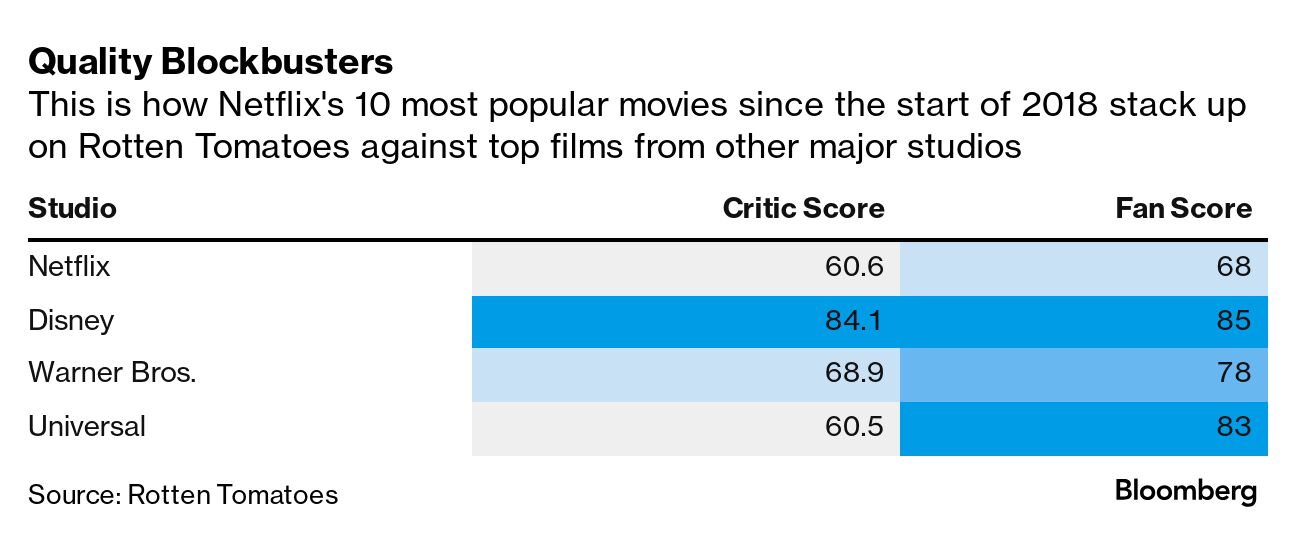

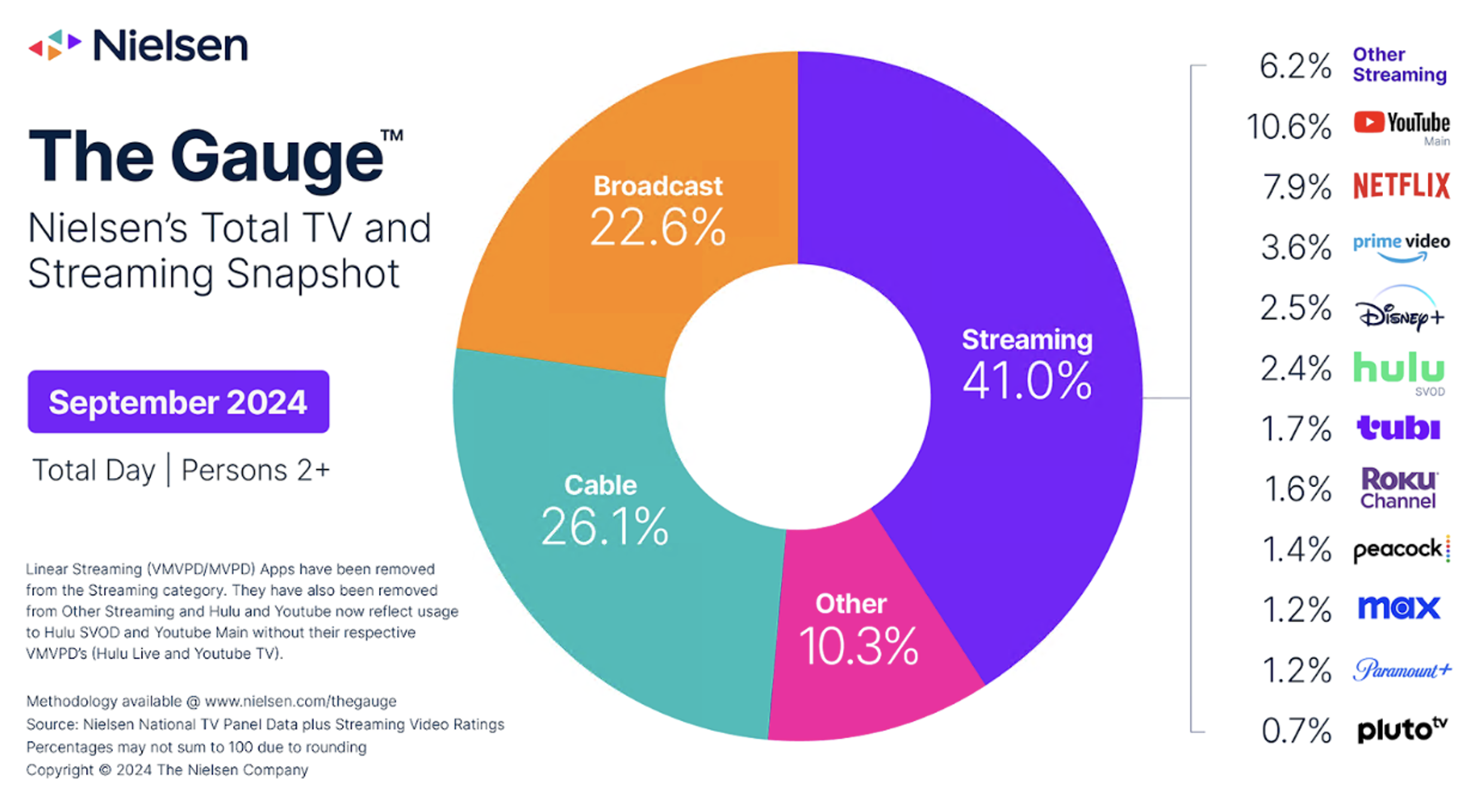

| In the months before Sony planned to release its new animated film Harold and the Purple Crayon, studio executives called their peers at Netflix to see if the streaming service wanted to buy the movie. Sony executives liked the film just fine, but they worried it would fail to break through competing against two other blockbuster animated films, Inside Out 2 and Despicable Me 4, according to people familiar with the matter. In recent years, streaming services have acquired plenty of films that studios no longer wanted to release, from The Cloverfield Paradox to The Trial of the Chicago 7. Most often, the studio wanted to offload a movie it feared would lose money in theaters. Netflix, eager to have studio-produced movies for viewers at home – even if they were cast-offs — would help them get their money back. But Netflix wasn't interested this time, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the talks were confidential. Other studios' leftovers don't fit into the new strategy being developed by Dan Lin, who took over as Netflix's film chairman earlier this year. Lin is eager to reset the public perception of the studio – among viewers and the Hollywood community. Most people in the film business don't think Netflix makes good movies. They also don't believe streamed movies can have the same impact as films released in theaters. There is "no way to have cultural impact without the theatrical experience, just not possible on direct to streaming," producer Jason Blum said at the Screentime conference this month. Netflix hates this narrative. Chief Content Officer Bela Bajaria disputed it at Screentime just hours before Blum went on stage. This past week, Sarandos touted the large audience for Netflix movies during a call with analysts. "What we do for filmmakers is we bring them the biggest audience in the world," Sarandos said. "And then we help them make the best films of their life." Yet Sarandos and Bajaria have acknowledged internally that their films can be better and more cost-effective. Making that dream a reality falls to Lin, a former Warner Bros. executive who has spent the last decade producing films such as The Lego Movie. Restructuring the biggest studio in townLin has told business partners that the push for quality starts with developing more projects in-house and being more selective. Netflix will make fewer movies and prioritize certain genres. It won't overspend just to be in business with big stars. Put less charitably, Lin wants to make better movies by making fewer and spending less. Netflix will still release more original movies than any company in the world, especially when you consider titles from outside the US that don't fall under Lin. His team will release 25 to 30 movies a year, which amounts to a new movie every other week. Most of those will be original ideas and cost less than $100 million. They will span multiple genres, encompassing movies released by a major studio like Warner Bros. and an indie like A24. Once a quarter, the studio will release a tentpole feature like the recent sequel to Beverly Hills Cop or Zack Snyder's Rebel Moon. Lin would like to spend $120 million to $150 million on those titles but will spend more where appropriate. The budget for Greta Gerwig's forthcoming adaptation of The Chronicles of Narnia will almost certainly exceed $200 million. Gerwig also wants a proper theatrical release. Lin has restructured Netflix's film division to execute his strategy, trimming staff and putting executives in charge of specific genres. Ori Marmur oversees action and sci-fi, while Niija Kuykendall handles faith-based projects, as well as holiday and young-adult fare. Kira Goldberg handles dramas and thrillers. Lin also hired a couple of veteran studio executives in Doug Belgrad and Hannah Minghella, both formerly of Sony, to help run the show. Lin made these changes to make it easier to work with Netflix, though his strategy has angered some members of the creative community and frustrated his staff. Telling your employees that their movies sucked doesn't lift morale. Rightsizing budgets and taking fewer big swings doesn't endear you to talent or their representatives, especially when you don't release movies in theaters. The film team went on a retreat last month to a facility near Lake Tahoe and settled on a new mantra — no daylight — to stress the need for cohesion and collaboration. The murmurs of discontent have quieted in the months since Lin took over. Lin has already taken a couple of big swings, securing the next film from director Kathryn Bigelow, the reunion of Michael Bay and Will Smith, as well as a sequel to Happy Gilmore. Some backlash from the Hollywood community was inevitable. Lin's predecessor, Scott Stuber, was an industry fixture who arrived at Netflix with a blank checkbook. He built a studio from scratch and commissioned hundreds of movies, many of them with budgets that exceeded what filmmakers would have received anywhere else. He spent $200 million on action movies like The Grey Man and Red Notice and something similar on Martin Scorsese's The Irishman. He produced more than 50 movies a year, most of which even journalists and cinephiles can't remember. Stuber also tried and ultimately failed to convince his bosses to put their movies in theaters. The consensus – and Stuber would say as much — is that they made too many bad movies. (They also made some really good ones.) Pretty much everyone in Hollywood acknowledges Netflix needed to change its approach. It's hard to sustain quality making a movie a week and it doesn't make a ton of sense to spend $200 million on a movie that won't appear in theaters. Netflix can license those from studios like Sony and Universal. Still, filmmakers, agents and lawyers accustomed to huge paydays don't like adjusting to the new financial reality. The Cameron Diaz corollaryWhether Lin can bring costs under control and improve quality remains to be seen. It's one thing to say you won't overpay for a package or a star, and it's another to actually do it. Stuber didn't want to pay Cameron Diaz $45 million for two movies. But that's what it took to lure her out of "retirement," according to three people familiar with the terms. Netflix may try to get around some of these fees by paying less upfront and dangling the prospect of more money in success. It's only done that on a few projects so far and its executives say this is not a new model. That would be one way to control costs on a sequel to its most-watched film ever, Red Notice, an action comedy starring Ryan Reynolds, Dwayne Johnson and Gal Gadot. The Rock, Reynolds and Gadot earned more than $80 million between them for the first movie, according to two people familiar with their salaries. To make another movie, which has been discussed, the talent alone would cost more than $100 million. Add in the actual cost of making the project, and the budget balloons to $250 million without much effort, said the