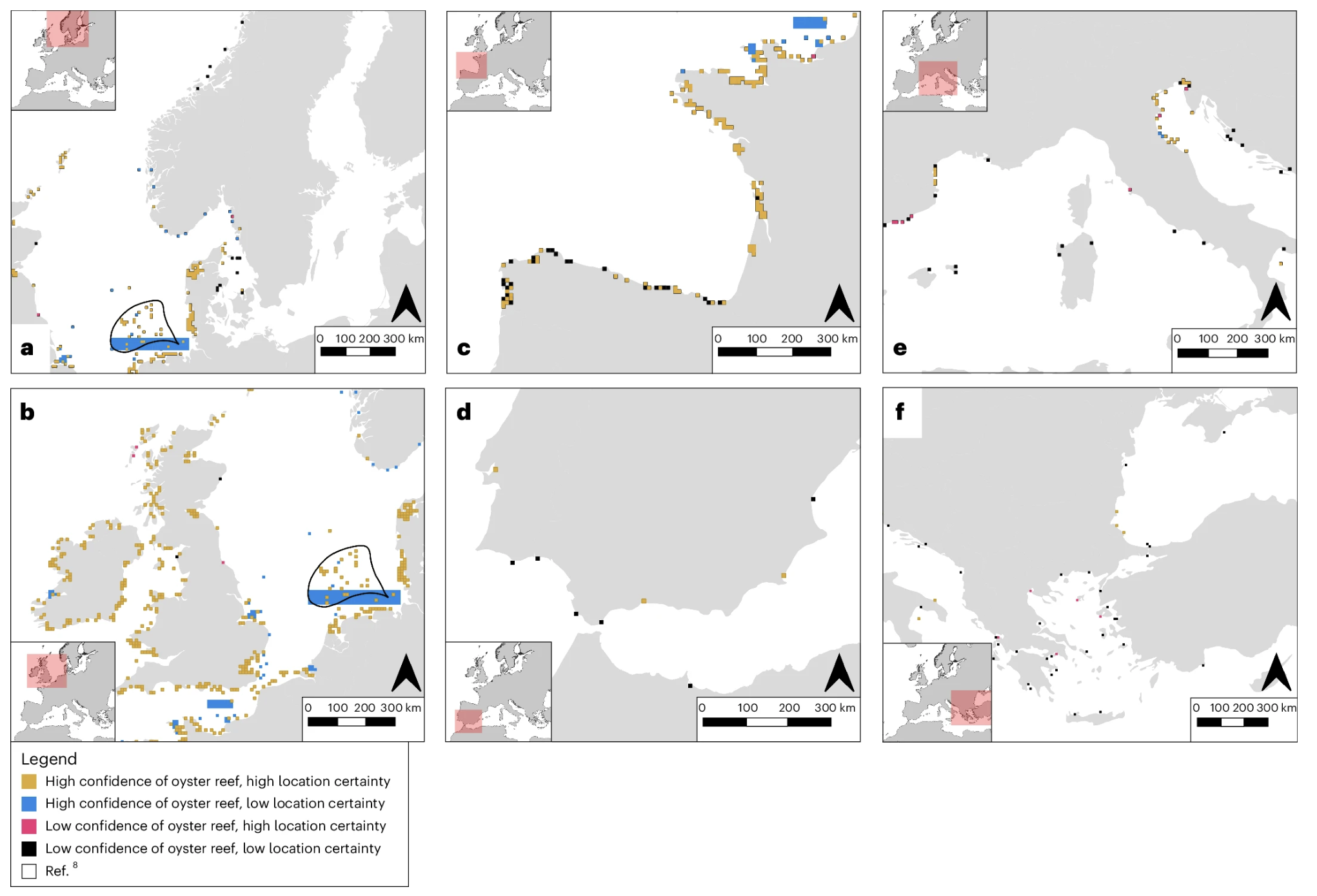

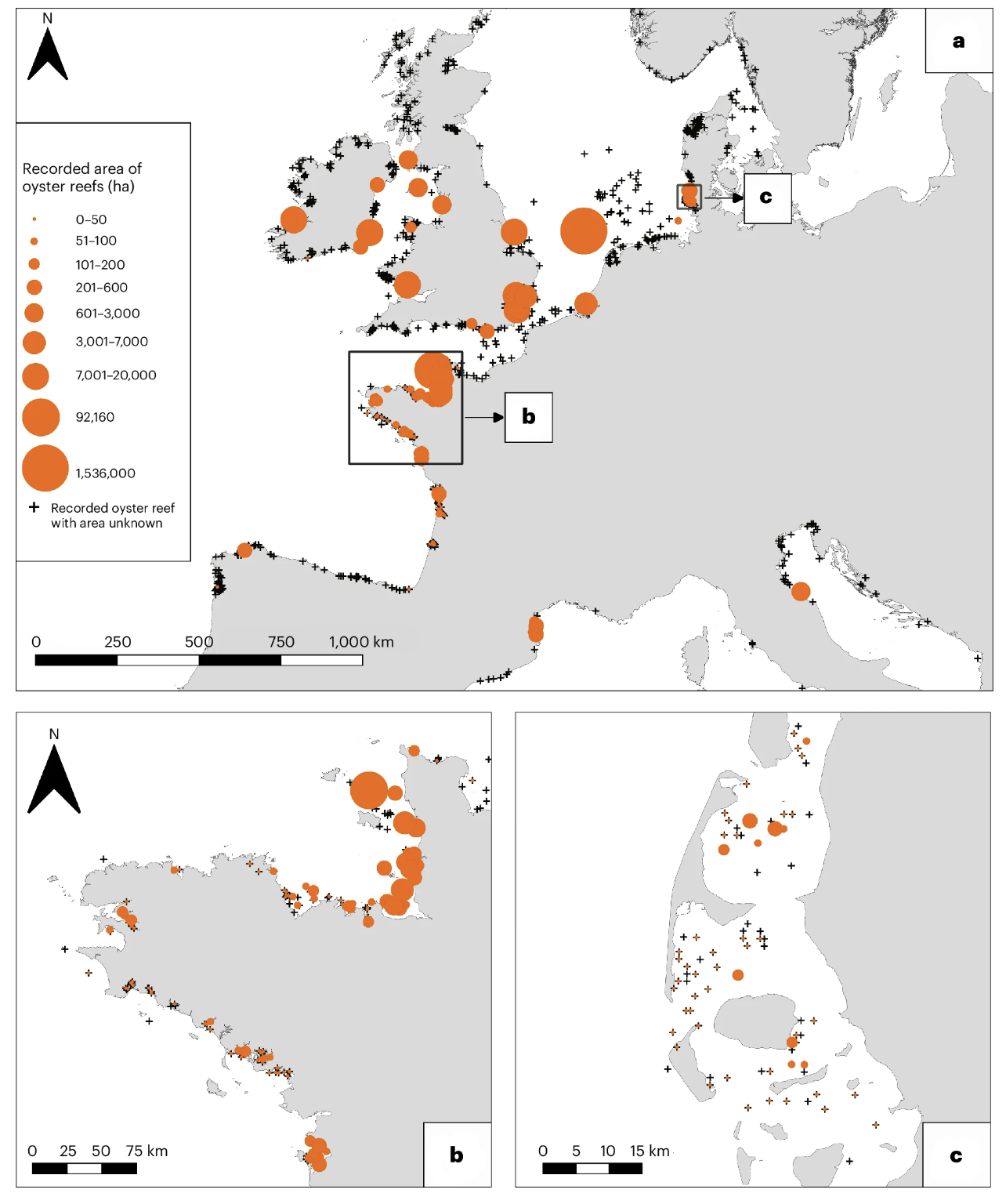

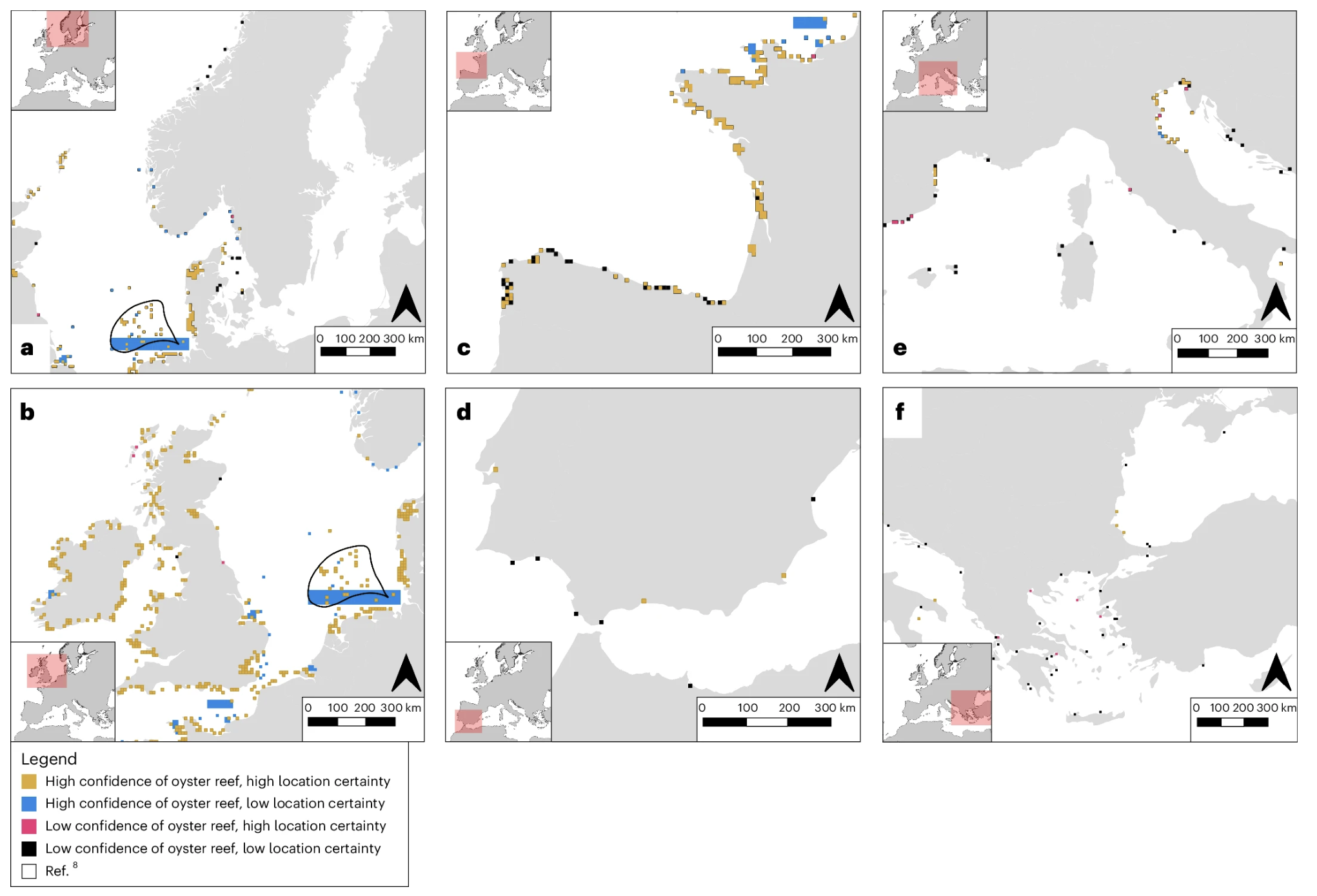

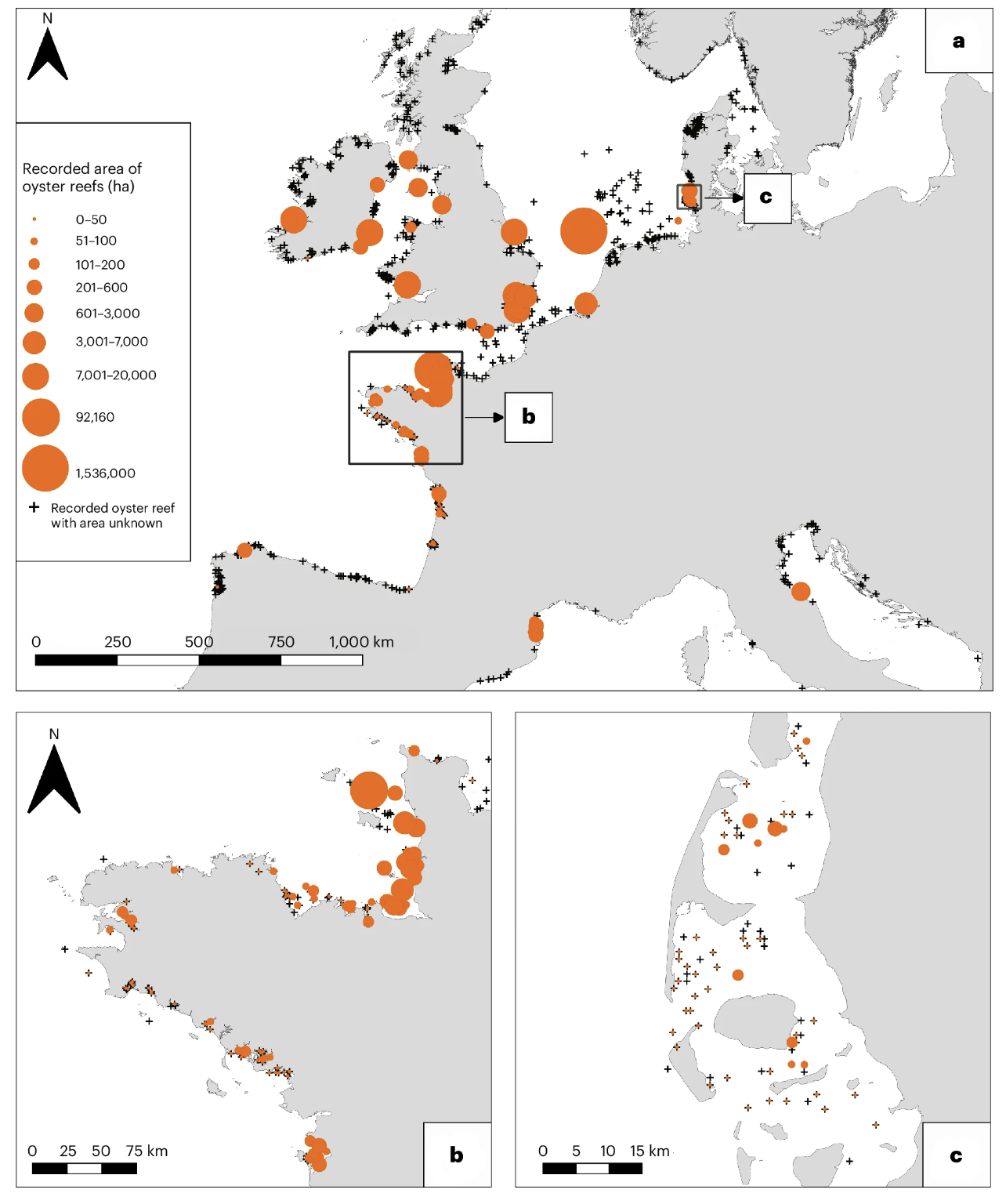

| In the 18th and 19th centuries, wild oysters were so abundant in European oceans that they were a dietary staple for rich and poor people alike. Overfishing and steam-powered dredges put an end to that era, but the importance of oysters wasn't forgotten – not only as a protein-packed food source but also as an environmental asset. Oysters filter out nutrients and pollutants, build habitats for other aquatic species and, in large enough reefs, can act as natural breakwaters. Today, efforts to restore native oyster habitat are underway across Europe. To support that work, a group of scientists attempted to map the historic extent of wild native oysters. Gathering more than 1,600 records published over 350 years that described the presence of oyster habitat in France, Denmark, Ireland, the UK and beyond, they found that prior to the 20th century, oyster reefs covered more than 1.7 million hectares across European oceans. They wrote about their research in a recent paper in Nature Sustainability. Lead study author Ruth Thurstan, a historical ecologist at the University of Exeter, spoke with MapLab editor Laura Bliss about the project. What compelled you to study oysters? We've been influencing our oceans for centuries through activities such as coastal development, fishing and pollution. But because of the inaccessibility of the oceans, we've really only been monitoring populations and habitats for a few years, maybe decades. What we are increasingly discovering through merging historical research and ecological research approaches is that if we don't look further back in time, we are going to miss huge transformations that have occurred, which influences the way we look at what we want to recover, what we want to conserve. What baseline should we be looking at going for? The oyster's quite unique in that it's been economically and culturally important for centuries. We have this historical record, so we thought, why don't we try and turn that into answering questions about our seas more generally. The research involved years of poring through historical archives to gather references to oysters from newspapers, nautical charts, fishery reports and other historical sources, as well as extensive collaboration – there are 38 authors on this paper! Can you describe the research process? Myself and the other co-lead author, Philine Ermgassen, both started looking at this 10 to 15 years ago easily, and we were just collating bits of information. We are part of the Native Oyster Restoration Alliance within Europe, and a few years ago there was this call to understand more about where oyster habitats used to exist for restoration guidance. Through NORA, we connected with folks from multiple other European countries. There were others who, similar to us, have been collecting information over the years.  Locations across Europe where oyster reef presence was assigned from historical sources, identified to 10 square-kilometer grids, with associated confidence levels that reef habitat was present. (Credit: Thurstan, R.H., McCormick, H., Preston, J. et al. Records reveal the vast historical extent of European oyster reef ecosystems. Nat Sustain (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01441-4) What did you find, and how did you translate what you found in those written texts into the maps in this paper? Less than a quarter of the records that we had gave some estimate of spatial extent. And of course these are often in old units that we had to convert. We also had varying resolutions in terms of spatial information. We could go from quite high resolution – people would talk about a particular area that might have been within a bay, or they might even give sort of coordinates. Some of these were old nautical charts, which could be quite highly resolved. The other side of that was sort of out in the open, where you might get a fishing ground that might be quite a few miles in extent each way, or you might just get a vague area. So we had to assign varying levels of uncertainty. In this paper, we had two rather coarse levels which were down to 10 square kilometers. We either had high confidence that the oyster reef occurred in that area and others that was less than that. It really depended on the qualitative description that was associated with the historical source. So for the few had that spatial information, which was several hundred records, the total area that was described was 1.7 million hectares (4.2 million acres, or a little larger than the total landmass of the Hawaiian islands). A lot of that was oyster beds in the North Sea area, and was described as a little bit of a hazard to fishing because there were so many oysters that trawlers would actually avoid those beds until they got better gear that could then run through them, and collect those oysters in large amounts. What's astounding about this is that first of all, that is definitely an underestimate because most of the sources didn't give you spatial information. But also, nothing like that exists today within European seas. The magnitude of that transformation is quite astounding.  Figure A shows the recorded extent (hectares, orange circles) of oyster reefs around Europe. The crosses indicate records of reefs of unknown areal extent. Figure B shows the coast of France. Figure C shows the Wadden Sea. (Credit: Thurstan, R.H., McCormick, H., Preston, J. et al. Records reveal the vast historical extent of European oyster reef ecosystems. Nat Sustain (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01441-4) There are oyster reef restoration efforts underway globally. Is it even possible to get anywhere near what these historical levels were, given changing ocean temperatures, new diseases, the extent of aquaculture and all these things that have contributed to the change? We would have to really ramp up our restoration efforts and be thinking at seascape scales. At this point in time, in terms of the European native oyster, there are over 30 restoration efforts around Europe, but they're all very small scale, mostly less than a hectare. So they're really at that early phase of finding out what is achievable and, and from there the hope is that they will scale up. I think the importance of this study is that before people weren't thinking like that because they didn't know what used to be there. Just helping to raise ambitions for restoration and conservation is hugely important, because if people before didn't imagine that reefs existed, then they were never going to try and get reefs back. -

Nowhere in America is safe from climate-fueled storms and fires (Bloomberg News) -

Federal flood maps are no match for Florida's double hurricane (Bloomberg News) -

When a television meteorologist breaks down on air and admits fear (New York Times) -

How to find emergency shelters using Google Maps (Android Headlines) -

Gaza Strip in maps: How a year of war has drastically changed life in the territory (BBC) |

No comments:

Post a Comment