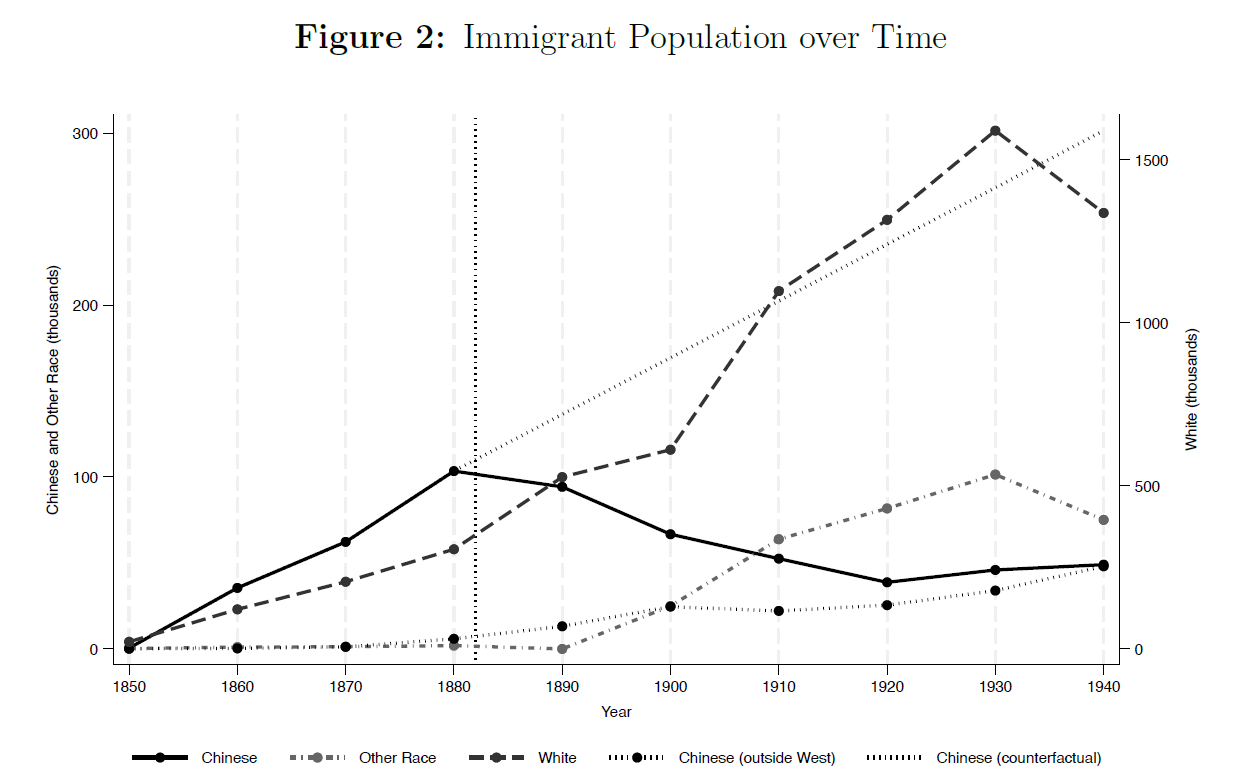

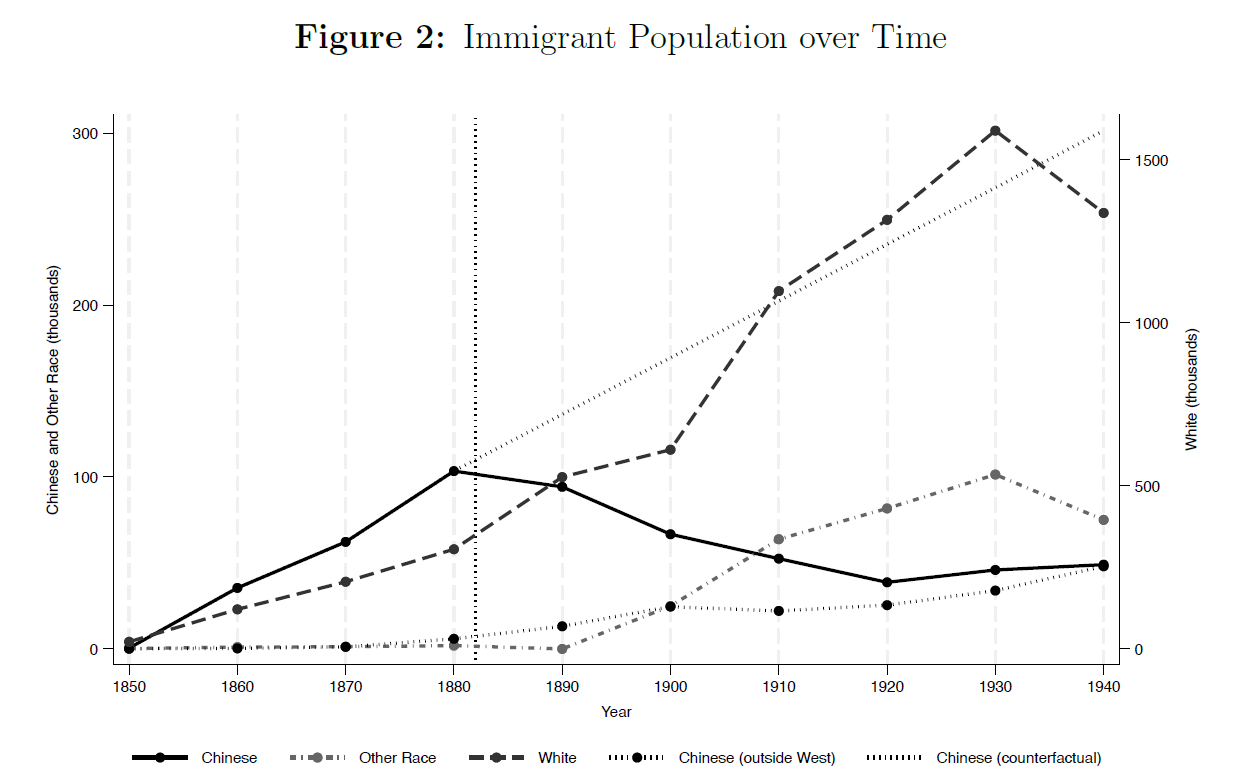

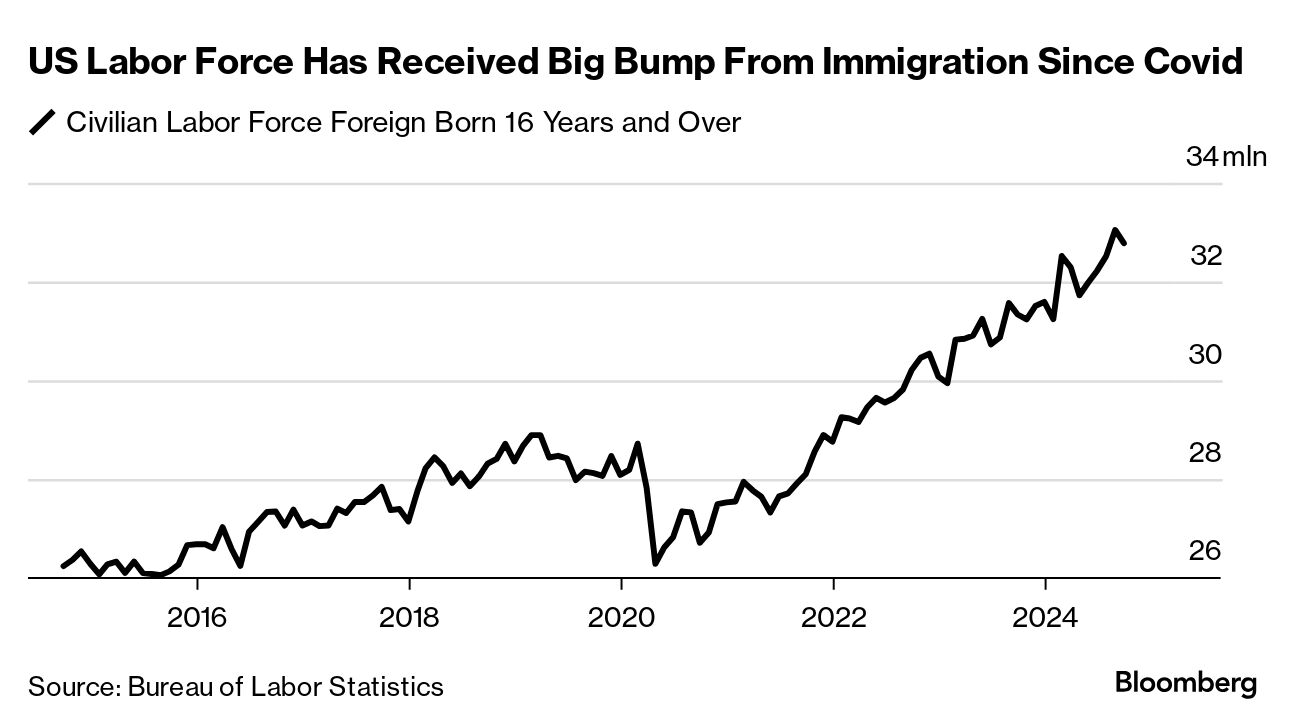

| Perhaps one of the most unpredictable elements of Donald Trump's promises should he be elected next month is to deport millions of undocumented individuals who entered the US without prior authorization in recent years. Wall Street economists have run models on the Republican's tariff-hike proposals, coming up with calculations for their impact on different gauges of inflation and on gross domestic product over set periods of time (the results were almost universally bad for the US economy and its workers). But the same effort hasn't been applied to a mass deportation scenario, perhaps because of questions about whether such a thing could really be organized and implemented (let alone its legal issues and likely need for massive funding from Congress). History, however, does provide some basis for speculation on what could unfold, were he to actually try. Starting in the 19th century, the US began a series of measures to expel the bulk of what had been a critical workforce: Chinese laborers, many of whom came to help build the transcontinental railroad. Later xenophobic legislation barred Chinese, among others, from entering the US. These exclusion acts left the economy of the western part of the US—which hosted almost all Chinese—economically smaller than it would have been, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper released this month. Even more striking: there were net negative effects even for the intended beneficiaries: White workers. The paper serves as a clear warning of unintended consequences from such stark policy actions.  Construction workers in New York City. An influx of immigrants eased pressure in the tight post-Covid US job market. Photographer: Justin Lane/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock After US Pacific and Atlantic coasts were connected by rail in 1869, racist calls arose among Whites to ship Chinese workers back home. Ethnic Chinese were accused of stealing jobs and depressing wages, particularly during economic downturns in the wake of the transcontinental project. Politicians in California—today known as a bastion of progressive liberalism—led the charge. The state's 1879 constitution even included an article barring corporations from employing "directly or indirectly, in any capacity, any Chinese or Mongolian." Racism proved popular nationwide, and in 1882 the US Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act with an overwhelming majority. The move affected a group that constituted 12% of the male working-age population of the western US, according to the NBER paper by economists Joe Long of Northwestern University, Carlo Medici of Brown University, Nancy Qian at Northwestern's Kellogg School and Harvard Business School's Marco Tabellini. An "exodus" of Chinese immigrants ensued, while conditions were made difficult for those that remained, the economists wrote. "We find that the act reduced the Chinese labor supply by 64%."  Source: Joe Long, Carlo Medici, Nancy Qian and Marco Tabellini, from US Population Census. The researchers found that one group of workers did benefit: White men who were born in the West and worked in mining. But that was more than offset by the hit to the overall labor force size, which limited economies of scale and reduced overall productivity. The legislation ended up restraining growth in the West for decades, the authors concluded. The West, which relied on labor-intensive production at the time, saw manufacturing output reduced some 62% compared with what would have been, the analysis showed. That curtailing of economic activity diminished the incentives for some new labor that would have flowed to the region from the East, which held the vast bulk of the US population at the time. "More White men would have moved to the counties where the Chinese lived," the economists wrote. In all, excluding the Chinese caused 28% fewer White Americans to come West to work and thus harmed incomes, compared with what would have been the case without the immigration law, the authors wrote. The broader negative economic impact lasted "until at least 1940." (It wasn't until 1965 that Chinese were finally allowed to move to the US in large numbers again.) Fast forward to today. The Republican Party's campaign platform published in July echoes the xenophobic laws of more than a century ago, proclaiming in a nod to the party's White far-right base a call to deport "millions of illegal migrants." That was several months after a new analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office indicated that the surge in immigration seen since the pandemic—much of it involving unauthorized entry—would boost the US economy by about $7 trillion over a decade. Most economists agree that migrants have been behind a notable portion of the surprising strength in payrolls through the most aggressive cycle of Federal Reserve monetary tightening in decades. In the run-up to the Nov. 5 election, one oft-cited complaint is that the surge of immigrants in recent years is straining government budgets. Indeed, a number of mayors and governors have pressed Washington for more federal assistance to cope with the costs to accommodate the added millions who have arrived in the country. However, net-net, immigrants are contributors to the public purse, according to analysis by Bloomberg Economics. In some states with a high proportion of low-skilled immigrants, those individuals "often receive more in benefits than they contribute in taxes—though they're still less of a fiscal drain than low-skilled native-born individuals," Bhargavi Sakthivel and Estelle Ou wrote this week. "The overall picture shows that immigrants—particularly high-skilled ones—are net contributors and help reduce the fiscal strain on public resources," they wrote. —Chris Anstey - Read their full analysis on the Bloomberg terminal here.

Bloomberg New Economy: The world faces a wide range of critical challenges, ranging from ongoing military conflict and a worsening climate crisis to the unforeseen consequences of deglobalization and accelerating artificial intelligence. But these challenges are not insurmountable. Join us in Sao Paulo on Oct. 22-23 as leaders in business and government from across the globe come together to discuss the biggest issues of our time and mark the path forward. Click here to register. |

No comments:

Post a Comment