people, who asked not to be identified discussing salaries. Controlling cost is a little easier on some of the service's awards plays. Rather than spend a reported $80 million to produce Maestro, it spent a fraction of that to acquire Emilia Perez and Maria. The pursuit of quality also begs the questions as to what exactly that means. Red Notice has a score of just 37% from critics on Rotten Tomatoes, but 92% from viewers. The most-watched Netflix movie of the first half of the year was Damsel, a film starring Millie Bobby Brown that has received middling reviews. The biggest movie hit of the second half so far, Rebel Ridge, pleased both viewers and critics. In its pursuit of 1 billion viewers, Netflix wants to have it all. You're getting this a day late because I had an appointment at Dodger Stadium last night. Apologies, but it's a World Series rematch 43 years in the making. The Los Angeles Dodgers and New York Yankees will face each other in the World Series for the first time since 1981 — and the 12th time overall. Executives at Major League Baseball are popping bottles to celebrate. TV ratings for Major League Baseball's playoffs are already way up over a year ago. Viewership increased 18% leading into the most recent round, the league championship series. Now the two best teams from the two biggest markets with the two best players in the world are playing in its biggest event. This should be the most-watched World Series since at least 2016 or 2017, provided it goes at least six games. (The 1981 series averaged 41 million viewers. That seems… unlikely.) While some of the ratings boost is temporary, this isn't just about LA and New York. Rule changes have made baseball faster and more fun for the average viewer. Major stars like Shohei Ohtani have moved to the league's best teams. Baseball, which has been losing cultural relevance for years, finally has a little juice! But football isn't saving broadcastBroadcast and cable viewing declined more than 4% in September from a year ago. Streaming (and other types of entertainment) benefited. A couple other takeaways from The Gauge… - Disney+ continues to gain as Hulu shrinks.

- Amazon had its highest share ever, thanks to football.

- Max and Paramount+ are tied for last among major paid streaming services.

The podcast electionPresidential candidates have finally recognized the power of podcasts and YouTube. Donald Trump has conducted a tour of podcasts hosted by White dudes popular among young White dudes. Kamala Harris has tried to shore up her strengths, appearing on Call Her Daddy (young women) and All The Smoke (Black men). Both candidates have recognized that the traditional media stops — TV stations, newspapers, cable news, magazines — aren't enough. While still powerful, they don't reach as many young, persuadable voters. Ashley Carman has a good piece breaking down why podcasts are so useful to politicians eager to get out the vote. Shows like SmartLess and Call Her Daddy reach as many if not more listeners every week than cable news shows. The No. 1 movie in the world is…Smile 2. The horror sequel grossed $46 million worldwide this weekend. Horror movies have topped the box office two weekends in a row after a choppy start to the year. Deals, deals, dealsI loved wrestling for a few years as a kid and cover the business as an adult. But I still learned a ton about the history of the WWE in Netflix's Mr. McMahon docuseries. I am not sure I learned much about the titular figure. Go Dodgers. |

No comments:

Post a Comment