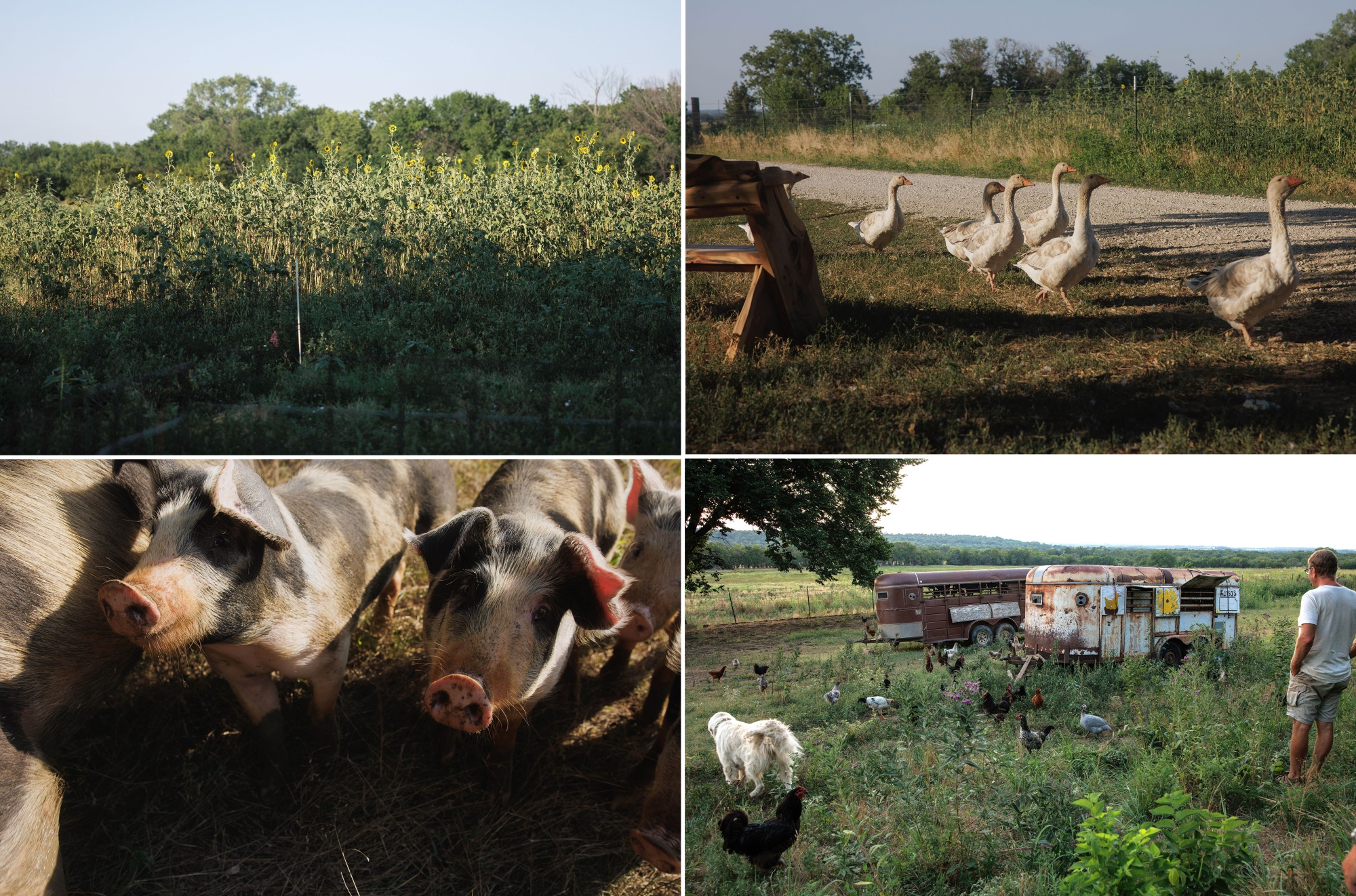

| By Miranda Jeyaretnam In Kansas, where a prolonged drought has killed crops and eroded the soil, Gail Fuller's farm is like an oasis. Sheep, cows and chickens graze freely on crops and vegetation in a paradisiacal mess. But if Fuller's farm were to be hit by a tornado or flood, or be seriously impacted by the drought, he would be alone in footing the bill. That's because his farming practices aren't protected by federal crop insurance, a nearly century-old safety net that hasn't adapted to the climate change era. Fuller is one of a growing number of farmers who are uninsured or under-insured because the industry doesn't support switching from traditional to regenerative farming, an approach that has the potential to sequester enough carbon to halve agricultural emissions by 2030. Regenerative farming reduces emissions by soaking up carbon dioxide through photosynthesis, storing carbon in the soil and capturing nitrogen that would otherwise runoff into nearby streams.  Pigs and cattle share a field at Fuller Farms. Photographer: Chase Castor/Bloomberg  Iron Weed grows among other plants and grasses in a pasture at Fuller Farms. Photographer: Chase Castor/Bloomberg These farming practices often involves interspersing different crops in the same field and growing lower-yielding perennial plants. However, this can create issues for insurers. Like health, car or property insurance, appraisals for losses or damages rely on standards — known as Good Farming Practices — that ensure low yields aren't caused by mismanagement. A farmer caught growing different crops between rows or terminating their cover crops too late, for example, is at risk of having their insurance claims denied.  Gail Fuller farmed monoculture cash crops and raised feeder cattle until a change of heart directed him toward regenerative farming practices. Photographer: Chase Castor/Bloomberg The US Department of Agriculture has introduced reforms and alternatives to the crop insurance program to accommodate climate risks over the past decade, including adding coverage for new crops and a $5-per-acre incentive to plant cover crops during the offseason. The Risk Management Agency, which controls federal crop insurance, also has expanded its coverage of certain climate-smart practices, like lowering water use, cover cropping and injecting nitrogen into the soil, rather than layering it on the soil's surface. Farmers must still follow specific rules, such as terminating their cover crops early enough, which some scientists think limits how much these practices can reduce emissions.  Gail Fuller's farm uses a variety of regenerative farming techniques such as crop diversification and growing perennial plants. Photographer: Chase Castor/Bloomberg The regenerative farming movement is relatively small, but it's gained steam in recent years thanks to federal support and agribusinesses eager to align their supply chains and sustainability goals. But for now, the push for changing insurance rules still relies largely on farmers like Fuller and Rick Clark, a third-generation farmer from west central Indiana who has been uninsured for six years because he practices regenerative farming. When he's not working his farm — which utilizes cover crops across all 7,000 acres — Clark teaches other farmers how to eliminate chemical fertilizers and use cover crops on their farms. "We have to make sure the path towards change is an easy path," Clark said. One of the biggest challenges uninsured farmers face is from their lending institution, which often requires them to have an insurance policy to continue receiving loans. Clark testified in front of Congress in late 2022 on behalf of Regenerate America, a coalition that lobbies for agricultural reform. The day after Clark testified, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, President Joe Biden's landmark climate law that includes a $19.5 billion investment into USDA conservation programs. He felt like he had a small part to play in that. "At some point when you're in there, you wonder if anybody's even [listening] to what you're saying," Clark said. But then, "you feel like maybe your words don't fall on deaf ears and maybe there are people who are truly paying attention." Read the full story here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment