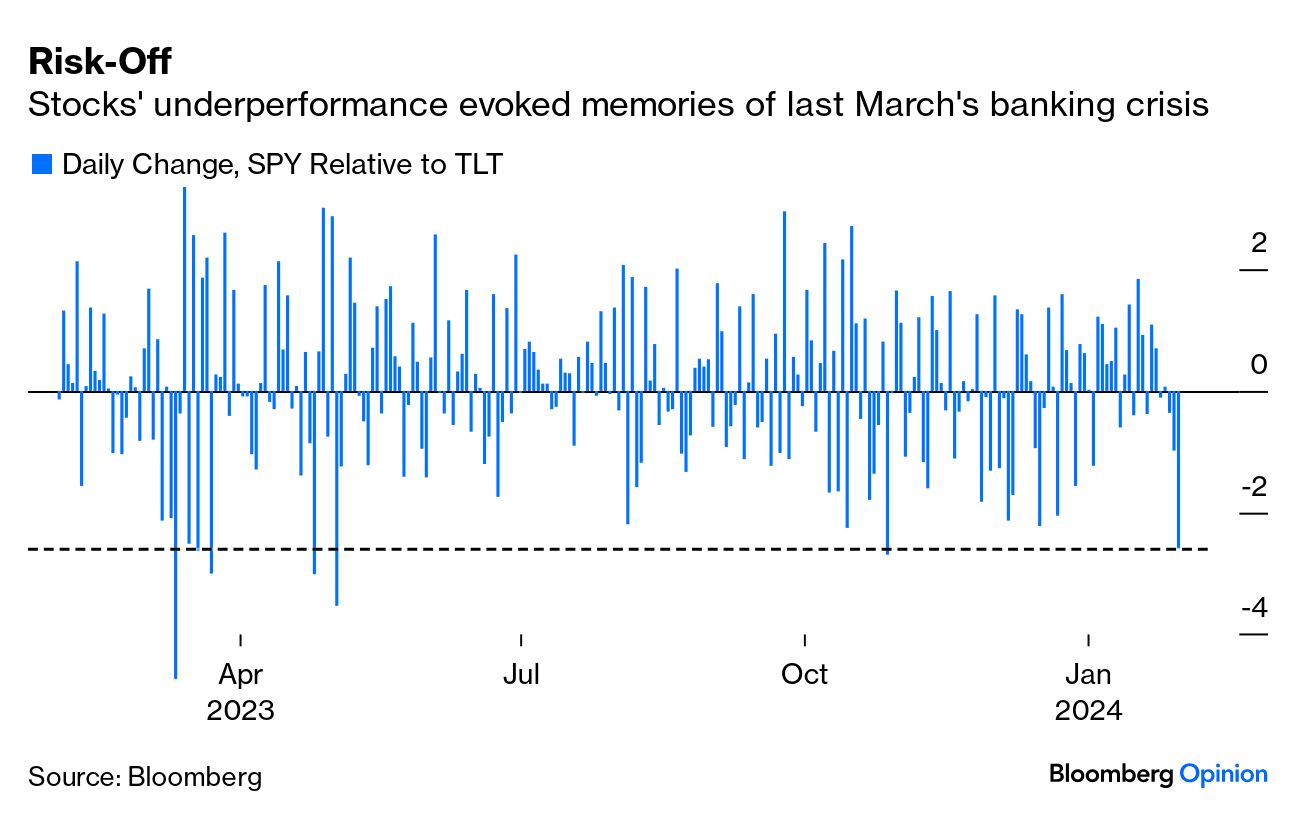

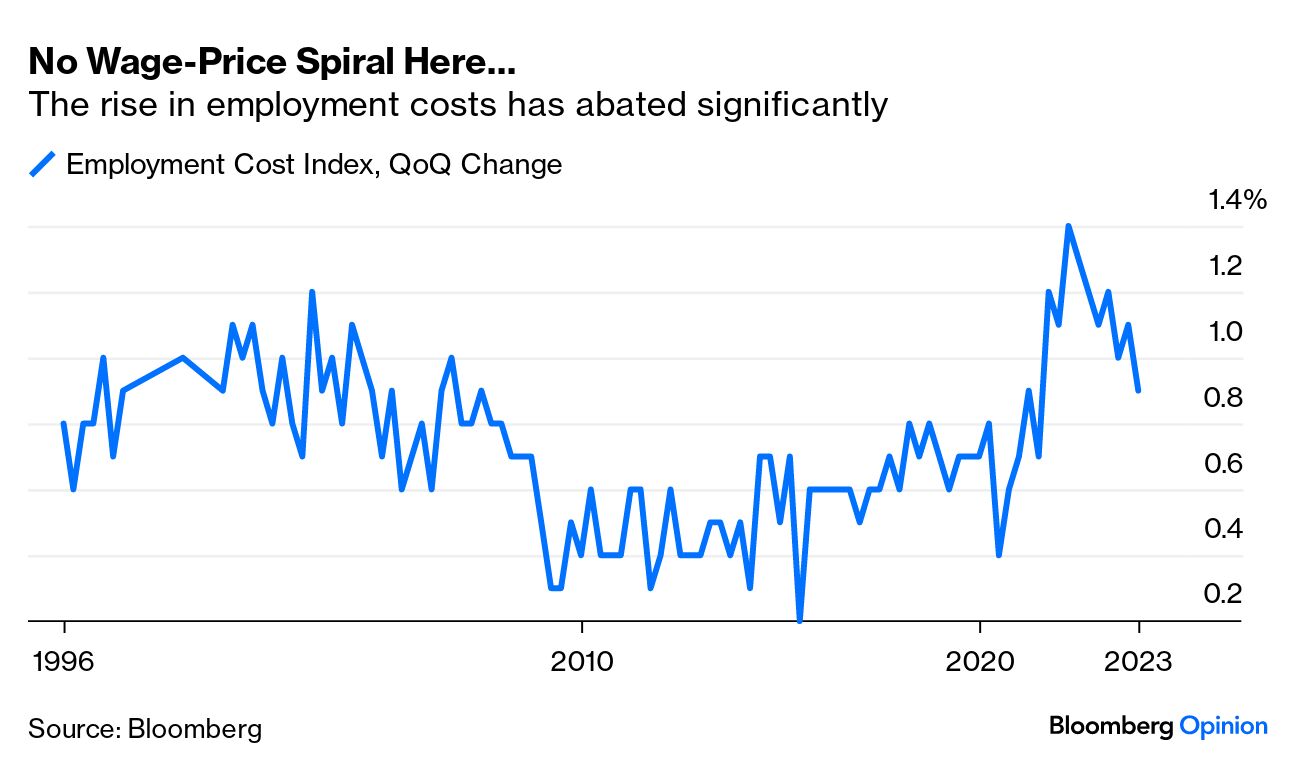

| The fed funds rate is unlikely to be cut in March when the Federal Reserve's monetary policy decision makers hold their next meeting. We can say that with some clarity because Chair Jerome Powell voiced it in as many words, saying that it was "not the most likely case or the base case." The official Federal Open Market Committee statement erased language it had used previously that it held a bias toward more hikes, but that had been universally expected. Such clear guidance for March had not been, and it had an impact. The stock market appeared to have put more weight on imminent cuts than anyone else. A busy day had already included: results from Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp., news of serious difficulties for New York Community Bank that pushed its stock down 45%, an announcement from the Treasury that it was going to be auctioning over the next three months somewhat more longer-term bonds than had been expected, and macro news suggesting the labor market might be cooling down a bit. Despite all of this, the circumstantial evidence is that it was Powell's words on a March cut that substantially did all the damage:  Stocks had the worst day in some months. Meanwhile, bonds enjoyed a rally, swallowing the bond supply news without difficulty. Instead, the fears around New York Community Bank sent people rushing to buy Treasuries, largely on the theory that renewed banking trouble would force the Fed to ease. Yields rose during Powell's press conference, without getting back to their previous high, and then sank as traders shifted positions for the end of the month: This was a vintage risk-off day, with money moving out of stocks and into bonds. The problems at NYCB, which took over some of the assets of the failed Signature Bank last year, played a big role. A loan-loss provision of $550 million, mostly for real estate, came as a nasty shock, and drove a big asset-allocation move. If we use the SPY and TLT exchange-traded funds as proxies for the S&P 500 and for Treasury bonds of 20 years or more, we find that this was the sharpest risk-off day since the sudden raft of bank failures last March:  There were plenty of cross-currents, but the nerves over Big Tech also mattered a lot. To quote Peter van Dooijeweert, head of defensive and tactical alpha at Man Group: "Regional banks are very weak. Usually, when regional banks blow up you're supposed to buy tech. And when bonds rally you're supposed to buy tech." Wednesday's trading was therefore a big exception to the rule, largely because tech companies are failing to fulfill their rosiest earnings expectations. Meanwhile, the shift in expectations for rate cuts is much less than at first appears. The implied odds on a March move rose to two-in-three and then fell to one-in-three during the day, but things weren't so different at the close of trading. This is the implicit odds of a March hike or cut, as calculated from fed funds futures by the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities (WIRP) function: For the longer term, Powell sounded enthusiastic enough about the chances that inflation was beaten that expectations actually moved toward a rather more aggressive series of cuts. December saw a big shift that was subsequently dialed back. The fed funds futures curve ended Wednesday predicting more cuts by the end of the year than it had on Tuesday — it's now close to the optimism registered at the start of 2024: As for the day's data, it generally aligned with a soft landing. Most importantly, the employment cost index, covering the full expense of employing people, had its smallest increase in two years during the last quarter of 2023. It was the acceleration of this measure late in 2021 that appeared to jolt the Fed toward hiking, so this is significant:  Ultimately, Powell repeated several times that he thought the improvement in inflation data was good, but that he needed more — not necessarily better data. The subtext is that he's determined not to repeat the mistakes of the 1970s and cut too soon, particularly when (unlike back then) there are no problems in the employment market. Once the Fed has seen enough, he made clear that the FOMC would probably cut several times this year (he mentioned that in the "dot-plot," the median FOMC member called for three cuts). In other words, he's doing a good job of threading the needle, and calibrating a response that will allow an economic soft landing. Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Santander, offered, I think, a reasonable summary: Powell was very clear. The data seen over the past six months on core inflation (core PCE deflator running at a 1.9% annualized rate) is exactly what the Fed is hoping to see, but policymakers simply need to see more. The passage of time and continued benign readings are necessary to move the Fed to begin to cut rates. I can confidently forecast that time will pass, but, I doubt that the inflation data will be as good over the next six months as it was in the last six, which is why I believe that easing will come later than the market is currently pricing.

As Stanley points out, risks have not gone away. Macro data surprises could change things in either direction, and if NYCB proves the harbinger of serious problems for banking, then rates will need to come down quicker. As for the stock market, Wednesday's events underlined how much it has come to rely on the big-tech names. Between the market's Thursday close and Friday's open, traders will have to deal with results from Apple Inc., Meta Platforms Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., and with the January non-farm payroll figures. There's plenty more excitement ahead. — Reporting by Isabelle Lee Within hours on Wednesday, Delaware and New Hampshire, two of the smallest states in the union, hit important blows for the power of investors, and the ability of shareholders to exert influence over the companies they own. A Delaware court's decision to uphold a shareholder complaint, and invalidate the ludicrous $55 billion pay package that Tesla Inc. agreed in 2018 to pay Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk, is a breathtaking story, but also an uplifting one. Tesla's corporate governance has long been highly questionable — to put it mildly — even if Musk's sheer omnipresence in contemporary life makes him a valuable asset. In New Hampshire, a committee of the state's House of Representatives voted 16-0 to recommend blocking legislation that would have made it a criminal offense for the state's pension funds to invest on an ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) basis. That means that New Hampshire's investment managers might, after all, be allowed to avoid companies with poor corporate governance (like, maybe, Tesla). The broader message is that the wave of uncritical adulation for ESG investing has been followed by an even more overblown wave of support for anti-ESG measures, and that common sense might just be starting a fightback. The precise wording of New Hampshire's proposed bill made it a criminal offense to invest "based on non-financial considerations (that) may include environmental, social and governance criteria, which have shown to produce lower returns compared to investment decisions based on financial considerations alone." First, note that it's contentious whether ESG factors really do lead to worse returns. The academic literature is still unclear, but anyone who wants to do ESG investing can find a report from somewhere that will justify their approach. Second, note that New Hampshire was setting out to invalidate investing on the basis of governance, even though that does have very direct financial effects. Did it really mean that investors couldn't take into account Tesla's dreadful corporate governance and decide not to invest, or that shareholders couldn't take action against excessive pay awards? Finally, and most important, it would have erased all "non-financial considerations." Anti-ESG at this point amounts to a hugely prescriptive attempt to strip managers of all their discretion, and appears to have a naive belief that there is one clear financial approach to maximize returns. This is a little like the notion that there was one agreed version of "science" that needed to be followed during the pandemic. The point of active investing is to try to find areas where the herd has it wrong, and to spot factors that could help a company do better than might be predicted from its current financials alone. The last two decades have seen an academic arms race as finance professors have tried to identify investment factors that lead to better performance. In 2015, research led by Campbell Harvey of Duke University identified 316 putative factors in the literature. Many relied on data-mining, and others found smaller anomalies that could soon be arbitraged away — although not without making some money for the person doing the arbitraging. Big Data, and the increased opportunities offered by machine learning and artificial intelligence have permitted fund managers to go ever further in search of an edge. Many of these factors would fit under an ESG umbrella, and the bulk of them are "non-financial." So a blanket ban on non-financial considerations would have prohibited fund managers from trying their utmost to beat the market — even though that's exactly what we want them to do. There are deeper dangers in this. Buying index funds is a good starting point for most of us. But big, passive investment can distort markets. Anti-ESG at this point is shifting toward telling investors they mustn't put money into anything other than big indexes. That would exacerbate herding, and further diminish the market's ability to distribute capital where it can be best used. With the traditionally pro-business Republican party increasingly believing that it has the right to tell businesses what they can and cannot do, brace for a new battle. Should investment managers be subjected to political pressure over how they invest? Both the ESG and Anti-ESG factions currently seem to have no problem with that. Which is dangerous. Ed Farrington, a New Hampshire-based fund manager and the incoming president, North America, at Impax Asset Management, said this to the committee (as quoted in Pensions & Investments): Criminalizing investment choice and forbidding the inclusion of ESG factors is a close step to substituting the opinions of government officials for the knowledge of investment professionals.

Well said. What are the most popular love songs? After dredging the 1,000 most popular Spotify playlists with "love songs" in the title, a QR code generator called QRFY has kindly offered a ranking of the songs on the most lists. With Valentine's Day coming up, it might be of interest. The list goes as follows: 1. Perfect by Ed Sheeran 2. All of Me by John Legend 3. Say You Won't Let Go by James Arthur 4. I Wanna Be Yours by the Arctic Monkeys 5. Thinking Out Loud by Ed Sheeran (again) 6. Right Here Waiting by Richard Marx 7. I Will Always Love You by Whitney Houston 8. I Want to Know What Love Is by Foreigner 9. Glory of Love by Peter Cetera 9. Dandelions by Ruth B. Just outside the top 10 were You Are the Reason by Calum Scott, Against All Odds by Phil Collins, and Careless Whisper by George Michael. You might well have noticed that there's a lot of schlock on this list. Some possible additions that stay as romantic, but might be more worth listening to: Something by The Beatles, and Wonderful Tonight by Eric Clapton (inspired by the same woman), Woman by John Lennon, More Than This by Roxy Music, Guilty by Billie Holiday, True by Spandau Ballet, A Whiter Shade of Pale by Procol Harum, Lovesong by The Cure, Hello by Lionel Richie, or The Man With the Child in His Eyes by Kate Bush (written at the age of 13). Any more out there? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment