| After that perhaps misleading headline, let me stress that the recession I'm talking about is in the profits made by companies in the S&P 500. After three quarters of year-on-year declines, they've plainly grown in the third quarter. Wall Street is confident that this will continue. This chart from UBS shows it clearly enough: No wonder then that David Lefkowitz of UBS proclaimed: "It's clear to us that the earnings recession is over." That, however, raises a sticky issue. The corporate sector is not America's economy. But the two are closely related. How can it be that gross domestic product is still showing year-on-year growth despite everything the Federal Reserve has thrown at it, while profits have had their recession and are recovering? Lefkowitz points to one clear distinction. "Unlike GDP, S&P 500 profits skew more towards goods rather than services, so a rebound in goods activity should support earnings going forward," he said. That plainly depends in part on the health of consumer spending, but of late their enthusiasm to keep buying big-ticket items like washing machines has been impressive. Another explanation is that companies, unlike the economy at least in the short term, benefit from cost cuts. "The economy is cooling, but companies have had their earnings recession, have cut costs, and are now enjoying margin expansion," says Savita Subramanian of Bank of America. So corporate actions in doing what's necessary to safeguard profits, which fascinatingly haven't included significant job cuts, will contribute to the downward pressure on economic growth. Beyond that, Subramanian points out that profits still look pretty bad given the apparent health of the economy, largely due to the pandemic's continuing aftereffects on buying behavior: Earnings lagged GDP growth for the fifth straight quarter (historically, quarterly earnings outpaced GDP by 1.5 percentage points on average since 1950). The lag was partly due to the shift from goods (50% of earnings vs. 30% of economy) to services, which appears to be long in the tooth.

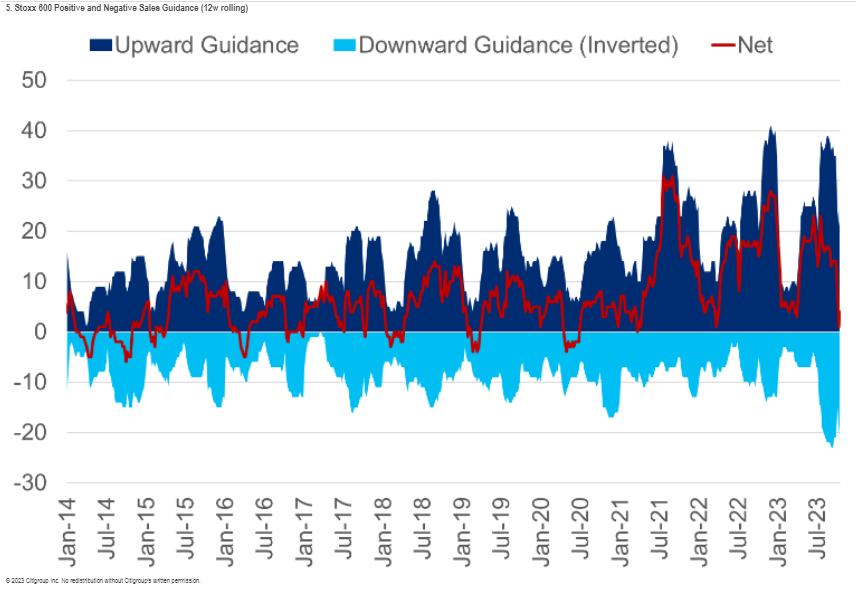

If there's a fly in the ointment, it's that expectations for both sales and earnings have been cut back sharply for the current quarter, even as the numbers for the last period came in well ahead of expectations. Andrew Lapthorne, quantitative strategist at Societe Generale SA, illustrates this: But not too much should be made of this as roughly half the decline, Subramanian says, is due to "idiosyncratic" problems for two pharmaceutical companies, Pfizer Inc. and Merck & Co. Demand for Covid vaccines and other associated drugs is much weaker than expected. A significant economic downturn, not something factored into most sell-side analysts' spreadsheets, would change things. But as it stands, the corporate world tends to contradict the judgment of the bond market that the economy is slowing down rapidly. What else has the earnings season told us? Investment banks can now use "big data" tools to mine call transcripts for trends, and an obvious one is the rise in "reshoring" — bringing offshore jobs and production capacity back to the US (or at least much closer, like Mexico). This is a practice that dents profits in the short run, and may also increase inflation, but that should drive longer-term domestic growth by boosting investment: Meanwhile, if there's one thing that preoccupies chief executives, it's financing costs: It's good to know that monetary policy appears to be taking effect, and the implication is that higher interest costs will eat into profits. At present, particularly after the surge of excitement that peak rates have been reached, the belief is evidently that companies can still make money despite the higher interest burden. Let's hope that's right. Europe's economy is leading the US in apparently already lapsing into recession. Meanwhile, its corporate sector is a long way behind the US, and is only now falling into an earnings recession. Third-quarter profits announcement are on course for the first year-on-year decline since the pandemic year of 2020. Even if the energy and materials sectors, greatly buffeted by turbulent commodity prices, are excluded, Bankim Chadha of Deutsche Bank AG shows that Europe's companies have been sharply worse than the rest of the world: One major contributor to this is that European companies weren't able to raise their margins in the third quarter, unlike their counterparts in the US, Japan or the emerging markets: Failure to make greater sales has done even more damage to the bottom line. While the problems for the European economy are known, the corporate sector's problems came as a nasty surprise. The greatest (if perverse) reason for hope may be that companies also chose in greater numbers than at any point in the last decade to downgrade their guidance for future sales. With any luck, the bad news is now in the price. The number upgrading revenue forecasts is also high, but as this chart from Citi's Beata Manthey demonstrates, overall this is the most downbeat European companies have been about the future since the pandemic:  As for European share prices, the impressive pickup they enjoyed compared to the US around the market trough of October last year has gone, almost entirely. The FTSE EuroFirst 300 index has now surrendered all its gains relative to the S&P 500 of the last 12 months. But it's notable that the US "Magnificent Seven" of big internet platform companies seem to be central to this; compared to the equal-weighted version of the S&P 500, in which mega-cap stocks are far less influential, Europe has not given up new ground over the last couple of months:  As for valuations, Europe continues to look cheaper than the US, as it has for many years now. The following chart, available from Barclays' handy website, gives their estimates of the cyclically adjusted price/earnings (CAPE) multiples for MSCI's Europe and US indexes. This shows the ratio of price to inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous 10 years. Until the Global Financial Crisis, Europe traded at much the same valuation as the US, despite its relative lack of tech companies commanding higher multiples. It's since settled into a pattern of being much cheaper: It's possible that valuations at last account for all the bad news about future earnings, and Europe's cheapness gives investors a better cushion than they get when investing in the S&P 500. But it's been possible to say that for a decade now, and Europe still underperforms. Environmental, Social and Governance investing is now part of the culture war. Inflated claims made by its backers have now been matched by equally overblown attacks by critics. To this depressing spectacle, we have a genuinely new contribution from New York University. I doubt that it will help resolve the debate, but it deserves to be listened to. The core idea in Making ESG Real: A Return to Values-Based Investing, authored by Michael Goldhaber, senior research scholar at NYU Stern's Center for Business and Human Rights, is to admit upfront that values matter, and if necessary outweigh attempts to maximize return. At present, ESG investors use screens for the different factors, while arguing that these factors will help investments to outperform in the longer term. For example, it seems a reasonable contention that companies that have their emissions under control and are ready for energy transition might well benefit from this in future. Plenty of research when ESG was gaining critical weight a decade ago suggested that investors could "have their cake and eat it" — both do good, and outperform. As long as it can be presented as a systematic attempt to beat the market, like other factoral investing, it could be marketed effectively. Goldhaber's criticism is that companies can do things that badly affect the environment but do no damage to their bottom line. For example, the ESG rating of McDonald's has improved as it adopts recyclable packaging — and yet it's still responsible for huge herds of methane-producing cattle. ESG currently measures "how environmental and social risks may harm shareholders, rather than how business may harm the world," according to the NYU report. Often, as in the McDonald's example, firms can harm society without any negative consequences for shareholders, while the costs of ESG monitoring create extra costs that make good investment performance harder to achieve. To deal with this, funds should embrace the idea that they are going to improve the world, and accept that this may mean taking action against things that don't directly hurt them as shareholders. At a more nitty-gritty level, Goldhaber argues that regulators should require much more transparency on ESG issues from companies in a standardized format. Conservative critics object to this for reasons that are unclear. He also advocated giving up on the attempt to produce one single "ESG" rating that smooshes together all measures in all three categories. Companies could be judged against absolute standards rather than compared in rankings (which can mean rewarding mediocre performance or punishing companies that have been responsible). Funds themselves should be unabashed about exactly what they're trying to achieve, and use exclusions to help do it. This would ensure that the unwary didn't end up investing in companies of which they disapproved, while the more limited and precise goals would be easier to achieve. Rather than an additional label on a mass-marketed fund, the actual ESG aims themselves would become part of the competition for clients.  Better packaging, but where's the beef? Photographer: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg "The ESG investment community should resist the mindless attacks from the right," says Goldhaber. "But it should stop ignoring the valid critiques pouring in from regulators, academics and practitioners who have no political agenda. ESG investing is broken, and we are issuing a constructive call to fix it." At an intellectual or principled level, I cannot disagree. Should people (such as, it would appear, very many millennials and members of Generation Z) want to invest on the basis of reducing harm to the environment, in full knowledge that this won't necessarily net them the highest returns, then they should be allowed to do so. Funds with these aims would have a better chance of doing some good than the current range of ESG products. At a practical level, I doubt that it will help. People like me (who once majored in both philosophy and economics) find this fascinating. Others will find the discussion rather fatuous. In terms of politics, the debate is so utterly ill-informed, carried out in a childish way meant to turn investment choices into yet another front in the culture war, that these reforms would make no difference. A large proportion of the US population has decided that anything ESG is illegitimate on its face, and that won't change. Perhaps most importantly, there is the fact that individuals would have to sign up to invest in a way that might not net them the best returns. That is as it should be. People have a right to make this choice, but nobody has the right to impose it on them. The problem is that this is going to be a much harder job for fund managers' marketing departments. In the US, there's also the issue that existing pension law makes it hard even to offer such a fund (even though plenty of the options on offer from the average 401k will probably do worse at some point). But in general, it's going to be hard to build up such funds to a weight where they can really affect the world, let alone make it better. This is to alert you to the latest publishing phenomenon that Points of Return readers will need to know about. The Fund, by Rob Copeland has just been been released and sets out to do for Bridgewater Associates, the world's biggest hedge fund, what Michael Lewis's Liar's Poker did a generation ago to the bond-trading department at Salomon Brothers that then dominated Wall Street. Lewis made his reputation with a brilliant book about the testosterone-fueled bear pit in which he worked, and The Fund, judging by the excerpts and reviews so far, appears to be both as critical and as funny.  Ray Dalio during the Bloomberg Invest event in New York in June. Photographer: Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg According to the New York Times's review, it portrays Ray Dalio, the investor and author who built up Bridgewater to its current prominence, as presiding over a "manipulative professional hellscape." In an excerpt that has appeared in Vanity Fair, Copeland tells the story of how the fund once employed James Comey, famous for leading the FBI, on a $7 million salary. In this piece for the New York Times, Copeland attempts a stronger critique of its investment record. In another adapted excerpt in Business Insider, Copeland tells us that Dalio once drove a pregnant employee to tears. And you can read the inimitable opinion of our own Matt Levine here. To be clear, I'm not judging the book because I haven't read it. And as many traders tell me they were inspired to take up their career by Liar's Poker, it might perversely help Bridgewater's reputation. The fund's success in generating returns will limit damage to its reputation, and a response from Dalio and Bridgewater's senior management should be mighty interesting. But after a literary hand grenade like this, it's best to brace for the aftershocks to last for a while.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment