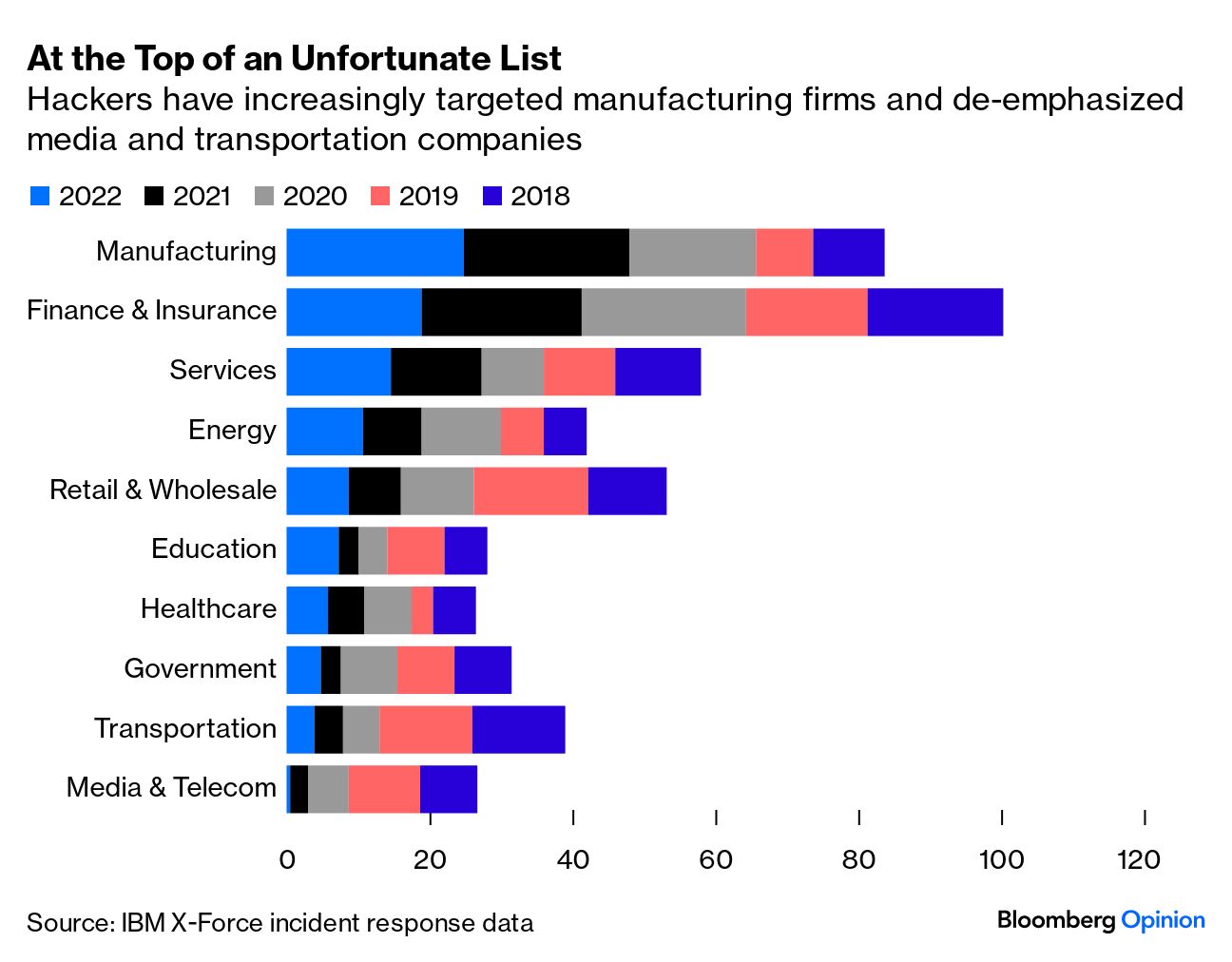

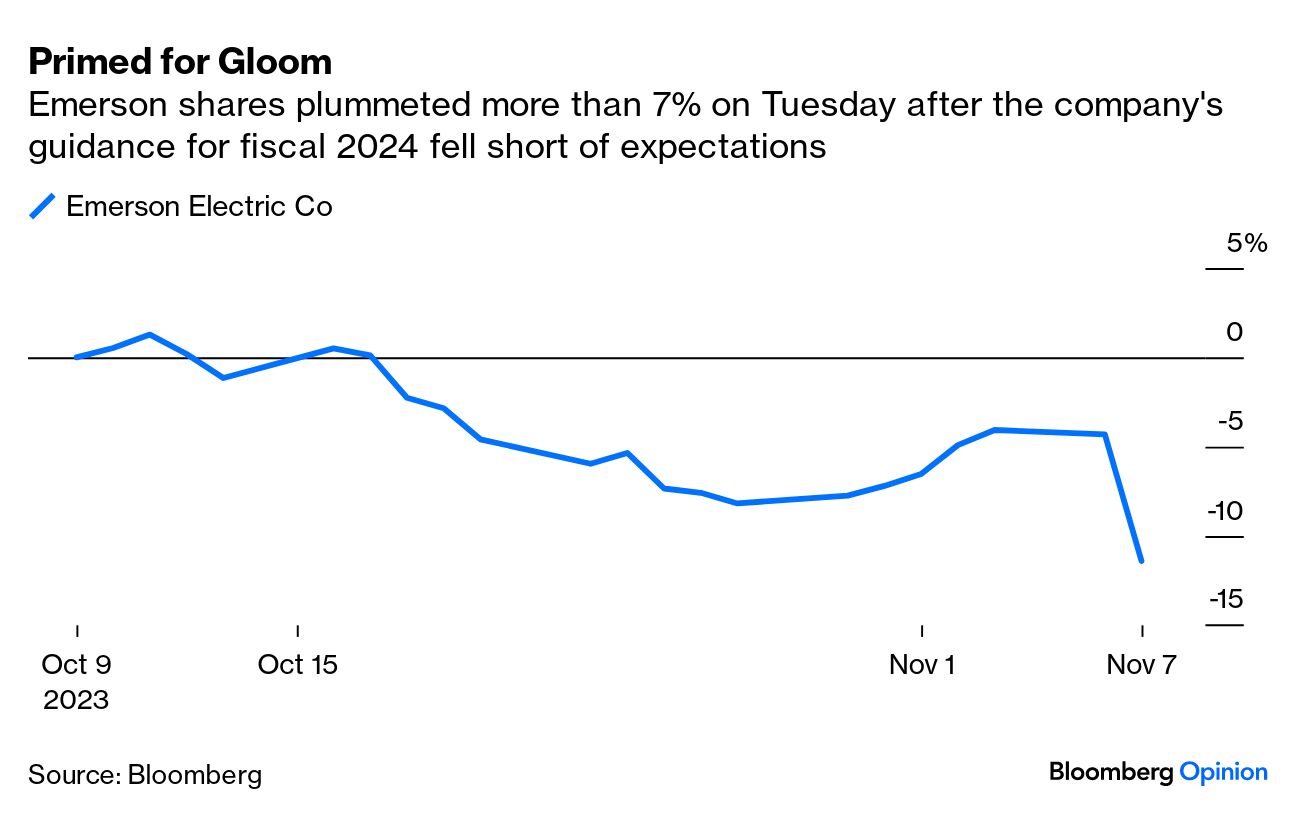

| Have thoughts or feedback? Anything I missed this week? Email me at bsutherland7@bloomberg.net An unnerving number of large US industrial companies have been hacked this year. Johnson Controls International Plc, a heating, air-conditioning and fire-safety systems company, and Mueller Water Products Inc., a maker of fire hydrants, butterfly valves and leak detection technology, have both delayed the release of their latest quarterly results because of lingering disruptions from cyberattacks. Meanwhile, Fortive Corp., which makes test and measurement tools and asset management software, flagged a $5 million one-time expense related to remediating a breach of its network infrastructure in early October that caused some downtime at certain North American facilities. A June cyberattack cost boatmaker Brunswick Corp. as much as $85 million of revenue in the second quarter because of lost production days, particularly in the engine division. Power-transmission company Gates Industrial Corp., compressor giant Ingersoll Rand Inc. and gold and copper miner Freeport-McMoRan Inc. also experienced cyberattacks this year. The collective market value of these companies is almost $150 billion, and they generate a combined $75 billion in annual revenue.  Manufacturers were the most targeted industry for cyberattacks in 2022 and 2021, according to a report from International Business Machines Corp.'s X-Force cybersecurity group. That marked a change from the previous five years, when the financial and insurance sector experienced the highest percentage of hacks. The growing rate of cyberattacks at industrial companies — which can range from ransomware demands for money to the exposure of confidential data — to some extent reflects a surge of investment in digital connectivity. Dumb hunks of metal are rare these days; just about every piece of equipment is loaded with data-collecting sensors and layers of software. This became painfully apparent during the semiconductor shortage, which affected everything from electronic cigarette manufacturing to Caterpillar Inc. excavators. But if everything is connected, then everything is vulnerable. There's no longer a natural protective moat separating an industrial company's core production operations from the IT system, so a cyberattack has the potential to be much more disruptive (and much more lucrative from the hackers' point of view). As companies "have gone through the journey of making their operations more connected to the cloud, it has just increased the risk profile," Tim Gaus, a principal at Deloitte and the leader of its smart manufacturing business, said in an interview. "Some people weren't aware of how much the risk profile shifted." More than 80% of hacks affecting industrial operations originated with compromised IT systems, and attackers are also increasingly targeting internet-linked human-machine interfaces and engineering workstation applications, according to an analysis of 122 attacks by Rockwell Automation Inc. and the Cyentia Institute, a cybersecurity research firm. Time has always been money for industrial operators. In fact, one reason manufacturers have sought to connect machinery of all shapes and sizes to the internet in the first place is the pursuit of a technological edge that could help them predict and avoid costly time-consuming breakdowns in key equipment. The consequences of forced, unexpected downtime may make manufacturers more likely to pay a ransom than, say, a data-center operator that can draw on backups for essential files. Successful cyberattacks beget more cyberattacks. It's unclear whether any of the large industrial companies targeted this year have in fact paid ransoms. "Boy, I tell you, this is annoying. I hope your companies never have to deal with it," Freeport-McMoRan Chief Executive Officer Richard Adkerson said at a conference in September. "These are just common crooks and they just try to put you in a corner and make you do something. We're fighting it so far successfully."  Even as manufacturing hacks have become more prevalent, I can't remember when so many large, publicly traded industrial companies have disclosed attacks. Johnson Controls appears to be one of the most seriously impacted. A cyberattack on its internal information technology infrastructure spared many applications, and Johnson Controls is installing workarounds where possible to continue servicing customers, but "the incident has caused, and is expected to continue to cause, disruption to parts of the company's business operations," according to a late September statement. Johnson Controls hasn't made any kind of public comments on the matter since then — nor has it provided an official date for when its earnings might finally be released. Historically, that would have happened around this week. "We know not when JCI will report (and perhaps neither do they)," Wolfe Research analyst Nigel Coe wrote in a note. A spokesperson for Johnson Controls said the company had no further update at this time. The building products manufacturer operates on a fiscal year that ends in September, meaning the attack took place toward the end of its most important quarter. Johnson Controls is also a government contractor. CNN reported in September that the Department of Homeland Security was investigating whether sensitive information — including facility floor plans and other details about buildings' security systems — might have been compromised in the ransomware attack. At Mueller Water, the cyberattack affected certain operational and information technology systems — including those needed to finalize its fiscal 2023 financial statements. Still, the company was able to release preliminary figures for sales, adjusted profits and the balance sheet. Plenty of manufacturers now see themselves as technology whizzes. It's a sales pitch that has tended to fall flat with investors, who generally still value industrial companies like industrial companies. But there's arguably no greater evidence that a transition is indeed taking place in the sector than the increasing attractiveness of these kinds of targets to hackers. If industrial companies want to be technology companies, then they need to think like them when it comes to protecting themselves against cyberattacks. Rockwell Automation this week completed its acquisition of Verve Industrial Production, a cybersecurity software and services company that focuses on industrial environments. Verve's key product offering is an asset-inventory system that recognizes all industrial equipment, regardless of manufacturer, and assesses potential pain points. The idea is to provide more visibility into what's often a hodgepodge of legacy systems and next-generation hardware and software on the factory floor. It's very expensive — and extremely impractical — to update an entire facility worth of equipment at the same time, let alone a global network of plants. So you end up with situations where even a technologically forward-thinking industrial company might still have a piece of equipment connected to a dial-up connection, for example. Understanding where the potential vulnerabilities are is a crucial first step in cybersecurity preparedness, but the issue often isn't the underlying technology infrastructure — it's the employees. Phishing has long been the primary pathway for hackers to gain initial access to a system, and this remained the case in 2022, according to the IBM report. "The education that's required at all levels is a bit different when you connect to the digital world," and that extends all the way down to hourly workers, Gaus of Deloitte said.  