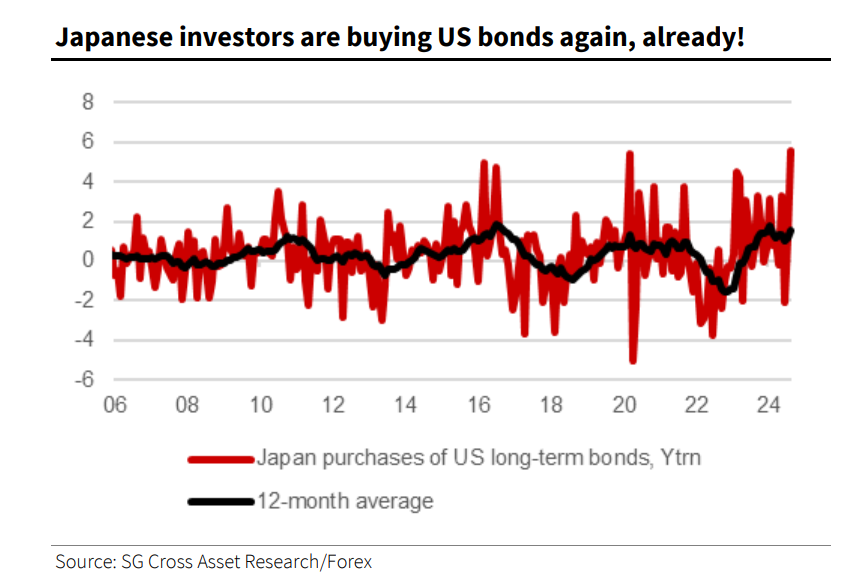

In consequence, the spread of French over German sovereign bond yields, the market's measure of the perceived extra risk, is at almost exactly its level of the 2012 "whatever it takes" moment. Barnier's appointment hasn't brought the spread down:  Italy also faces further rating assessments from Fitch in the next few days. And there are other threats to the euro zone. Poland's Prime Minister Donald Tusk — formerly president of the European Council and a great champion of the European project — created a shock over the weekend by announcing that his country was "temporarily suspending asylum rights." That came after Germany, the EU's single most-important member, announced new controls on the borders it shares with nine countries. This is hugely significant, as freedom of movement is regarded as even more of a bedrock principle than the common currency. Ironically, in 2016, UK Prime Minister David Cameron tried and failed to win concessions on free movement from Tusk as he prepared to fight the Brexit referendum. From here, this looks like a bad time for the ECB to try to be hawkish and demonstrate discipline, while the political risks in the US suggest that the Fed may soon have to do exactly that. The risks for the euro are skewed to the downside. The Japanese yen's wobbly performance is back. It's nearly unrecognizable from the currency turbocharged by July's surprise Bank of Japan rate hike, prompting the carry trade to suddenly unwind. It clambered back to its highest against the dollar in 14 months. But weak performance against the greenback, even after the Federal Reserve started easing with a jumbo rate cut, is now unmissable. And if the recent shift in rate expectations in the US is anything to go by, it's unlikely that the Fed will ease pressure on the yen. With investors now beginning to ask whether the US will cut at all next month, the dollar is surging and stifling other currencies. The yen is on course to break the 150 barrier — a level once thought to be a line in the sand that it appeared too have left behind in August. XS.com's Rania Gule believes passing that landmark again could trigger a wave of yen sales, which would intensify Japanese inflation. As the chart shows, the yen is also close to surprassing its 200-day moving average once more:  The yen's undoing comes from many factors — some of them beyond Tokyo's control. The simple explanation for this course reversal, Societe Generale SA's Kit Juckes notes, is investors buying the dip. Previous Fed cutting cycles have weighed on the dollar, but Juckes notes that this cycle has caused only marginal pain, and investors are already regaining an appetite for dollar assets. Foreign investors have increased their net holdings of US assets by a staggering $40 trillion since 2020, with the dollar still close to a multi-decade high in real terms. Japanese investors' enthusiasm for the dollar, Juckes adds, takes US exceptionalism to new levels:  A strong dollar has its pitfalls for Washington. Juckes argues that the US needs a large devaluation to restore the competitive position of its industry (a position also taken by presidential candidate Donald Trump), but inflows of capital make that increasingly difficult. Is there a lasting solution to this conundrum? The available options are not straightforward: Even a milder version of a 1985 or 2001-style dollar correction as investors cut back or at least hedged their dollar exposures, would be better than the obvious alternatives. As it is, a bird that can't fly or quack probably isn't a duck. And in the same vein, this doesn't look much like the needed dollar correction either. Or at least, not yet. It all reinforces my concern that the fourth quarter is going to be messy, with geopolitical challenges adding to the confusion.

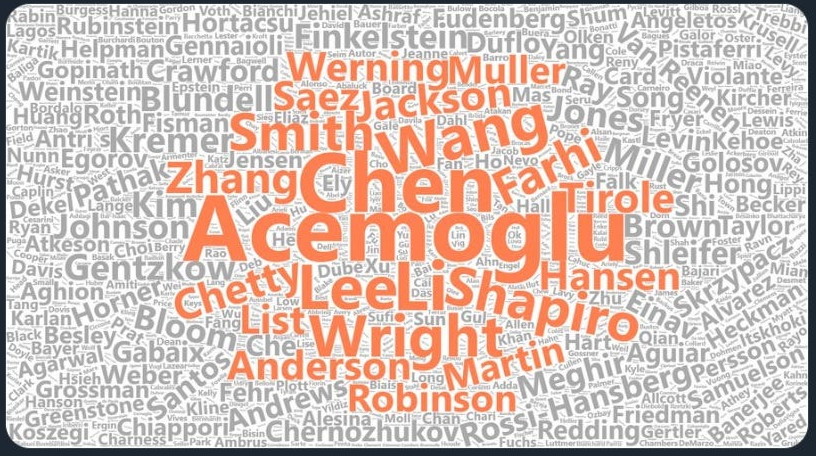

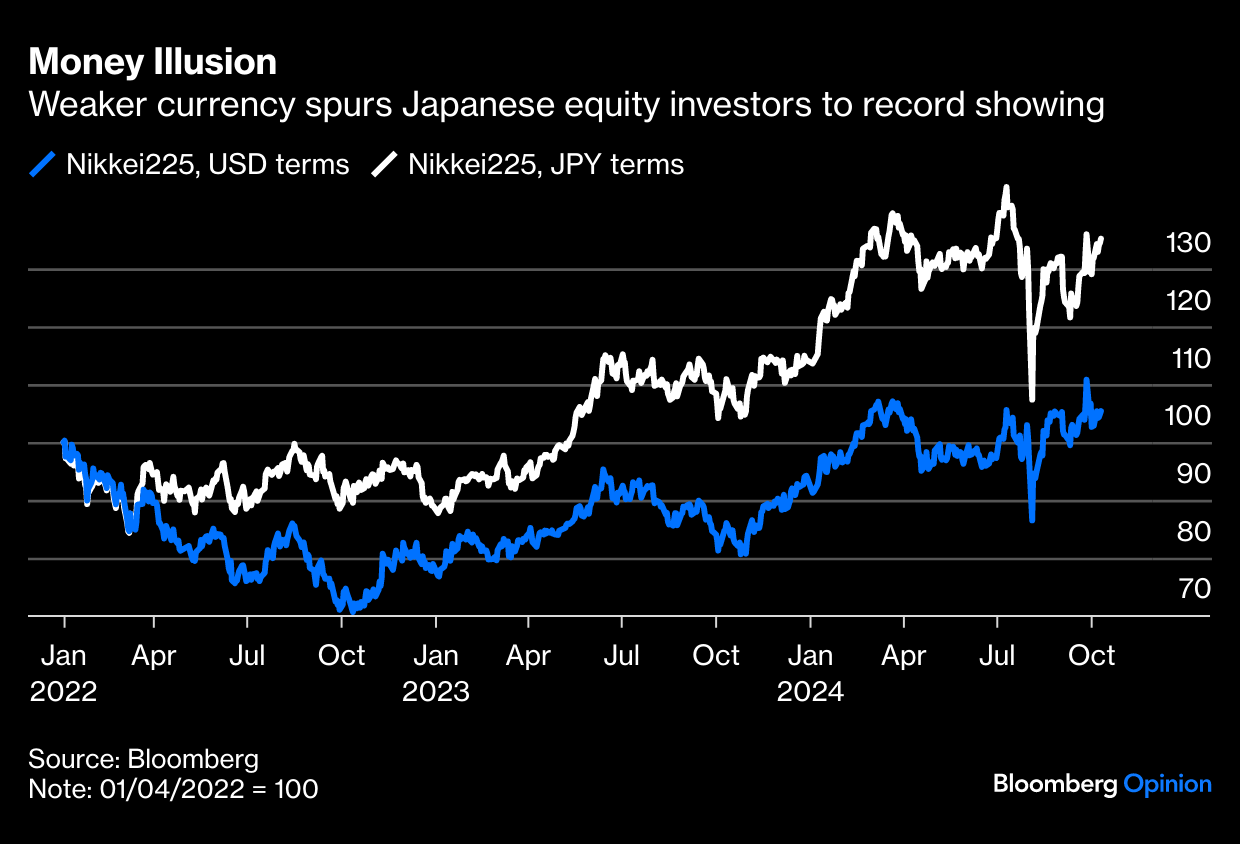

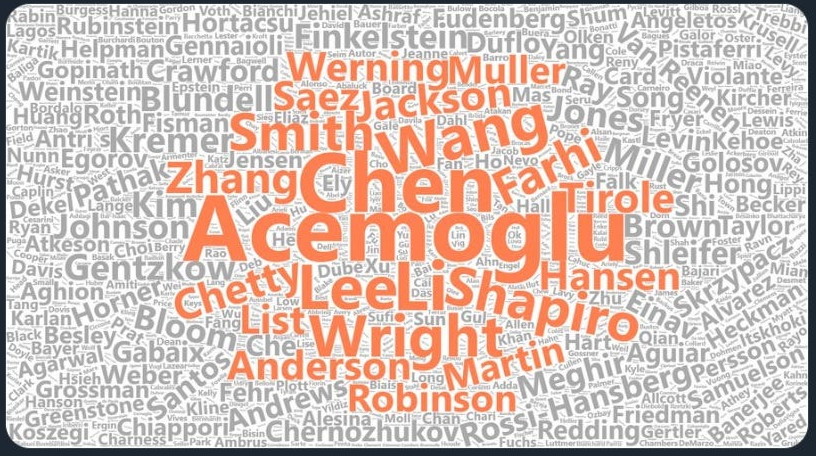

The muffled recovery in the carry trade emphasizes just how extreme August's nosedive was as investors tried to escape the Mexican peso-yen arbitrage with a profit. Some of those problems stem from Mexico itself, where investors are dubious about new President Claudia Sheinbaum, and also worry about the US polls. But it's still remarkable that it's now the dollar, not the peso, which would have generated the most profits against the yen over the last 12 months: After intervening twice to prop up the yen this year, Japanese officials would rather err on the side of caution than be reactive. Most importantly, new Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru's recent dovish remarks conflicted with the Bank of Japan's messaging and with his own position prior to attaining office. That dampened the market's confidence. The BOJ's Halloween meeting Oct. 31 will clarify whether Ishiba's dovishness is confirmed. But it makes sense for officials to keep tabs on events elsewhere. The US electorate will vote and the Fed will meet just a week later. So far, Barclays' analysts believe that the markets, leaning toward Ishiba's narrative, are underpricing BOJ hikes. Ultimately, they see room for higher yen rates and for Japanese bank stocks to outperform, assuming that Ishiba's Liberal Democratic Party and its coalition partners defend their majority in the Oct. 27 election. There is a silver lining of a kind for domestic holders of Japanese equities, in that the Nikkei 225's performance in yen terms has been mighty impressive, but almost all of that has been the effect of the weak yen: It's a near-perfect illustration of the concept of money illusion. View wealth and income in nominal terms, not accounting for inflation, and Japanese assets are doing well. Account for the yen's depreciation and, once more, it's a different story. — Richard Abbey Earnings season for the third quarter is cranking into gear, and we want to know about your earnings expectations for the latest MLIV Pulse survey. Will results succeed in clearing what many consider to be a low bar of Wall Street consensus expectations? And as this latest download of data on Corporate America comes immediately before the US election and the November Fed meeting, we'd like to know which of these events is most important for your investment decisions? And, once the dust settles at the end of December, which sectors and stocks will come on top? Share your views in the latest MLIV Pulse survey, and we'll have the results next week. Congratulations to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson for winning this year's prize for economics in honor of Alfred Nobel. Unlike many Nobel laureates, they have a happy tendency to express themselves, without the use of Greek letters or equations, on subjects that most of us find interesting. And as former colleague Noah Smith pointed out in his Noahpinion newsletter, Acemoglu in particular has a happy knack of being quoted. This word cloud is based on authors cited in five main economic journals from 2005 to 2020:  For a simple and entertaining way to fill up on Nobel-worthy insights, I recommend this most telling passage from Johnson's post-crisis book 13 Bankers, which explains the title. It's a withering attack on deregulation, and how powerful bankers persuaded politicians to let them crash the financial system. Bill Gates felt moved to respond to Acemoglu and Robinson's Why Nations Fail — which grapples with the legacy of colonialism — with this negative review, which provoked the writers into this retort. And more Nobel-related plaudits to colleague Parmy Olson whose book Supremacy has been short-listed for the Financial Times book of the year. It's the story of Sam Altman's battle for supremacy in AI with the CEO of DeepMind Technologies Ltd., Demis Hassabis — who won this year's Nobel for physics. Parmy has already told his story and it's riveting. Recommended reading. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Clive Crook: Tariffs Don't Help Displaced Workers Like Wage Insurance Does

- Tyler Cowen: AI Will Transform Philanthropy, Too

- Marcus Ashworth: A Gilt Buyer Strike Is Not In the UK's Future

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment