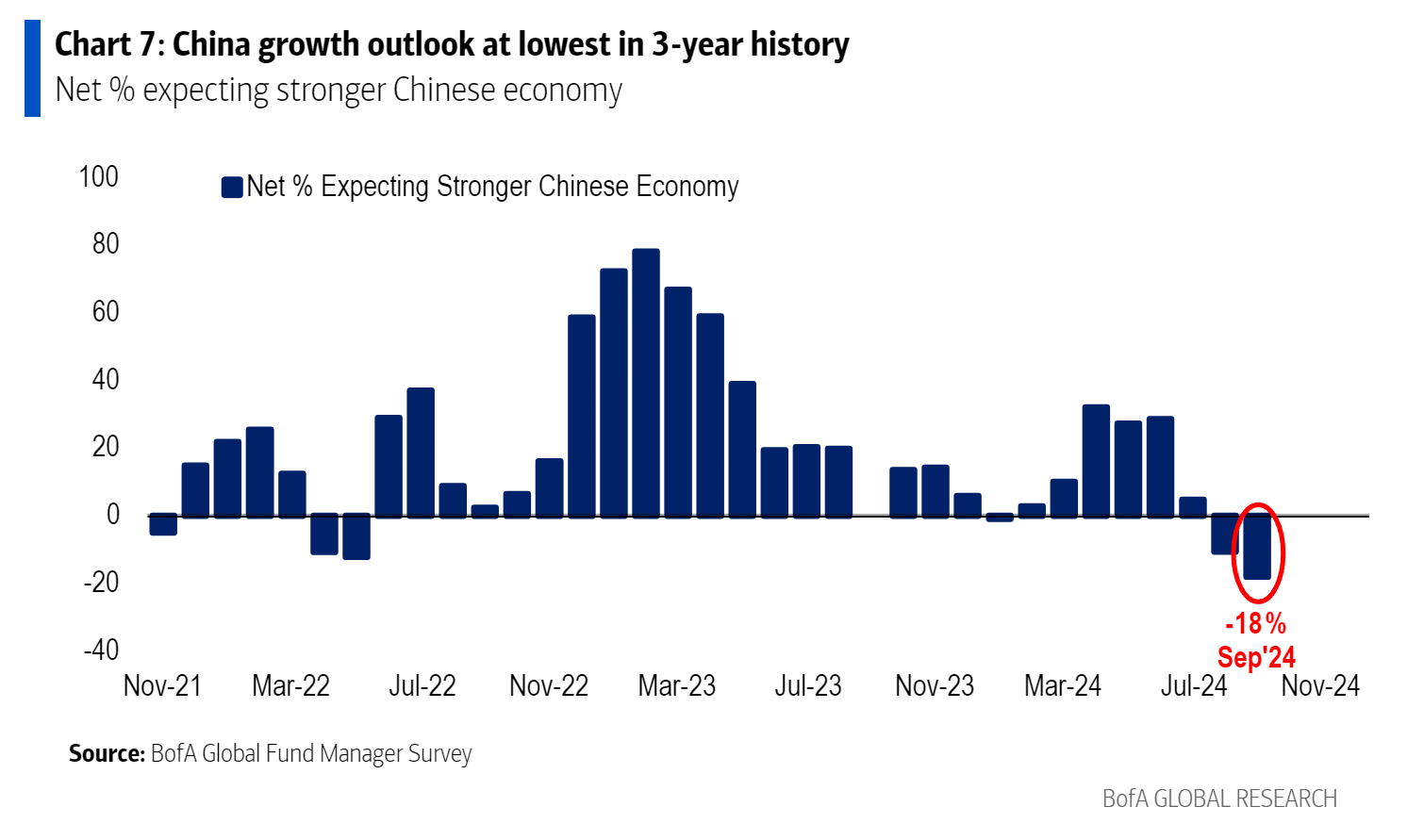

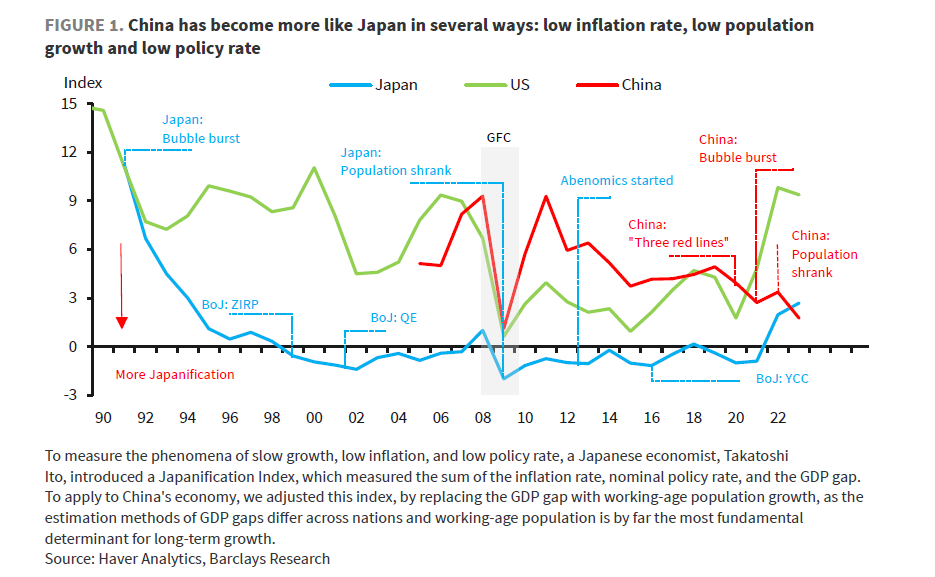

| As everyone waits news from the Federal Reserve, eyes should turn toward China. Beijing's sputtering growth is drawing comparison to Japan's classic slump since the 1990s — Japanification. That showed in Bank of America's latest Global Fund Manager Survey, which found growth expectations for China at a record low, with a net 18% expecting a weaker Chinese economy: China now has all the symptoms of a "balance-sheet recession": a protracted period of deflation, property market declines, and a debt overhang. And, just as in Japan, this has followed an amazing period of growth. What would it take to escape the quagmire? Barclays Plc researchers argue that China faces a unique set of challenges, which in some instances make it worse off than Japan — population decline, housing troubles, an even more pronounced slump. Barclays highlights the resemblances: The housing sector's interconnectedness with global demand for commodities such as steel and other raw materials means the problems aren't Beijing's alone. Indeed, the Institute of International Monetary Research's Tim Congdon believes resolving the Chinese financial system's difficulties to be vital for global economic prospects. Policymakers announced reforms in May to bolster the property sector, which appear to be showing some signs of delivering an improvement. Overstretched household balance sheets could be thwarting a bigger turnaround. Household debt has more than doubled in the past decade, reaching 143% of disposable income in 2021 before stabilizing. As such, record low interest rates don't matter; without earning enough, a household's ability to borrow is limited. Longview Economics' Harry Colvin suggests monetary policy has to do more: Looser monetary policy, of course, is unhelpful in a balance-sheet recession… In the near term, given that policy is failing (and too tight), the deterioration in the credit cycle, housing market, and broader economy should persist, particularly in the absence of significant policy easing.

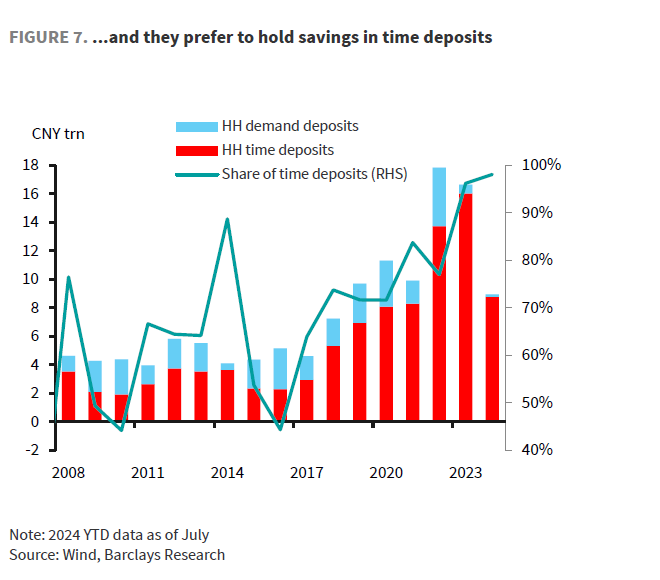

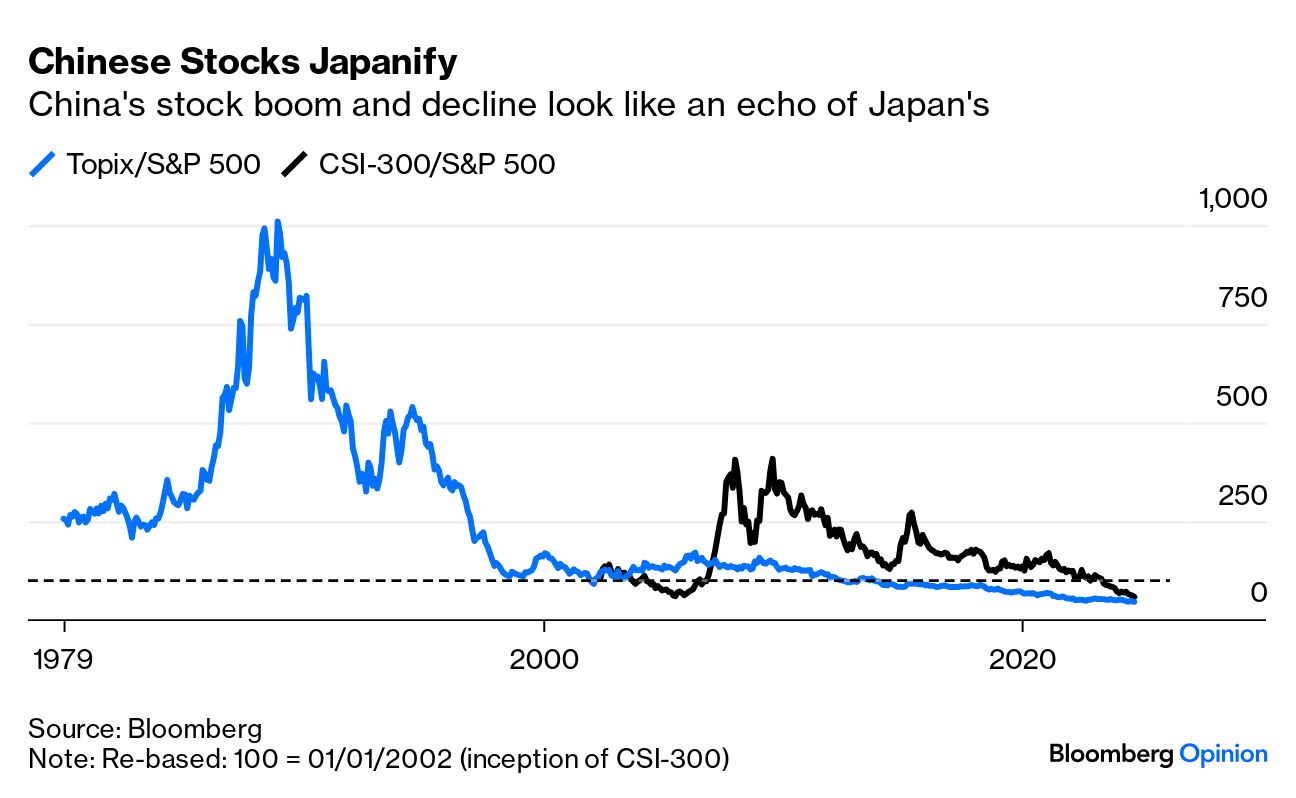

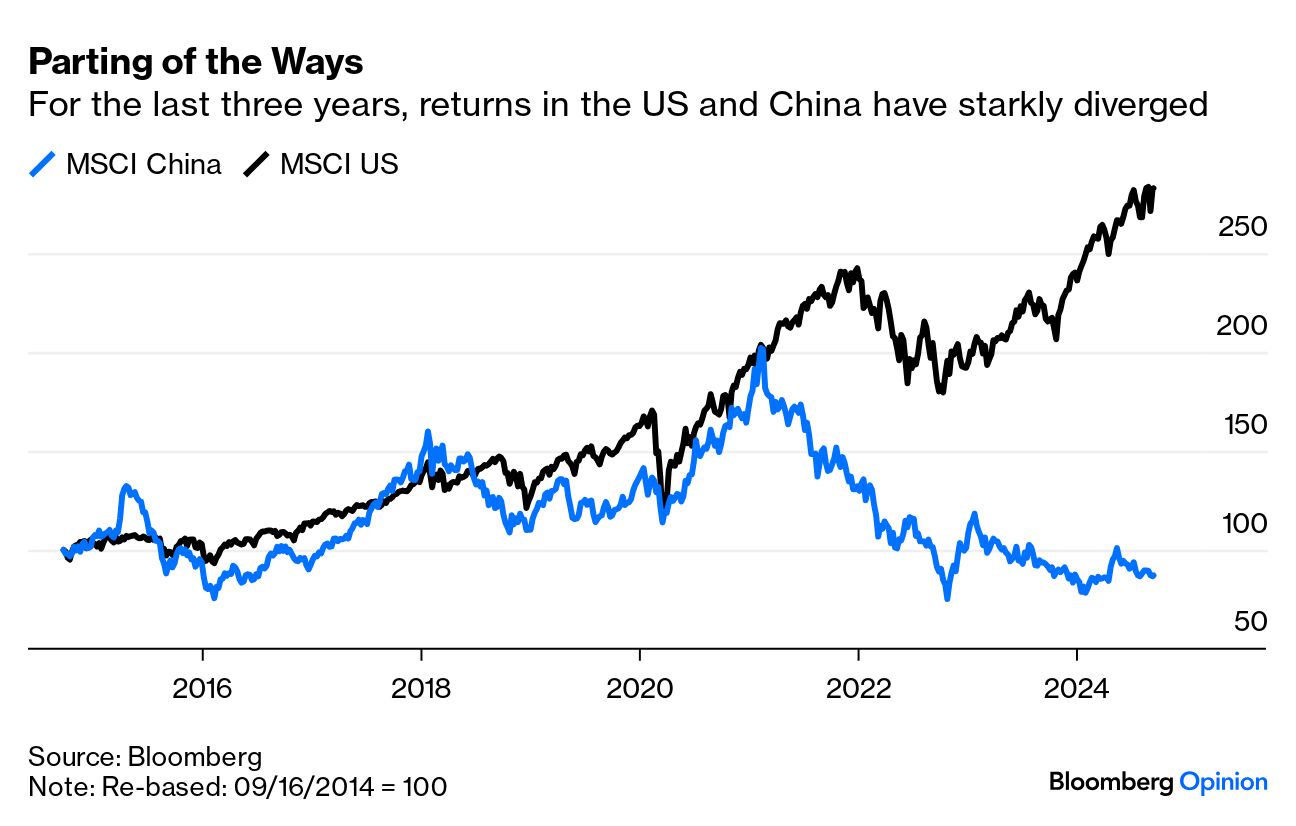

Whatever escape there is for households won't come easily. Given the right incentives, they could tap their excess savings to boost consumption. But Barclays shows those savings are mostly in time deposits, which made up 96% of all deposits in 2023: Anecdotal evidence suggests households prefer to hold deposits with maturities as long as five years to lock in relatively "high" interest rates as an environment of lower-for-longer interest rates seems widely expected. It has taken Japan about three decades to escape the economic slump. The asset value destroyed by property's downturn is estimated at $9 trillion, twice the size of China's equity market cap. The Chinese stock market meanwhile is looking alarmingly like Japan's: There's no quick fix. The experience of Japan and the US indicates it can take at least a decade to bring private-sector leverage down. Patience is required. — Richard Abbey For investors, one of the biggest consequences of China's difficulties has been to call into question whether it even makes sense to treat emerging markets as their own asset class anymore. The concept started as an inspired piece of branding by the International Finance Corporation four decades ago. The idea was to encourage Western investment in the developing world by spreading the risks across a range of markets and continents with different levels of development. The EM label worked far better than the original plan to call their new product a "Third World Investment Trust" (TWIT). Since then, the definition of emerging has moved from the IFC to the indexing group MSCI, and the indexes themselves have grown ever more sophisticated. We are now at the point where it's not clear that there's anything that differentiates economies on either side of MSCI's line, at least once the economic superpowers China and the US are removed. Over the last three years, MSCI's index for emerging markets excluding China and its EAFE index of developed markets excluding the US and Canada have been virtually identical: The great divisions in the world economy can be captured in full by comparing MSCI's index for the US (which in practice is more or less identical to the S&P 500) and China, in dollar terms. They used to move roughly together, which continued even after the Trump administration imposed tariffs in 2018. But since China started to clamp down on the private sector in 2021, the divergence has been astonishing: China matters to the rest of the emerging world far less than it once did. It has taken a growing share of MSCI's index over time, but more importantly, the entire EM complex has been regarded as one large leveraged play on the Chinese economy. As a result, the MSCI EM index performed exactly the same whether or not China was included. Over the last three years, they've decoupled. Like Europe or the developed countries of Asia, they now seem to be as dependent on events in the US as in China:  None of this means that people shouldn't invest in any given market; it just suggests that the concept of grouping disparate nations from Latin America, Eastern Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa and so on because they're all at much the same stage of development is past its sell-by date. Desisting from the EM label might lead to better-considered and targeted investments, without some of the weirder side effects of big emerging market flows. (For example, if money surges into EM funds because investors are excited about India, it will also flow into the tiny, very different and less liquid stock market of Colombia, causing price moves that have nothing to do with events there.) Further, John Paul Smith, a veteran emerging markets analyst, argues EM nations should never have been grouped together in the first place: The reality is that emerging equity markets lack any common secular drivers, the only real unifying features having been the initial phase of liberalisation in the 1990s, the impact of the rapid growth of China's economy from 2000 to 2010, and the relatively low level of valuations in the immediate aftermath of the series of crises from 1997 to 2002.

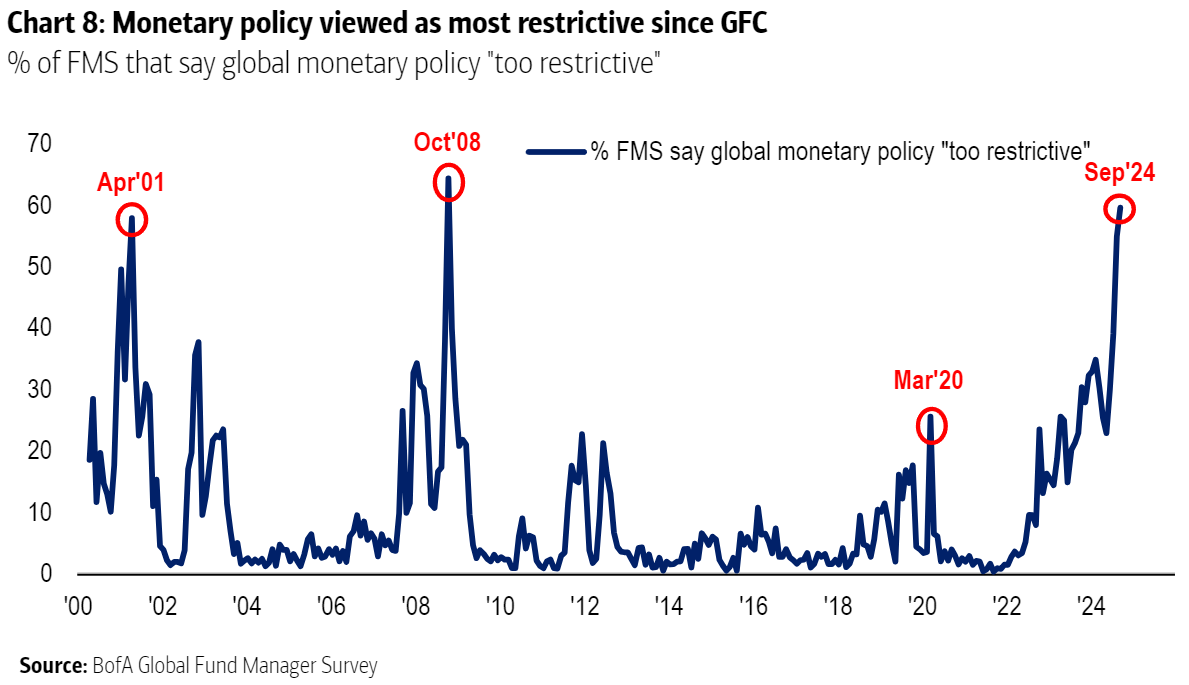

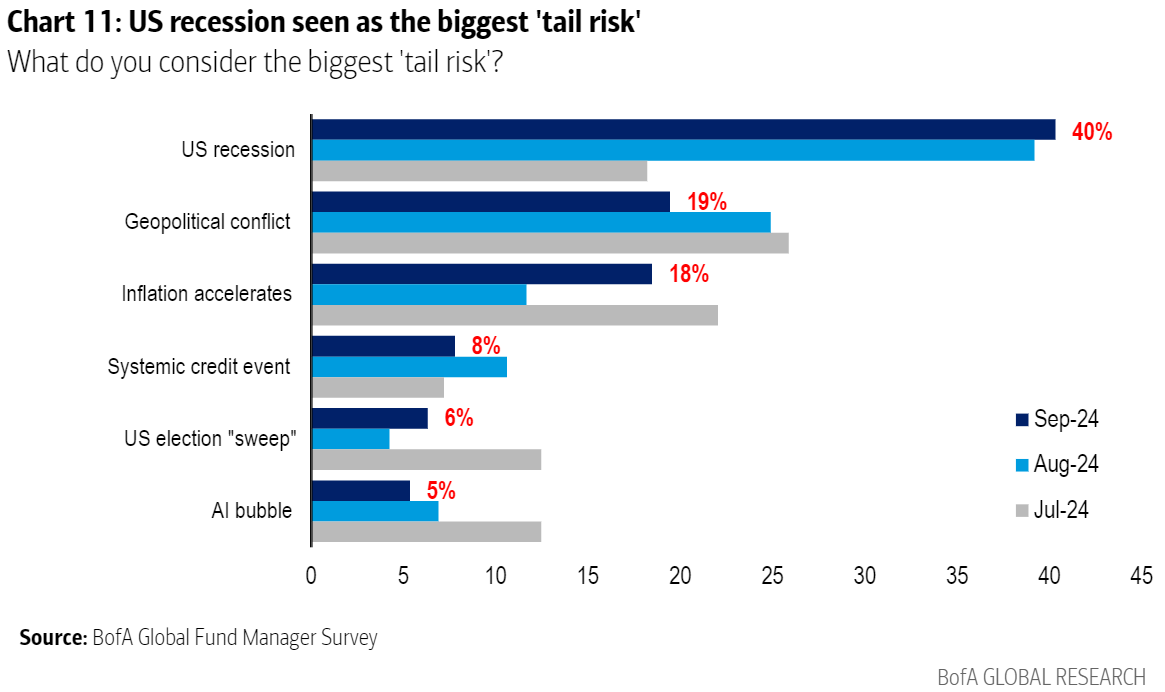

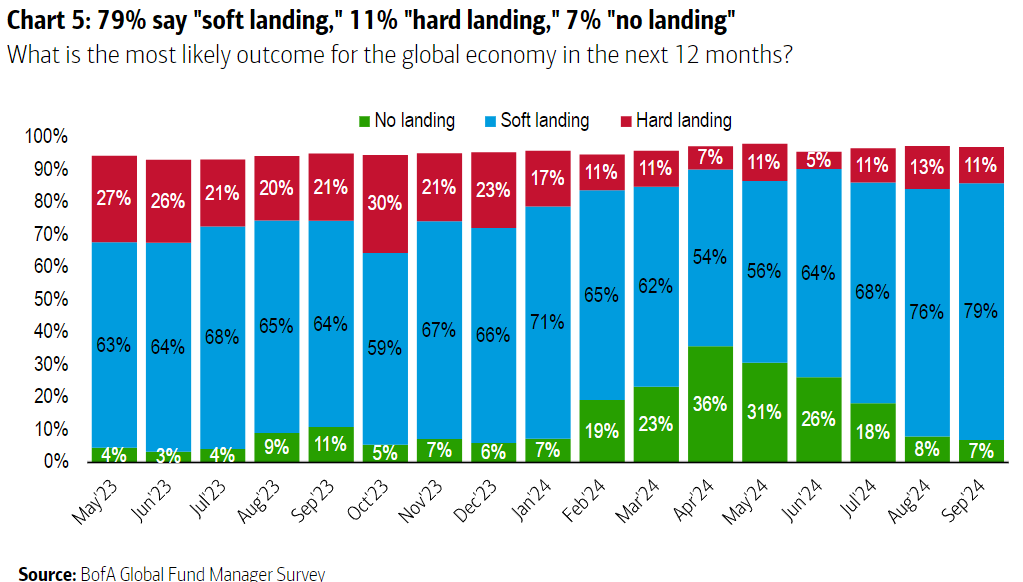

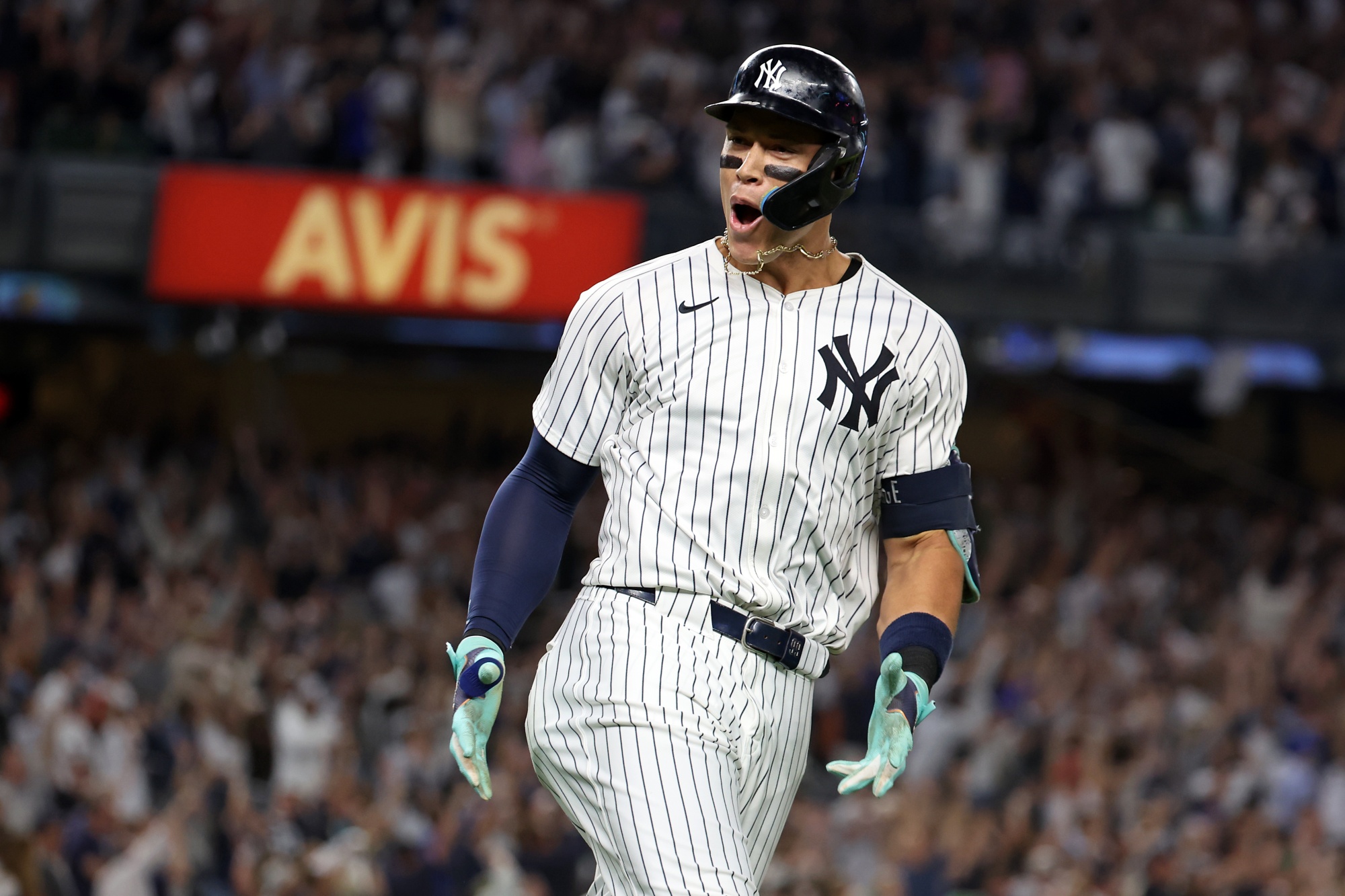

Smith points out that since the MSCI index started in 1988, only Israel and Portugal have made a sustained transition from emerging to developed (although Taiwan, Korea and Poland should probably join them). Since the brief window of opportunity for pro-market reforms after the fall of communism and then the crises of the 1990s, he says, "governments in key emerging markets have instead shifted towards state-directed, authoritarian and more recently autarkic governance regimes, with Korea and Taiwan the only significant exceptions." Outside the contest between the US and China, investors are better advised to look at all sectors and companies in the rest of the world on an equal footing. Emerging markets are no longer dancing to China's tune, and the opportunities they offer deserve to be viewed the same way as their competitor companies in the developed world.  The waiting is over. Photographer: Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg Within a few hours, the Federal Open Market Committee will announce a rate cut for the first time in four years, having generated more uncertainty about the extent of their move than has been witnessed in more than a decade. We've already written a lot about it. For now, here's some evidence that the market really wants a cut of 50 basis points (not just 25). The latest BofA survey of global fund managers shows that more believe global monetary policy is too restrictive than at any time since the crisis of October 2008: They think this because worries about a US recession are gaining traction. In a world riven by geopolitical rifts, a US downturn is now considered the biggest tail risk facing the market. The threat of accelerating inflation was named by less than half as many respondents — so it's clear they would think the situation called for a bigger cut: Despite this, confidence that the global econoy is heading for a soft landing is now its greatest since BofA started asking the question in May last year. It's predicted by 79% of respondents, while 7% foresee an overheating "no landing" and 11% expect a hard landing: If a soft landing now looks so likely, even as the risks of a recession are perceived to be rising while monetary policy is thought way too tight, this suggests that either a) markets are sure that the Fed will cut drastically (and would probably react very badly otherwise), or b) fund managers' views are self-contradictory and unlikely to be fulfilled. As for the imminent decision, here's yet another way to frame it. The crucial distinction is between rates of change and levels (or between flow and stock). Do US interest rates need to be so high with inflation coming under control? No, they don't; so a 50-basis-point cut might be in order. Do rates really need to be cut fast when the economy doesn't as yet appear to be in trouble? No, they don't. Focus on the level, and you probably arrive at a bigger cut; focus on the change at the margin (as economists are trained to do), and you can only justify a smaller one. We'll know soon enough now. With the Fed facing a binary choice, a reminder from baseball that either might go wrong. The Boston Red Sox were in New York for a four-game series this weekend. On Friday, they led 4-1 in the seventh, but the bases were loaded with the Yankees' fearsome Aaron Judge coming to the plate. Cam Booser, on the mound for Boston, made his major league debut earlier this season. Previously, he'd spent six years working as a carpenter. I was screaming at the television for Judge to be intentionally walked. It would cost a run, but rob him of the chance to score four in a Grand Slam. Booser pitched to him. He hit a Grand Slam. The Yankees won.  Judge-ment. Photographer: New York Yankees/Getty Images Next day, I was at the stadium as the Yankees' ace pitcher Gerrit Cole mowed the Sox down. In the first three innings, only one Red Sock reached base, when Cole hit slugger Rafael Devers with a pitch. Devers is a great hitter but not as good as Judge; Cole is a much better pitcher than Booser. However, in the fourth inning, with one out and nobody on base, Cole — who has a terrible record against Devers over the years — decided just to let him walk. The worst that Devers could have done was score one run. There was confusion. At first, no one in the crowd could work out what had happened. Once it became clear that he'd ducked the contest, Cole suffered derision from his own fans and from the Red Sox bench. All initiative was lost. Cole gave up three in the inning. The Yankees lost 7-1. Know your limitations when you have choices like this, but also go in with a clear idea of the worst that could happen. Both teams made terrible mistakes, obvious to everyone in real time. Just grasping how much was at stake would have changed the decisions, and possibly the result of both games. So, no pressure on Jay Powell and his chums then… Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Javier Blas: OPEC+ Faces a New Problem: A Texas Gas Pipeline

- Conor Sen: Mortgage Rates Puzzle Is a Worry for Housing and the Fed

- Kathryn Anne Edwards: Make Social Security the Model to Fix the Minimum Wage

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment