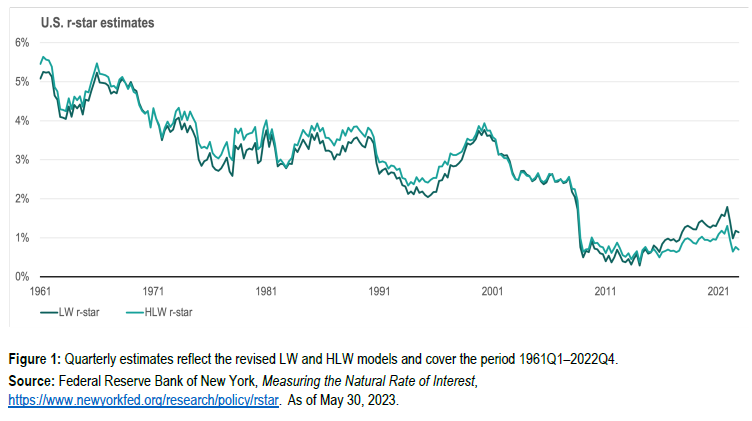

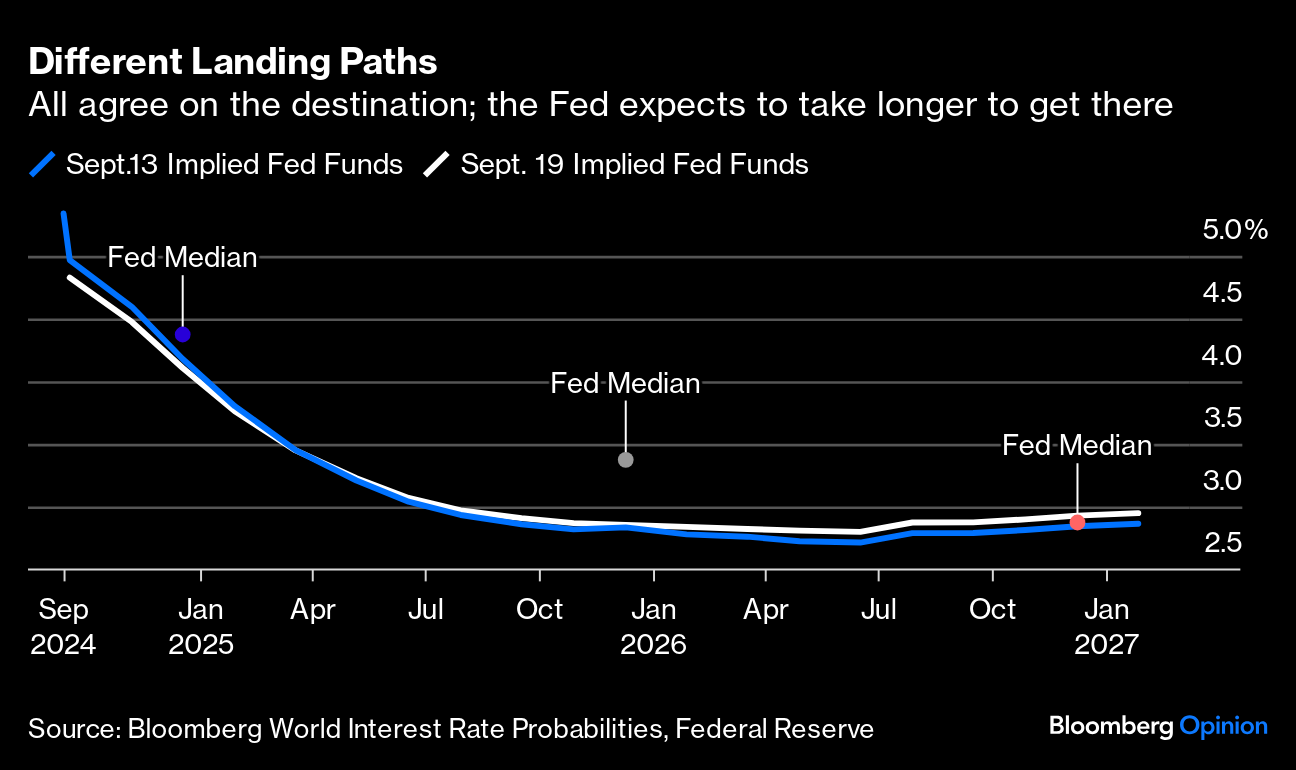

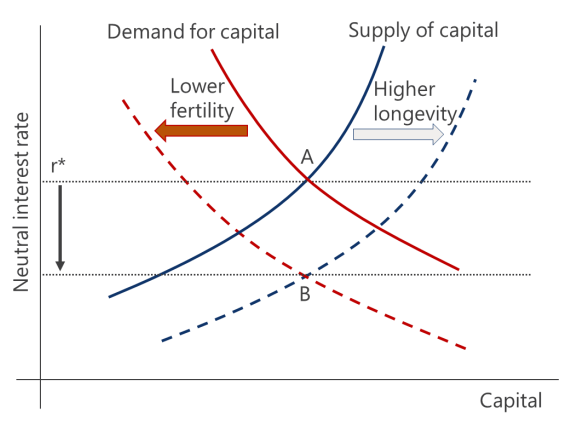

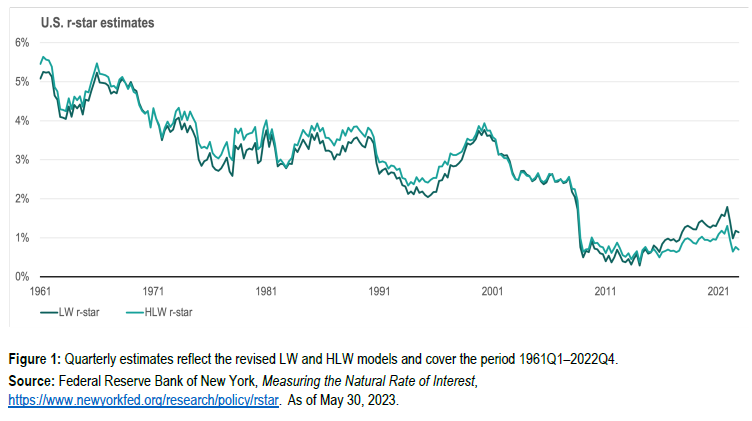

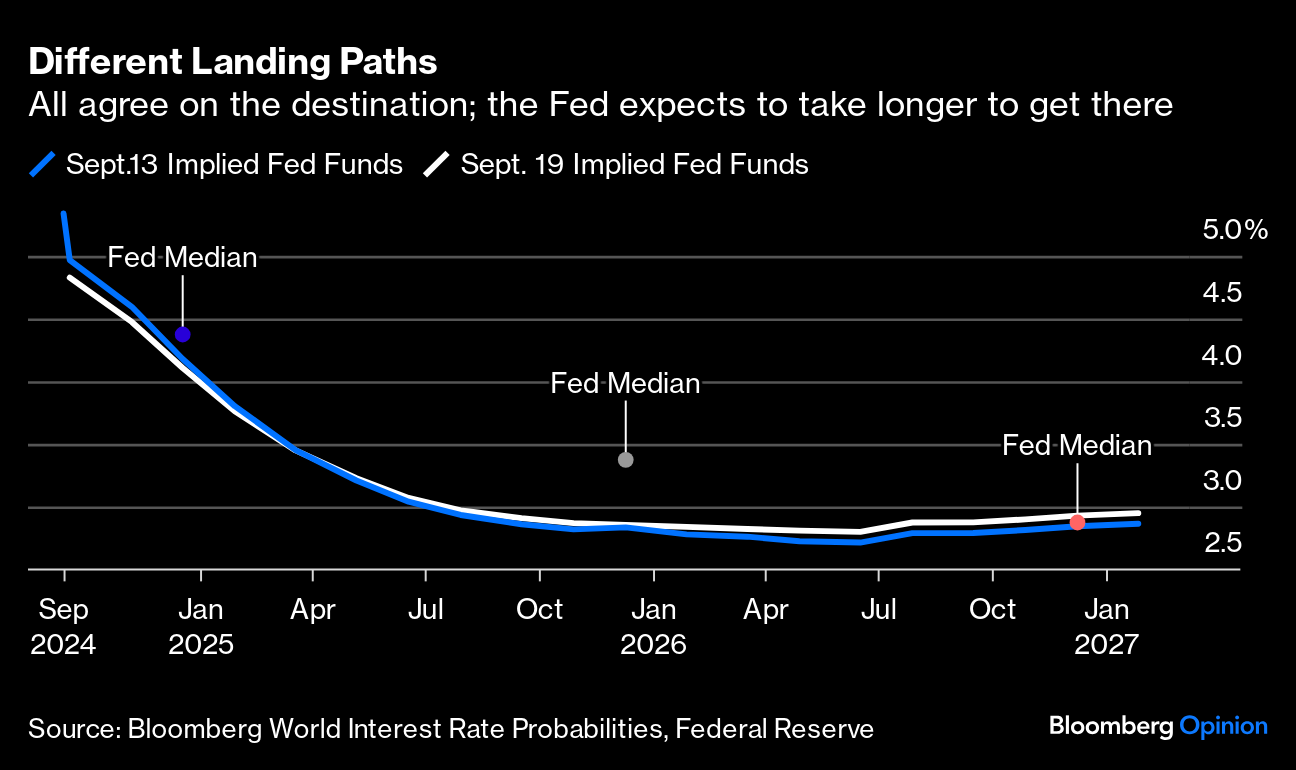

| The last few days have been an exercise in game theory. What were the main motivations for the Federal Reserve, and would that prompt them toward a cut of 0.25% or 0.5% in the fed funds rate? We have our answer, and after a brief pause for contemplation, investors have taken stock markets to fresh records. The S&P 500 closed Thursday at its first all-time high in two months; the summer swoon is firmly in the past. With that excitement now resolved, a much tougher question will come to dominate — what is the neutral real rate of interest, or R* or R-star as economists like to call it? R* will be higher for some economies than others, and it can move (slowly) over time. It signifies the level of interest rates at which monetary policy neither stimulates nor constricts economic growth, and so central bankers should logically hope to keep rates at about that level most of the time. Most annoyingly, it's one of those financial concepts, like the equity risk premium, that exists but is unknowable in real time. It's a product of several long-term factors that affect the demand and supply of capital. Higher productivity will raise the neutral rate, as the economy can grow