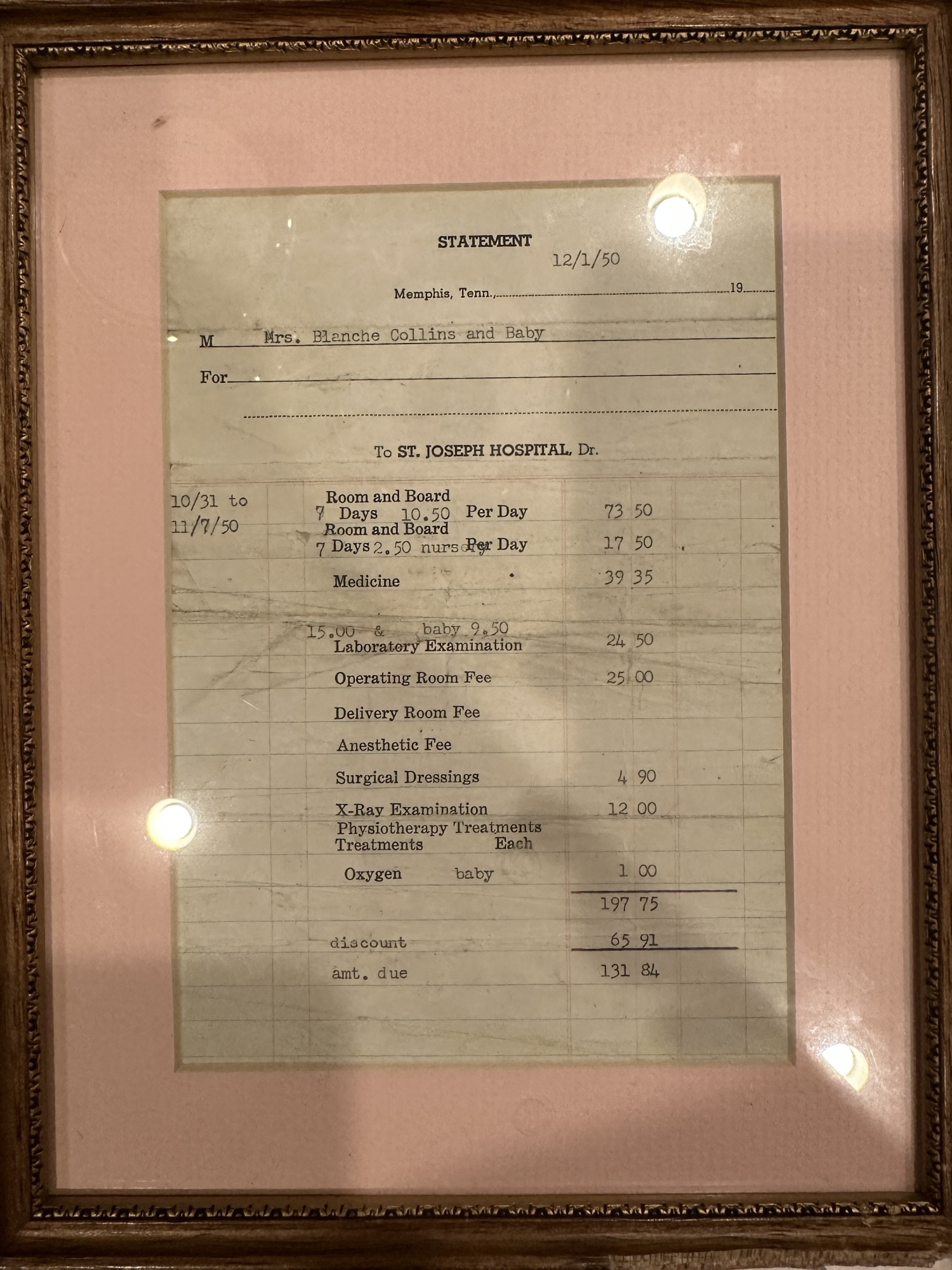

| A few months ago, while sifting through boxes in my mother's basement, I found something interesting: The 1950 hospital bill from when my grandmother gave birth to my mom.  Claire Suddath's grandmother's 1950 birth certificate at St. Joseph's Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee Photographer: Claire Suddath It fascinated me, and not just because my grandmother inexplicably framed it. I just couldn't get over what it said. In 1950, it cost my grandmother $131.84 to have a baby. That works out to about $1,667.12 today. Before insurance. And she stayed in the hospital for seven days!

Meanwhile, when my daughter was born in 2020, the total cost of her birth was nearly $90,000. Two years later her brother, a much simpler delivery at the same hospital, cost around $26,000. Again, this was before insurance. I knew that healthcare costs in the US had risen exponentially over the years, but I'd never been confronted with such stark, visible proof until I saw my grandmother's bill.

In fact, I spent nearly $2,500 on pelvic floor physical therapy alone after my daughter was born. She was delivered with forceps (hence the $90,000 hospital bill), which can absolutely wreck a woman's body. Unless I wanted to spend the rest of my life peeing whenever I sneezed, I needed physical therapy, but it wasn't covered by insurance. All told, I've spent thousands of dollars on my own health care needs related to giving birth. And I'm someone with high-quality, employer-provided health insurance.

My experience is pretty typical for an American mom. Different studies report different figures but in general, people with employer-provided health insurance in the US are charged about $20,000 to have a baby (more if they need a C-section) and incur somewhere between $2,600 and $4,500 in out-of-pocket costs. Birth complications, or if a baby spends time in the NICU, can drive prices up even higher.

Part of the reason for this exorbitant price tag is the general rise in healthcare costs, says Cynthia Cox, a vice president at the health research organization KFF. But it also reflects the insurance industry's recent shift to plans with high deductibles.

"High deductibles are supposed to make people think twice about the cost of care and if they really need it," says Cox. "Although in the case of childbirth that doesn't make sense. Obviously you need it."

Technically, Cox says, things are better than they used to be. Before the 2012 Affordable Care Act, many private insurance plans didn't cover pregnancy at all. "Insurers didn't want someone to get pregnant and only then buy insurance, so they didn't cover it," she explains. Unless a woman qualified for Medicaid or already had insurance through her job, she didn't have a lot of options.

"There was outright discrimination of women, outright exclusion of maternal benefits. Some women were left with catastrophic costs," says Adam Gaffney, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School who specializes in health policy research. "It's not a time we look back on fondly."

Alison Opalko-Berry was 20 years old and working two jobs, as a substitute teacher and a waitress, when she gave birth to her first child in 2009. She remembers the stress of trying to afford medical care in those pre-ACA years.

"I remember researching pregnancy insurance and being like, 'I don't know if this is worth it,'" she says. Thankfully, she did find an insurance plan that covered her pregnancy, because her son arrived four weeks early and racked up a $100,000 hospital bill when he was born. Even with insurance, Opalko-Berry says she owed about $3,000. But with such a low income—as a substitute teacher she made $100 a day—she was already struggling to afford other baby-related expenses. "I went into debt and was paying that off for many years," she said. Unfortunately, going into debt after giving birth is depressingly common in the US. Last year, researchers at Harvard Medical School looked at the correlation between childbirth and debt and found that nearly 20% of new mothers in America struggle to pay their medical bills after having a baby.

"This is an unnecessary problem that we've created for ourselves," says Gaffney, who co-authored the study. "There are countries with no copays or deductibles for anything, and this does not happen."

He's right. In most developed countries, the cost of having a baby is much lower, something Opalko-Berry learned first hand when she married a German man and moved with him to his home country. In 2020 she and her husband had another baby, for which she was billed $2,166—about on par with my grandmother's bill, in today's dollars. But that's not what Opalko-Berry had to pay.

Germany has a universal healthcare program called statutory health insurance; the government paid the bulk of Opalko-Berry's bill, leaving her with an out-of-pocket cost of just $53, and only because she had requested a private hospital room. In 2021 she and her husband had a third child and again paid almost nothing. In other words, the birth of her German-born children cost just 1.7% of what her American-born one did. Opalko-Berry has been shocked by how affordable having a family is in Germany compared with the US. Once, she rushed her oldest child to the emergency room because he had an allergic reaction to nuts and when she inquired about the bill a doctor replied, "You must be American." She now runs TikTok and Instagram accounts under the handle @usa.mom.in.germany, highlighting the differences. "It's one thing to hear rumors about another country but when someone discusses the nitty gritty of their personal experience, I think it helps people understand," she says. "The social support system, the things available to families here, it's just so different."

Judging from my grandmother's 1950 hospital bill, it used to be different here, too. |

No comments:

Post a Comment