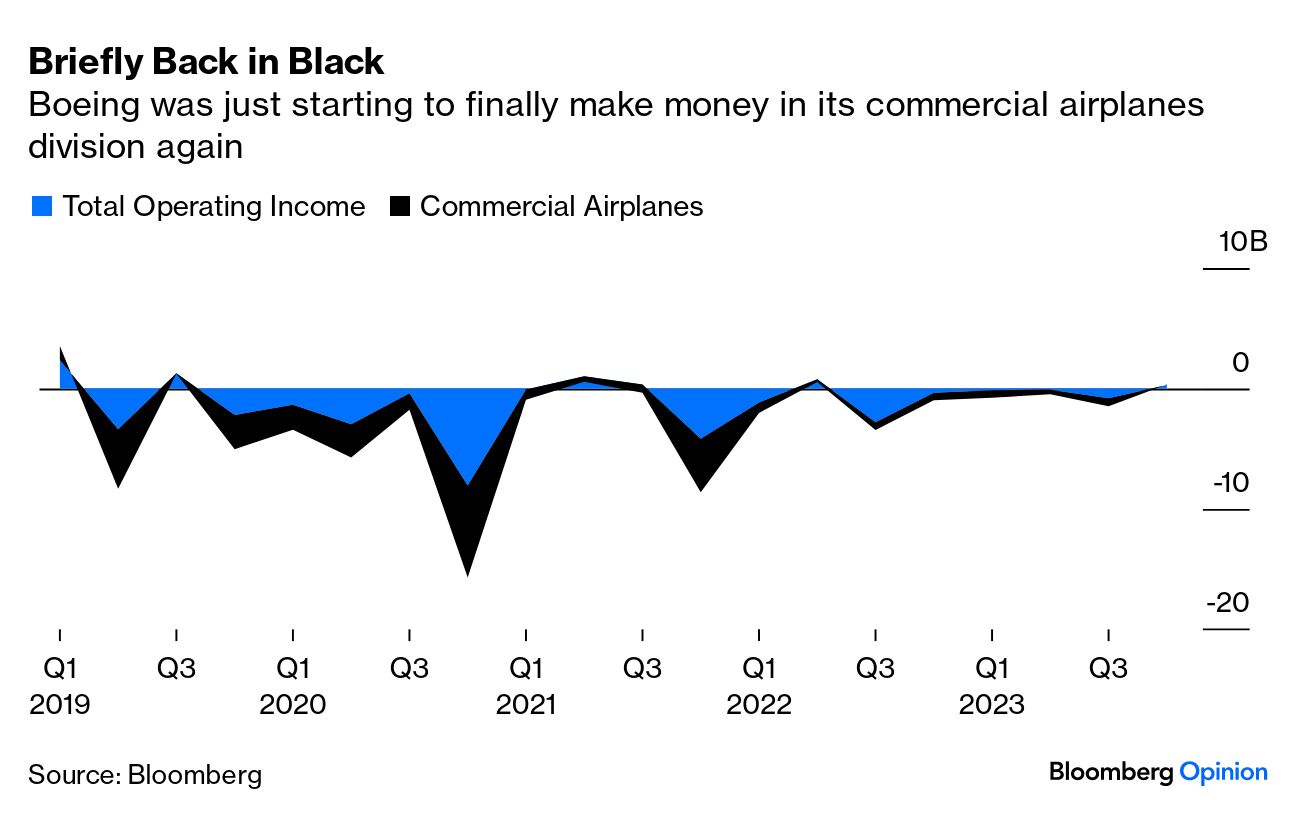

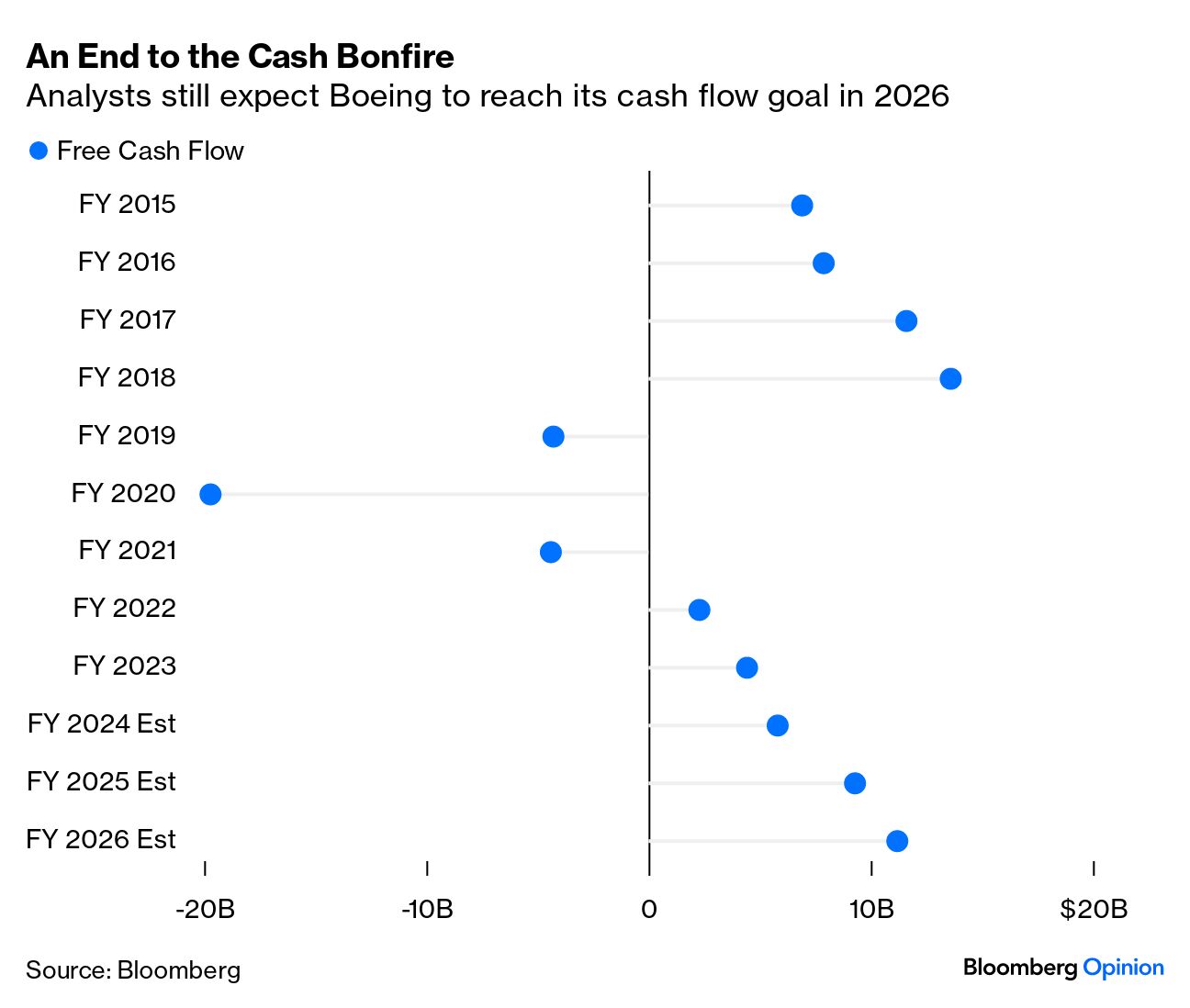

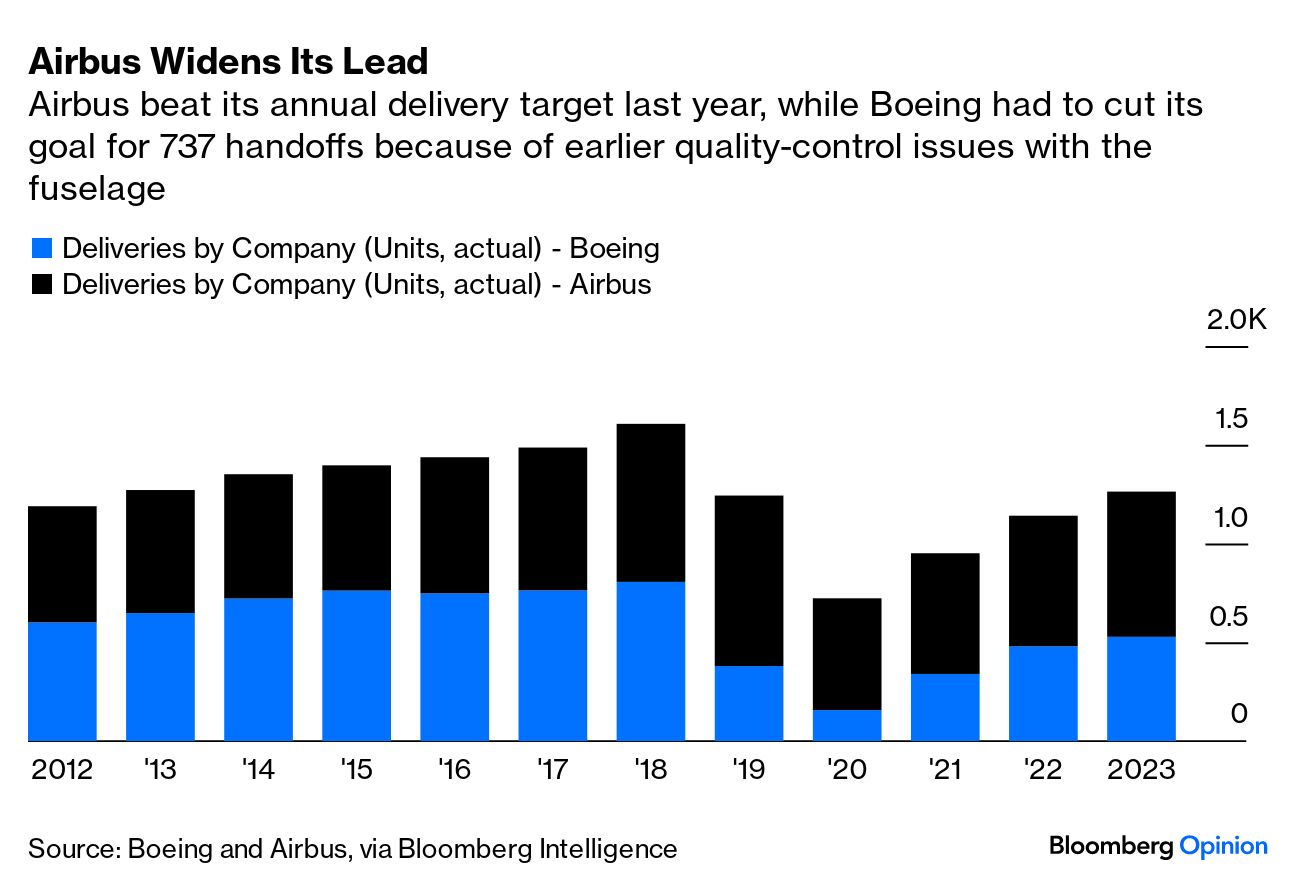

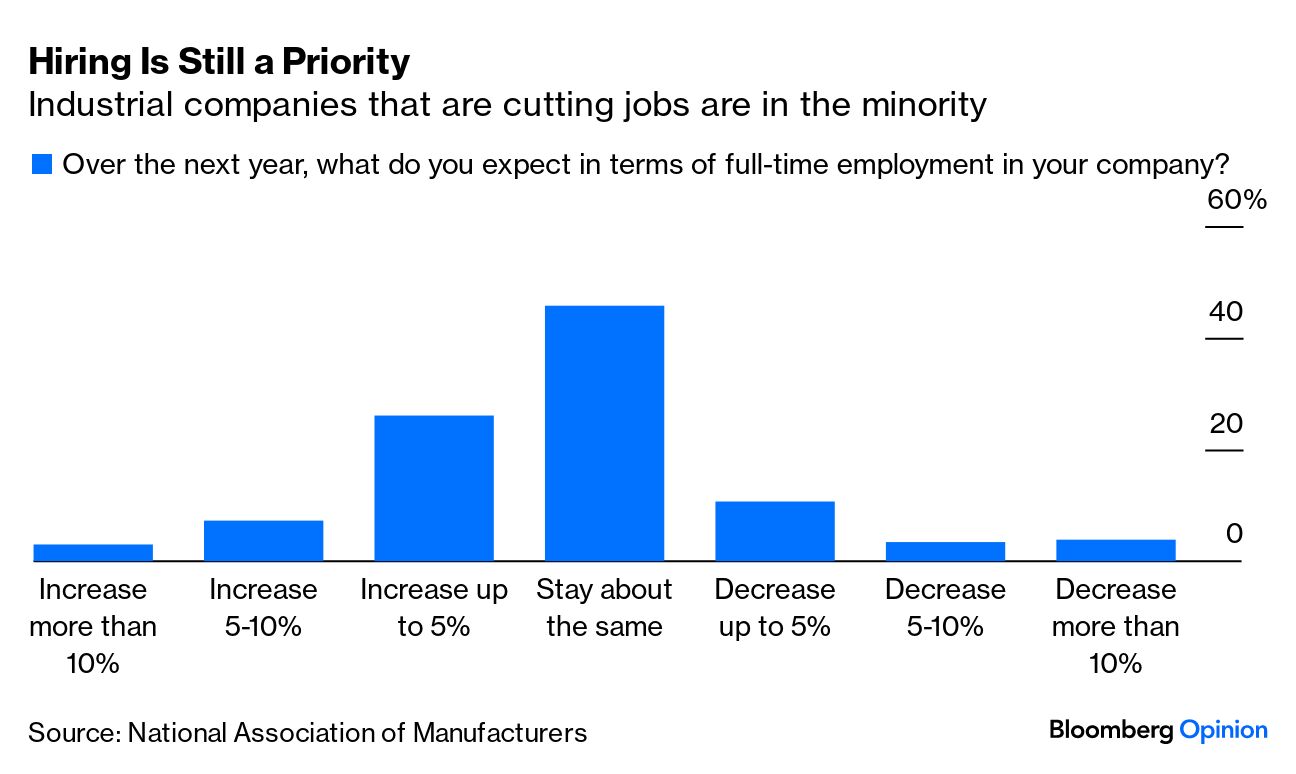

| Have thoughts or feedback? Anything I missed? Email me at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net If it wasn't for a door panel blowing open on a plane midair, things would actually be looking up for Boeing Co. The planemaker reported fourth-quarter results on Wednesday. The actual numbers are obviously an afterthought in the wake of the Jan. 5 Alaska Airlines flight that could have easily ended in disaster for its passengers and certainly has had catastrophic consequences for Boeing's reputation. But that doesn't mean the figures aren't telling. Boeing is not just any company; for better or for worse, it's a national champion, a large military contractor and the only US manufacturer of large commercial aircraft. Its ability to generate profits and cash flow from deliveries of safe airplanes isn't just crucial for shareholders but for the scores of airlines that are counting on Boeing planes to ferry passengers around the world and ultimately for US national security. Boeing generated $3 billion of cash flow in the final months of 2023, with the intake likely buffered by customer deposits from a busy Dubai Air Show and the largest ever monthly sales for the 737 Max model in December. The end-of-year surge pushed Boeing's annual free cash flow to $4.4 billion — the highest level since 2018, when the first of two fatal Max crashes occurred. Boeing made money from its commercial aerospace operations for the first quarter since the second Max crash in March 2019 prompted a nearly two-year grounding of the plane.  Separately this month, Boeing delivered its first Max jet to a Chinese customer in five years, setting the company up to cash in on a glut of inventory designated for the country that's been piling up in factory parking lots. Boeing had about 200 Max planes in inventory at the end of 2023, roughly 140 of which were built before last year and are mostly earmarked for customers in China and India, Chief Financial Officer Brian West said Wednesday on a call with analysts. The company declined to provide specific guidance for 2024. "This increased scrutiny — whether from ourselves, from our regulator, or from others — will make us better," Boeing Chief Executive Officer Dave Calhoun said in a memo to employees. "We will go slow, we will not rush the system and we will take our time to do it right. While we often use this time of year to share or update our financial and operational objectives, now is not the time for that." He's right, of course but the relatively strong fourth-quarter results underscore why this latest crisis is so painful for everyone involved. Boeing's Max jets were supposed to be the safest airplanes in the world after the company itself, regulators and others pored over every inch of the jet during the grounding. They weren't. The company's quality-control issues were supposed to be under control after two separate snags disclosed last year that were linked to fuselage maker Spirit AeroSystems Holdings Inc. and involved incorrectly installed rear fittings and oblong fastener holes. They weren't. A report from the Seattle Times painted a damning picture of sloppy workmanship and gaps in reporting systems that led to missed quality inspections on the Max 9 jet involved in the Alaska Airlines incident. Airline reports of loose bolts on many other jets suggest this wasn't an isolated incident but a symptom of deeper flaws in both Boeing's manufacturing processes and safety culture. Read more: Boeing Finds Accountability a Little Too Late The Federal Aviation Administration has allowed airlines to start flying the Max 9 model involved in the Alaska Airlines incident again after grounding the jets for several weeks. But the regulator has capped future Max production increases at Boeing until it's satisfied that the company's quality-control systems are rigorous enough and is planning to significantly increase oversight of the company. Earlier this week, Boeing pulled its request for an exemption from safety regulations that would have allowed the company to put its Max 7 jet into service before rolling out a fix for a de-icing system that could damage engine parts under certain conditions. Boeing said Wednesday that redesigning the de-icing system could take about a year. The certification timeline for the larger Max 10 model is anyone's guess. Southwest Airlines Co. has since said it no longer expects to take delivery of any Max 7 jets this year, while Max 10 customer United Airlines Holdings Inc. has said it's building an alternative fleet plan that doesn't include the plane. All of that will weigh on Boeing's future cash flow and profits. But the company didn't explicitly scrap its long-term goal of generating $10 billion in free cash flow by 2025 or 2026. "We're still confident in the goals we laid out for '25, '26, although it may take longer in that window than originally anticipated, and we won't rush the system," West said on Wednesday.  While Boeing is officially holding 737 production at a rate of 38 planes a month, it will keep the supply chain on track for the output ramp-up that the company had been targeting before the latest crisis. Aerospace manufacturers big and small have continued to struggle to hire and train the workers they need after laying off thousands during the pandemic. Boeing isn't the only company grappling with quality-control issues: RTX Corp. is recalling a significant chunk of in-service geared turbofan jet engines for accelerated and enhanced inspections after discovering microscopic contaminants in powder metal materials that can shorten the lifespan of certain parts. The Leap engine produced by General Electric Co. and Safran SA through the CFM International joint venture has had its own hiccups, including fuel-nozzle coking and distressed blades, although these issues are on a much more manageable scale. Taking the pressure off suppliers to ramp up output for Boeing Max jets could provide a much needed opportunity for stabilization — and hopefully, some introspection at Boeing on what a healthy aerospace supply chain should look like. Calhoun is taking accountability for the latest Max problem and saying all of the right things about the need for a thorough review. This is a welcome contrast to the first Max crisis, when Boeing pointed the finger at just about everyone but itself and repeatedly attempted to set its own timeline for the plane's return, to the chagrin of the FAA. The National Transportation Safety Board is still investigating the Alaska Airlines incident, and companies are legally precluded from making comments that might front-run any findings. "Whatever conclusions are reached, Boeing is accountable for what happened. Whatever the specific cause of the accident might turn out to be, an event like this simply must not happen on an airplane that leaves one of our factories," Calhoun said on the call with analysts. "We caused the problem, and we understand that." But actions that prevented this problem from happening in the first place would have meant a lot more than the right words after the fact.  It's in literally everyone's interest that Boeing figures this out — and that includes its archrival Airbus SE. Doubts about safety are to the detriment of the entire aerospace ecosystem. Boeing seems to understand that. The question is whether the company can finally make the kind of cultural and factory floor changes that would prevent the Max from having yet more safety problems. "It's a change in the way we work. So as volume returns to the system, we don't expect these jobs to come back." — United Parcel Service Inc. CFO Brian Newman Newman made the comments on UPS' earnings call this week after the parcel delivery giant announced it would cut 12,000 management jobs. UPS also plans to end pandemic-era work-from-home policies and bring workers back to the office five days a week. "This is really about a new way of working," CEO Carol Tomé said. She didn't specify what that actually means but laid out various examples of how the company is deploying artificial intelligence and machine learning to cut middlemen out of the process and improve efficiency. UPS is just the latest industrial company to announce job cuts focused on white-collar workers. Boeing said last year that it would cut 2,000 finance and human resources jobs even as it hired 10,000 workers for engineering and factory-floor roles. Norfolk Southern Corp. announced last week that it was culling 7% of its nonunion workforce, with the cuts focused on administrative staff and management. In the past, so-called craft workers — those responsible for actually manufacturing goods, running the railroads and delivering packages — were among the first to get the boot when the economic backdrop soured. That's changed. The pandemic exacerbated long-standing recruitment challenges for industrial companies, sending many scrambling to rebuild their workforces as demand boomeranged. Companies had to dangle higher salaries to get workers to apply and then pay to train them. Even as shipping logjams and parts shortages have eased, many industrial companies are less productive than they would like to be, in part because a good number of their employees are still relatively inexperienced. No industrial company wants to give up its hard-earned gains in the factory-floor labor pool, particularly should the current downturn prove relatively shallow, but the higher costs are harder to bear when business is slow.  UPS' forecast for 2024 revenue came in well short of analysts' expectations. The Institute for Supply Management's benchmark gauge of US manufacturing activity is in its longest stretch of contraction since the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s. Industrial executives expect full-time employment to increase 0.6% on average over the next year, according to the National Association of Manufacturers' fourth-quarter survey. That is the weakest outlook since the second quarter of 2020 — the peak of Covid lockdowns — and the lowest reading since the third quarter of 2016, excluding the pandemic. But only about 18% of respondents were expecting a decrease in full-time employment. Companies continued to rank attracting and retaining a high-quality workforce as their biggest business challenge ahead of a weaker domestic economy and an unfavorable tax and regulatory climate. If costs need to get cut, the guy in the suit is easier to replace these days than the one on the factory floor. Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. CEO Lourenco Goncalves doesn't in fact congratulate United States Steel Corp. on its pending $14.9 billion sale to Nippon Steel Corp. nor does he "wish them luck in closing the transaction." Cleveland-Cliffs was also trying to buy US Steel, but Goncalves' comments — made soon after the tie-up between US Steel and Nippon Steel was announced in mid-December — indicated that the company was moving on. Cleveland-Cliffs took a different tune on its earnings call this week: "Rather than working toward a deal with Cliffs, US Steel chose to announce a proposed sale of the company to a foreign buyer with serious conflicts of interest for America, no support or even awareness from the union and for a lower overall value," CFO Celso Goncalves, Lourenco's son, said. The senior Goncalves lambasted US Steel for underestimating political pushback to a foreign takeover, adding that "we do not believe that the final chapter of this story has been written." Cleveland-Cliffs — which identified itself as the Company D discussed in US Steel's official proxy filing — offered a mix of cash and stock worth $54 a share, plus potential synergy benefits of $6.50, in its final proposal and agreed to a $1.5 billion reverse termination fee. Nippon agreed to a purchase price of $55 a share in cash and a breakup fee of $565 million. But US Steel concluded that a combination with its US rival posed too much antitrust risk. Read more: US Steel-Nippon Deal to Test 'Buy American': Brooke Sutherland

Johnson Controls International Plc said it was in the early stages of evaluating strategic options for its noncommercial businesses. Bloomberg News had reported earlier that the company was exploring a sale of the bulk of its York heating, ventilation and air-conditioning operations, as well as a 60% stake in a joint venture operated with a subsidiary of Japan's Hitachi Ltd. and the Air Distribution Technologies business that it acquired for $1.6 billion in 2014. Johnson Controls CEO George Oliver declined to provide specifics about what particular assets could be divested, saying only that the parts of the company that sell products to other businesses have a different path to the market than its residential offerings. Should the company ultimately divest all of the assets reportedly under consideration, there would likely be a separate buyer for each one. Lennox International Inc. would be the most obvious acquirer of Johnson Controls' US residential products operations. But consolidation in this market may attract antitrust scrutiny, particularly in light of significant price increases in recent years as manufacturers passed through cost inflation to consumers, Wolfe Research analyst Nigel Coe notged. While the York US residential business is arguably sub-scale, it's not clear that selling HVAC assets would help Johnson Controls' languishing stock valuation. Doing so would make the company more focused on other building products, such as smoke alarms and security systems, which tend to be lower growth and lower margin, said Barclays Plc analyst Julian Mitchell. JetBlue Airways Corp. and Spirit Airlines Inc. filed a request for an expedited appeal of a judge's ruling against their $7.6 billion merger, but the acquirer also says it's evaluating options to walk away. US District Judge William Young earlier this month sided with the Justice Department in its efforts to block the airline combination on antitrust grounds, triggering a sharp selloff in Spirit shares and an open debate about its future. Under the merger agreement, JetBlue agreed to use "reasonable best efforts" to obtain regulatory approval for the deal, including appealing proceedings against the deal. Should JetBlue abandon the takeover, it will owe Spirit shareholders a $400 million breakup fee, minus prepayments of the purchase price that have already been distributed, and an additional $70 million to Spirit the company. That may be a price worth paying. The deal was meant to provide JetBlue a path toward accelerated growth through a slew of extra aircraft and staff, but that's the last thing the airline currently needs. JetBlue separately said this week that it was deferring $2.5 billion of planned aircraft capital expenditures to ease the strain on its balance sheet and was making deeper cost cuts across its business, including selling off some real estate and offering buyouts to employees. Revenue could fall as much as 9% in the first quarter while costs excluding fuel are set to rise as much as 11%. |

No comments:

Post a Comment