faster without overheating. Rising inflation expectations will also tend to raise it. Conceptually, the neutral rate shifts with demographics. Higher longevity will mean that people save for longer, and supply capital in the process — which will tend to reduce rates. Lower fertility means less demand for mortgages and the like, or lower demand for capital. That's illustrated in this useful schema from Oxford Economics: Demographics on their own have ensured a decline in R*, as has disappointing productivity growth. The Global Financial Crisis administered a massive further blow downward. A number of estimates are out there. Vanguard Group's chief economist Joe Davis shows how two models from the New York Fed have measured the neutral rate going back to 1960:  There's room for argument over whether rates should have stayed as low as they did for so long after the GFC, but the basic point that the crisis pushed down the neutral rate is hard to contest. Is it safe to assume that it will stay this low? That now looms as the crucial point of disagreement over the future course of the fed funds rate — and by implication for most other building blocks of the financial system, including the valuation of stocks. Using the latest predictions from the futures market, as generated on the Bloomberg Terminal's World Interest Rate Probabilities function, and the latest median projections from the Federal Open Market Committee's dot plot, we find a startling degree of unanimity from now until 2027:  The dots imply that the Fed expects to move more steadily and slowly than the market expects, but everyone agrees on the direction, and on the destination at a little below 3%. The market thinks it will be reached about a year earlier than the Fed does, but that's the extent of the disagreement. After the binary uncertainty of the last week, this is quite a relief. However, the use of the median can create a false sense of consensus. These are the dots showing where each Fed governor expects the rate to be at the end of 2026, 2027 and for the "long term" (which is more or less a synonym for where they think the neutral rate is): There's a spread of 1.75 percentage points within the FOMC, and no single option for the long-term rate gets the vote of more than three members. As the target for inflation is 2%, then this implies R* is 1.75%, as the most hawkish member thinks the long-term fed funds rate should be 3.75%. If that's right, then only four cuts of 25 basis points are needed to get there from the current rate of 4.8%. That destination would likely be reached next year. If the most dovish member is right, another six cuts will be needed to get to a long term rate of 2.25%, implying R* is barely above zero. Anatole Kaletsky, a founder of Gavekal Research, argues: The high end of this range is likely to be proved right. The Fed's neutral rate estimate of 2.9% effectively assumes that the historically unprecedented low interest rates of the post-2008 crisis period were not a temporary aberration, but a permanent "new normal" that will again become the equilibrium state of the world economy in the years and decades ahead. This seems unlikely, considering that the deleveraging that followed the GFC is over, that US companies and households now have historically strong balance sheets and, most importantly, that long-term changes in the capital intensiveness of industry, in geopolitics, in fiscal policy and in demographics are all moving the global economy away from excess savings and secular stagnation toward higher investment and lower savings.

This doesn't just affect how far the Fed has to cut. It also affects the perceived urgency of getting on with monetary easing. If the neutral interest rate is higher than thought, it would help to explain why protracted higher rates haven't slowed down the economy as expected; they're not as restrictive as the Fed or many others believe.  R-star power. Photographer: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg That's a key argument made by Vanguard's Davis earlier this year in a paper arguing that R* is about 1.5%, rather than the 0.5% implied by the dot plot, and that therefore policy isn't as restrictive as the Fed thinks. Further, this isn't just about the steady easing of the pandemic shock: The rise of r-star began before the onset of Covid and reflects changes in secular drivers that are unlikely to quickly reverse. This strongly suggests that the "new normal" era of secularly low rates is already over, and perhaps an era of "sound money" has begun.

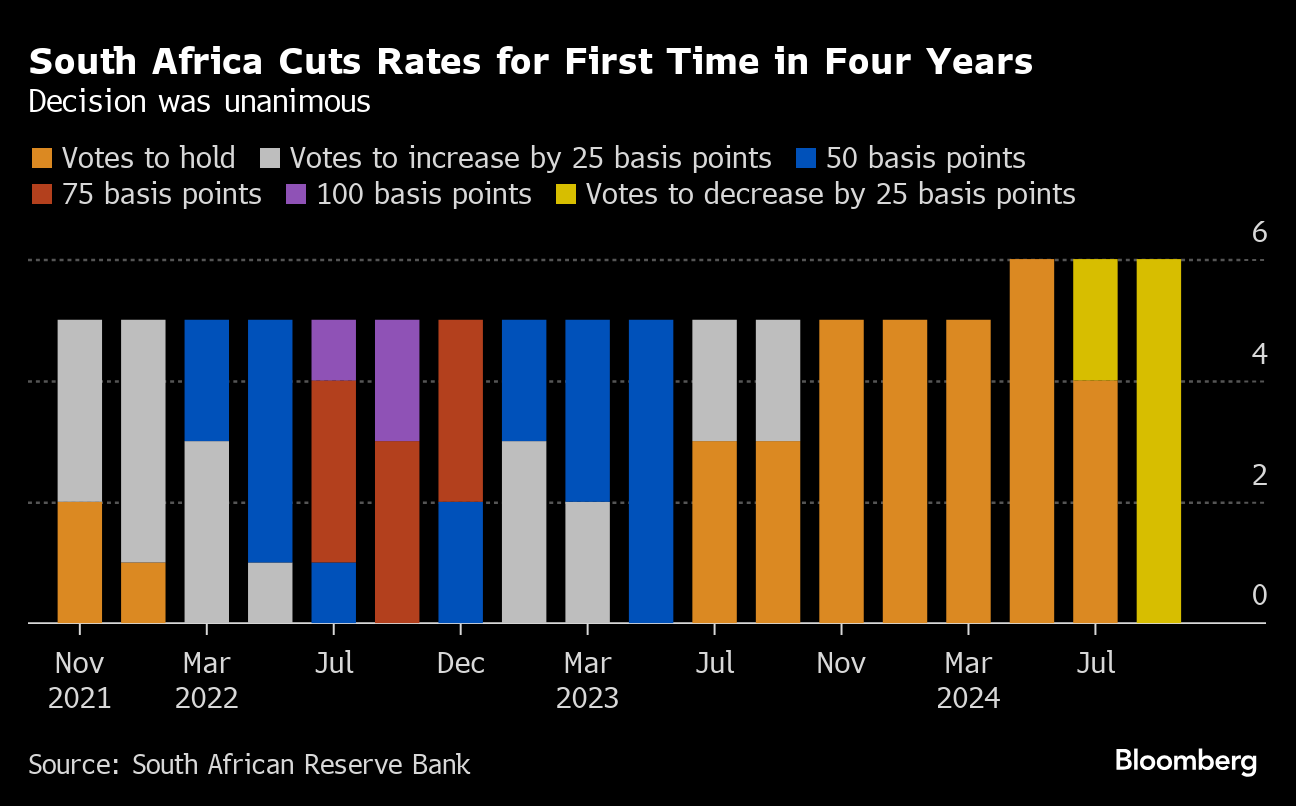

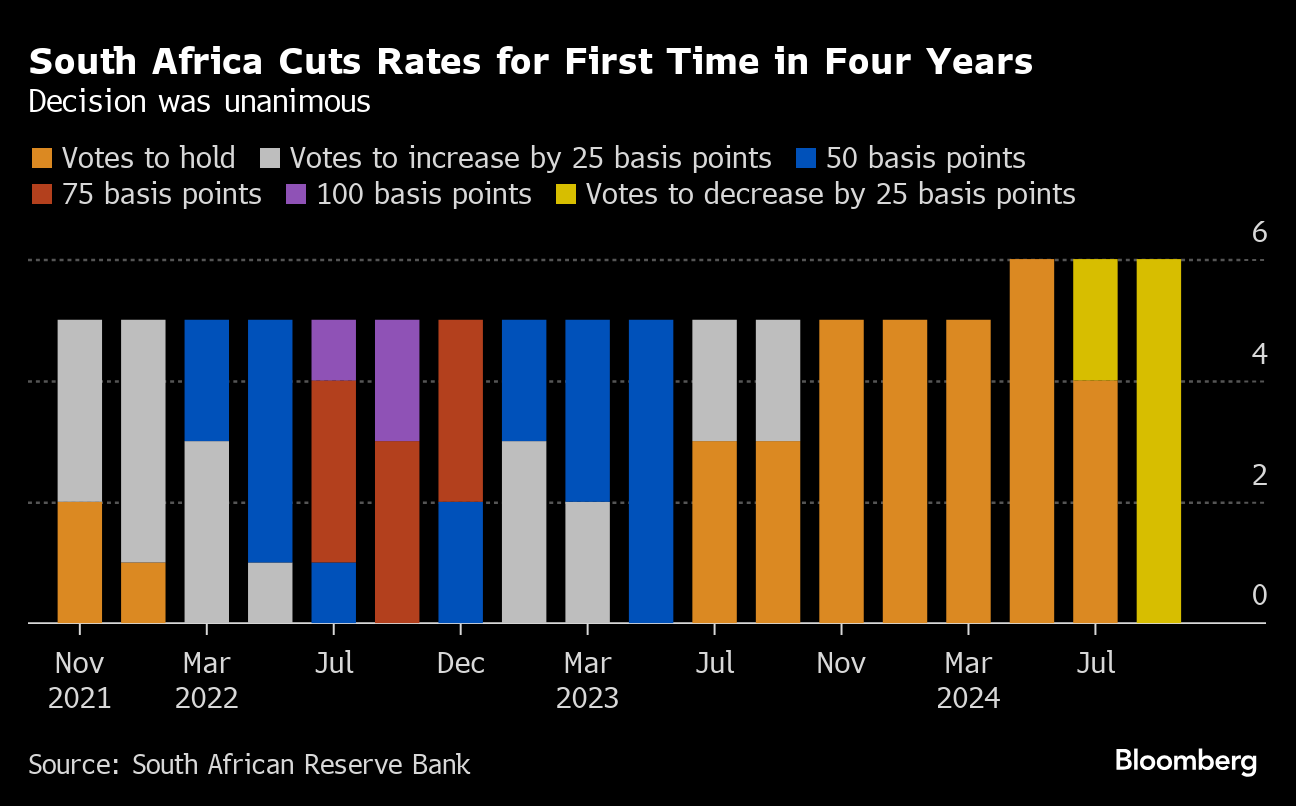

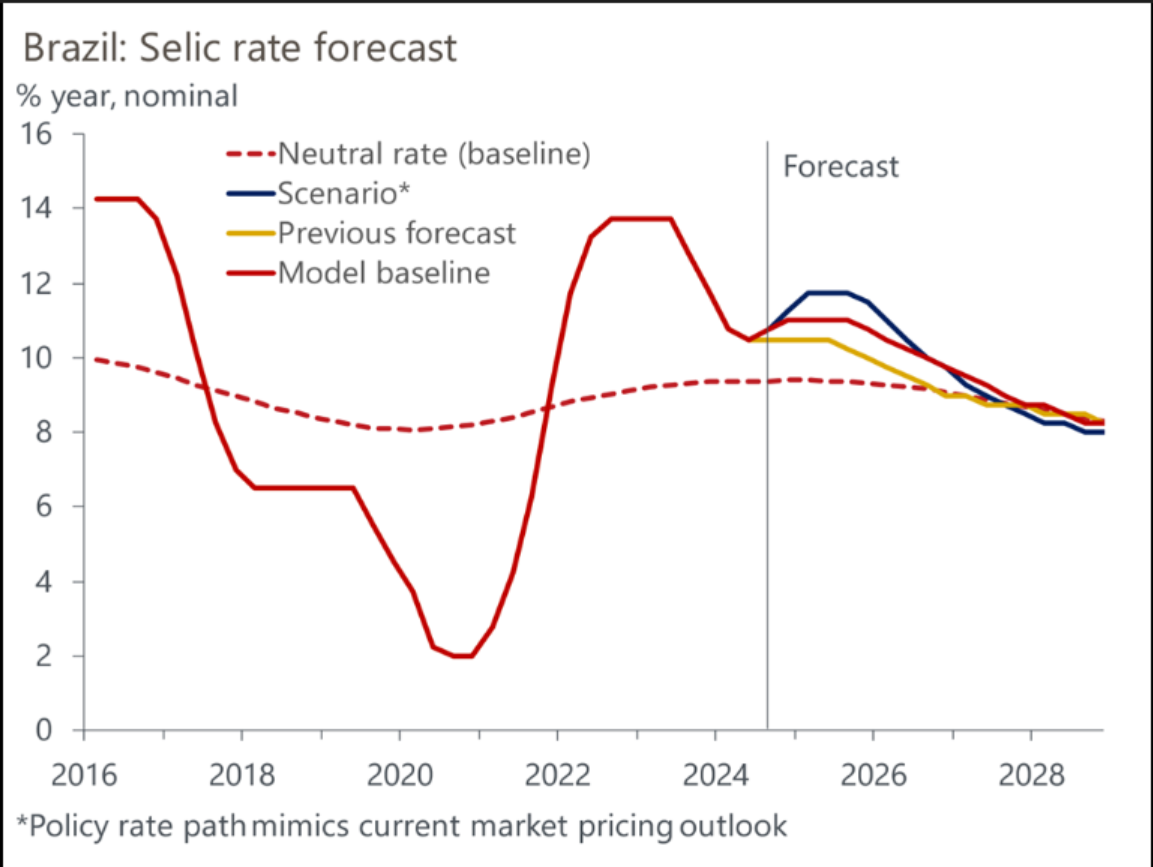

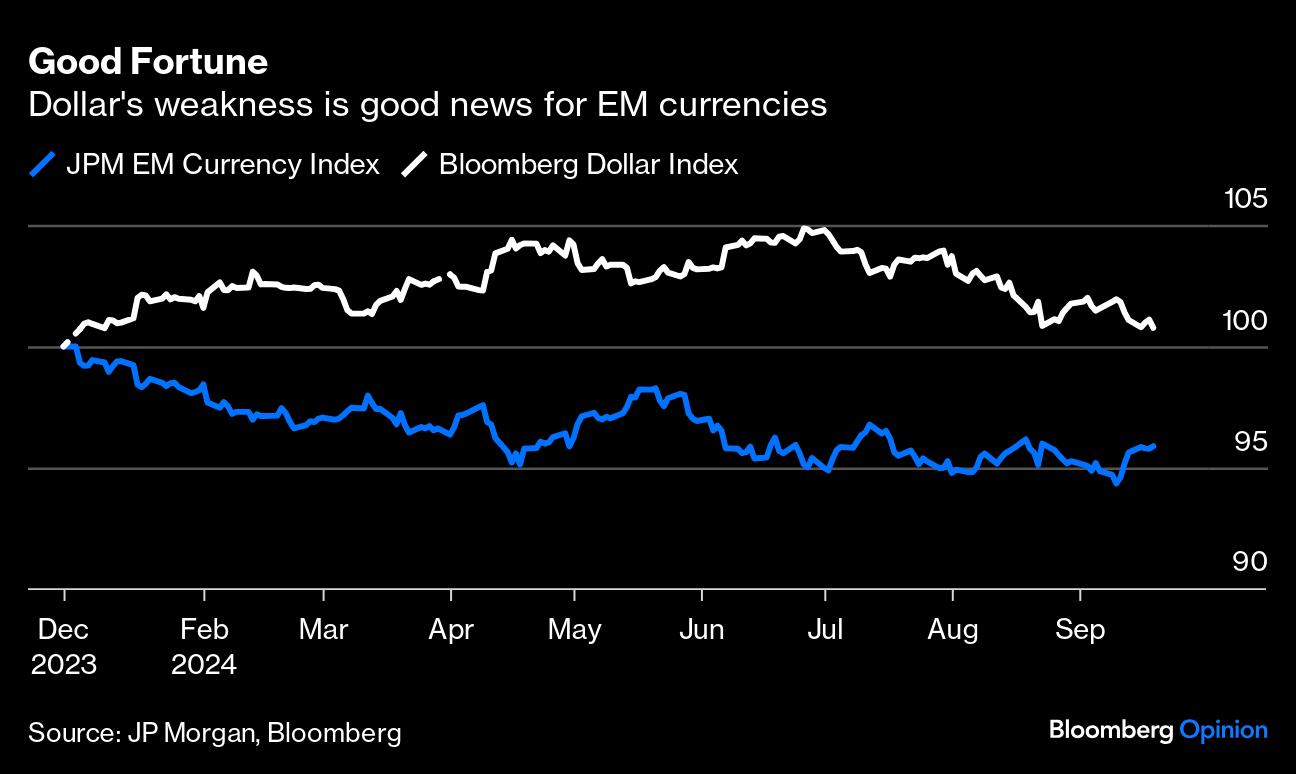

Put differently, we are so preoccupied by the pandemic shock that we may be missing that the even greater GFC shock is also very slowly being resolved. There's an election to deal with in the US, and neutral rates vary between different countries. But the level of the natural rate is now the critical known unknown facing the economy and the financial system. We'd all better get used to it. Meanwhile, central bankers in emerging markets can be forgiven for feeling unalloyed relief after the Fed's jumbo cut. Developing countries have already reaped the benefits from proactively dealing with the post-pandemic inflation breakout, but subsequent easing has been constrained by high rates elsewhere. Aggressive cuts that aren't on the same wavelength with developed central banks are imprudent for emerging markets that have to deal with weak and potentially volatile currencies. The Fed has just lightened their burden and made it easier for them to countenance monetary easing. Right on cue, South Africa has cut its lending rates by 25 basis points — its first since the pandemic. The Rainbow Nation's easing cycle wasn't driven solely by developments elsewhere. Inflation in Africa's largest economy had cooled off notably, with August's 4.4% print marking the first time since the surge began that price rises have slipped below the midpoint of the central bank's 3% to 6% target. The magnitude of the US cut erases any lingering apprehensions for emerging banks, and helps to explain how — in another post-pandemic first — the South African decision was unanimous:  But it's not as though the Fed sets the direction for everybody. Different economies are beginning to diverge as the Covid shock slips further into the past. Across the Atlantic, Brazil's central bank took rates in the opposite direction. The decision to hike its Selic rate by 25 basis points to 10.75% was unanimous. The pace of price increases was drifting from the Central Bank of Brasil's comfort zone and policymakers had to do something. Oxford Economics' Felipe Camargo suggests that desire to regain credibility on its inflation-targeting mandate may force the central bank to stray from an optimal monetary policy. Put differently, international investors still don't give economies like Brazil the benefit of the doubt, and that can compel uncomfortable policy decisions. Politics, and particularly international capital's distrust of populist politicians, colored the decision. After several attacks led by President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva attempting to force looser monetary policy, analysts at Capital Economics viewed Wednesday's decision as an attempt to shore up the central bank's credibility. It will take time and some painful decisions. However, there's consensus that this hiking cycle will be fairly contained, although there's uncertainty on the pace and magnitude. Camargo notes that keeping rates near 11% should be enough to push inflation back to target before the end of Lula's mandate in 2026. "Hiking beyond this would risk pushing the central bank into a U-turn that would force it to cut rates aggressively, as it rushed behind the curve to fix a policy mistake." This Oxford Economics chart shows what it would take to tame inflation: The silver lining in the decision is to bolster Brazil's currency at a time when the dollar is losing ground. The real has gained almost 6% over the dollar since Aug. 1. The South African rand is also strengthening at the greenback's expense, gaining more than 2.4% in the last week alone. Overall, the Fed's easing cycle risks piling pressure on the dollar, which has been on a downward trend for the last two years. A weak dollar is invariably good news for emerging markets, as shown in this comparison with a basket of emerging market currencies: The Fed's pivot should be a boon for emerging markets, and particularly their currencies. Citibank analysts argue that investors will likely look to build up positions in higher interest rate jurisdictions that are more linked to US monetary policy. Latin American currencies might begin to look a lot more appealing to American dollar-based investors. Emerging markets have been given a great opening; let's hope they make the most of it.

—Richard Abbey OK, more stars. While pondering R*, you could try listening to She's a Star by James, Star by Kiki Dee, Lucky Star by Madonna, Shining Star by Earth Wind and Fire, Star Star by the Rolling Stones, Ziggy Stardust and Starman by David Bowie, Jesus Christ Superstar, Champagne Supernova by Oasis, Shooting Star by Dollar, Starship Trooper by Sarah Brightman, Another Star by Stevie Wonder, Jane by Jefferson Starship, I'm in Love With a German Film Star by The Passions (or Foo Fighters), or When the Stars Go Blue by The Corrs. I'm sure there are many more out there, aren't there? And on the subject of truly galactic stars, happy 90th birthday to Sophia Loren. Have a great weekend everyone.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment