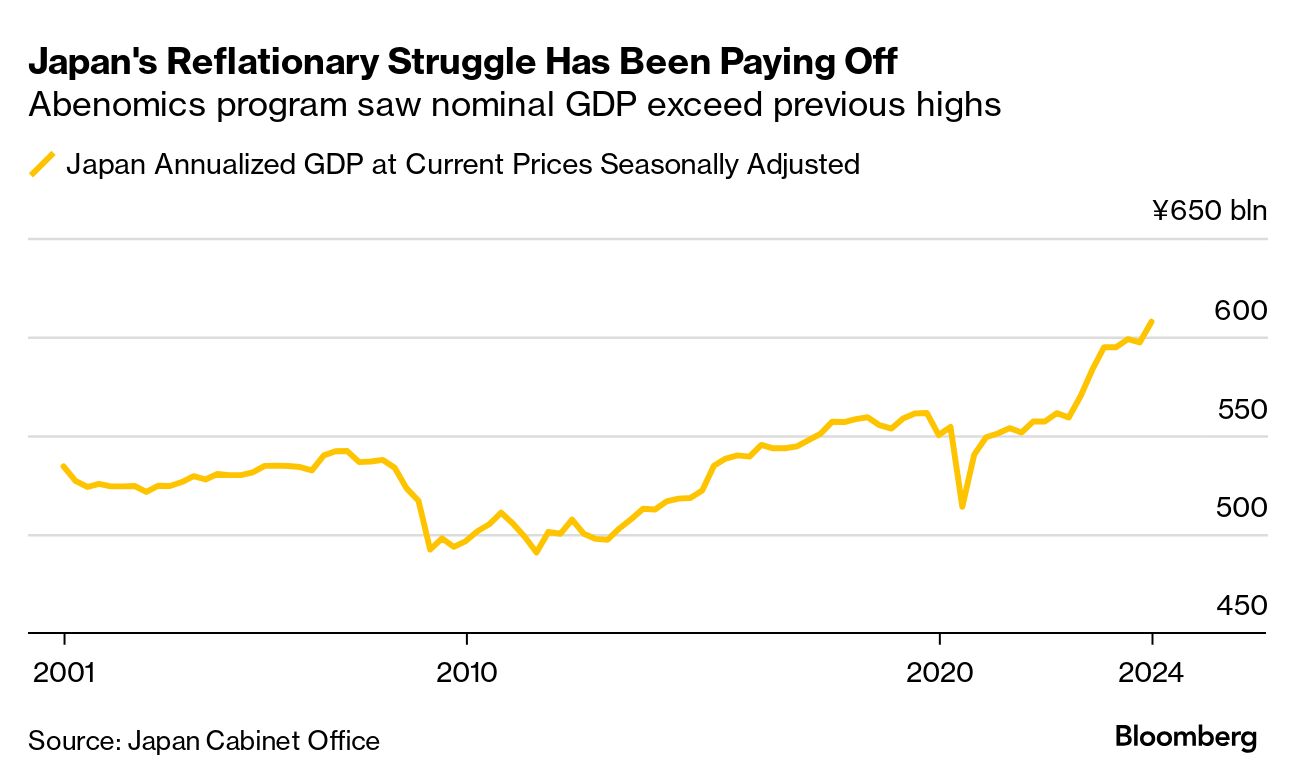

| I'm Chris Anstey, an economics editor in Boston. Today we're looking at concerns about Japan's economic direction. Send us feedback and tips to ecodaily@bloomberg.net or get in touch on X via @economics. And if you aren't yet signed up to receive this newsletter, you can do so here. Since the turn of the century, Japan's economy has repeatedly seen hopes for its revival rise, only to be dashed. With the nation's latest switch in prime minister, that fear has again emerged. In the early 2000s, the Koizumi administration finally fixed the nation's financial sector, and GDP gains were picking up steam. Then the global financial crisis hit. The nation's industrial output still hasn't recovered from that devastating downturn. With Shinzo Abe's reflationary "Abenomics" program, the economy again was on the rise in 2013 before an ill-timed sales-tax increase blunted the trajectory in 2014. Still, some of the late Abe's reforms, including an overhaul of corporate governance, have now been bearing fruit. Businesses are paying more attention to shareholder value and deploying cash rather than sitting on it. Abe also consistently lobbied for sustained wage gains, and — spurred ahead by the big burst of post-Covid inflation — that's finally happening. Base pay rose the most since 1993 after this spring's annual negotiations. With stocks soaring to new highs, the narrative had recently emerged that Japan, as Abe once claimed, "is back." Legendary investor Warren Buffett added to the vibe by putting money in Japan's trading companies. But with the Japanese ruling party's latest leadership turnover, Abe's longtime rival, Shigeru Ishiba, has become prime minister. That's stoked concerns about a potential return to fiscal austerity. Ishiba has in the past favored raising corporate and capital gains taxes, and advocates efforts to revive Japan's more rural areas, where the population is sliding. When he unsuccessfully challenged Abe in 2018, he pledged to keep fiscal consolidation in mind. That's in part why Japan's Nikkei 225 stock average tumbled almost 5% Monday, in the wake of Ishiba's selection. "We don't expect Ishiba to choke off the recovery with tight policies," said Taro Kimura at Bloomberg Economics. "At the margins, though, he could set macro policies on a marginally tighter path." Morgan Stanley's Takeshi Yamaguchi and Masayuki Inui agreed that "market fears about fiscal tightening may be overdone." But the concerns "linger," they wrote in a recent note. Bloomberg Opinion's Gearoid Reidy says the main trouble is that, after having long assailed Abenomics, Ishiba lacks a coherent plan of his own. Japan now turns to a parliamentary election this month, with a supplementary budget expected later in the year. The onus will be on the new prime minister to lay out a platform that sustains Japan's hard-won reflation progress. For more of Reidy's analysis on Japan click here on the Bloomberg terminal. - The White House and Donald Trump lined up behind dockworkers, each accusing the ocean carriers of exploiting employees during the pandemic.

- France is planning around €60 billion in spending cuts and tax hikes in 2025 as the new premier seeks to claw back a widening budget deficit.

- Chinese homebuyers could be seen scouting showrooms at midnight after the country's top cities further relaxed restrictions for homebuying.

- South Korea's inflation slowed more abruptly than expected, while Kenya's price growth eased to the slowest pace in almost 12 years.

- Executives in Brazil are redrawing plans as rates climb. Meanwhile, Moody's raised the country to the cusp of investment grade.

- The Reserve Bank of Australia is facing questions over its practice of holding off-the-record briefings with market participants.

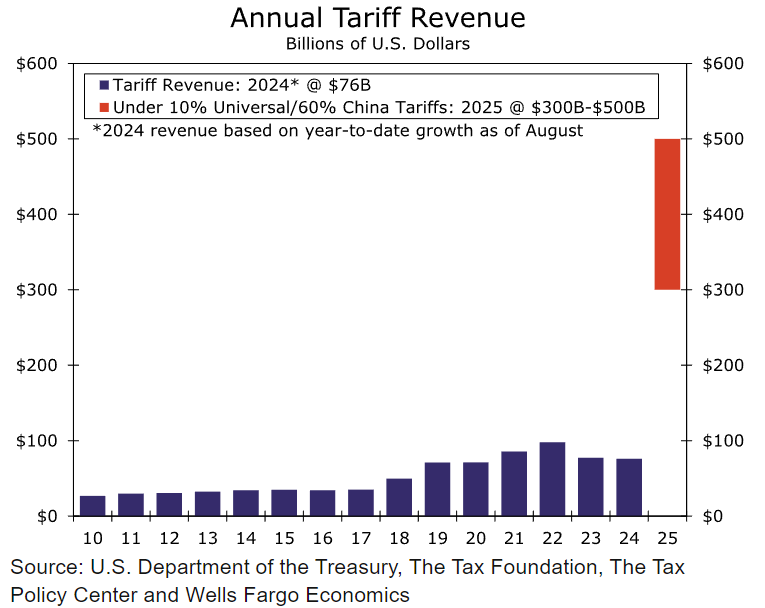

Tariffs haven't been a large part of US government revenues for quite some time, but if Donald Trump wins the election and follows through on a 10% duty on all imports of foreign products and a 60% tariff on Chinese goods, that would change. Wells Fargo economists estimate the government would have collected more than $500 billion last year with those tariffs. "Of course, tariffs along these lines would cause imports into the United States to shrink, particularly from China," so that figure represents more of an upper-bound than a base case," Wells Fargo economists including Michael Pugliese wrote in a note Tuesday. Still, the rates would likely mean "hundreds of billions of dollars annually," they wrote. Bloomberg New Economy: The world faces a wide range of critical challenges, ranging from ongoing military conflict and a worsening climate crisis to the unforeseen consequences of deglobalization and accelerating artificial intelligence. But these challenges are not insurmountable. Join us in Sao Paulo on Oct. 22-23 as leaders in business and government from across the globe come together to discuss the biggest issues of our time and mark the path forward. Click here to register. |

No comments:

Post a Comment