Emerson Electric Co. closed out the industrial earnings season this week with a bang — but not in a good way. It was the automation company's worst share performance on an earnings day since at least 2013, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. At the peak of the selloff, Emerson shares were down 9.4% — the worst intraday slide since March 2020 amid the pandemic market panic. The numbers were far from dismal: Emerson expects to grow sales 4% to 6% on an organic basis in fiscal 2024 as continued strong performance for its process and hybrid automation businesses is offset by a slump in sales of its discrete offerings. Discrete manufacturing deals with distinct, countable items such as appliances or cars on a factory assembly line, while process automation focuses on products produced in batches, such as chemicals or oil derivatives, and hybrid involves a blending of the two approaches in the same environment for goods like laundry detergent or bottles of shampoo. Underlying revenue for the discrete automation business slumped 8% in the three months ended in September relative to the period a year earlier. Orders in this business have been negative for several quarters, but the company expects this trendline to flatten and turn positive in the second half of fiscal 2024. Emerson completed the $8.2 billion acquisition of test and measurement company National Instruments Corp. in October. Emerson isn't alone in seeing a slowdown: ABB Ltd. said orders declined 27% in its robotics and discrete automation business in the third quarter amid weak demand in China and a pullback in bookings from machine builders as they work through inventory accumulated during the post-pandemic supply chain disruptions. Rockwell exited 2023 with a lower backlog than forecast and the midpoint of its organic sales growth guidance suggests just a 1% boost next year. The weaker-than-expected orders intake reflected the absence of outsized advance bookings that were common during the peak of supply-chain disruptions, Rockwell CEO Blake Moret said in an interview. "Lead times have improved and they don't have to place those orders," he said. But in conversations with needle-moving customers, the "overwhelming majority are planning to increase investment over the coming year." Emerson CEO Lal Karsanbhai was more blunt about the pressures in the discrete automation market: This is "demand-driven weakness ... it's not a destocking element," he said, referring to a phenomenon in which distributors whittle down a glut of existing inventory rather than place new orders. "It's global weakness across the key markets. Now, having said that, the comparables do get easier as we get into the second half. We're not counting on underlying demand conditions in the discrete market significantly improving in the second half." On the other hand, Karsanbhai said Emerson's process automation operations should be more resilient in the face of macroeconomic malaise because of domestic capacity investments in life sciences and mining, a global emphasis on energy security and the transition to more sustainable power sources. Read more: Cracks Emerge in Manufacturing Boom Many CEOs who have made similar arguments about a decoupling of the industrial sector from economic cycles are among those who reported a slowdown in activity in the most recent quarter. The reality may be more nebulous: As I wrote last month, it's possible that these secular forces — the energy transition, nearshoring, government stimulus and the return of national industrial policy — are both real and meaningful over the long term and subject to macroeconomic ebbs and flows in the short term. There's been less of a boom in capital spending to date on process and hybrid automation, which means there's less room for a correction. But historically, these markets have tended to follow discrete automation into a slowdown with a lag of about a year. "This time is probably not different," Barclays Plc analyst Julian Mitchell wrote in a note. GFL Environmental Inc., a Canadian trash hauler, should sell itself or divest additional assets to help chip away at its inflated debt load, according to investor ADW Capital Management LLC. "We believe GFL is an extremely valuable company that the public markets are unable to appreciate today and perhaps never will be able to," ADW founder Adam Wyden wrote in a letter to the company's board. While a higher interest-rate environment increases scrutiny of highly leveraged companies such as GFL, the persistence of elevated financing costs suggests stubborn inflation, which tends to translate into meaningful pricing power for the waste-management industry, Wyden wrote. GFL went public in 2020. The Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan and private equity firm BC Partners hold about 26% of the company's stock between them, a legacy of a 2018 recapitalization, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. GFL is a highly acquisitive company and a public share price is useful currency, so that may undercut the rationale for going private, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Scott Levine writes in a note.

Ryanair Holdings Plc is making so much money from cramming passengers into planes like sardines that the airline can now afford a regular dividend payment to shareholders. The carrier plans to distribute €400 million ($430 million) to investors in its maiden payout next year — an amount equal to what was raised in a 2020 equity offering that helped the company bolster its balance sheet at the height of the pandemic. "We're delighted this morning now to be able to effectively refund that," Chief Financial Officer Neil Sorahan said in an interview this week with Bloomberg Television. In subsequent years, Ryanair intends to distribute 25% of its post-tax annual profit to investors as a dividend while also retaining the option to make special additional payouts and conduct share buybacks. "The bearish interpretation of announcing a regular dividend is that the carrier's high-growth days are over," writes Bloomberg Opinion's Chris Bryant. Ryanair would be expanding more aggressively if it could, but persistent delays in deliveries of Boeing Co. aircraft have forced the airline to recalibrate. As many as 10 of the 57 Boeing 737 Max planes that Ryanair had expected to have in time for the 2024 summer travel season might be delayed until the winter of next year, the airline said. Separately, Steven Udvar-Hazy, founder and chairman of plane lessor Air Lease Corp., said Boeing and Airbus SE are both unlikely to meet their delivery targets for 2023 as the manufacturers deal with quality-control issues elsewhere in their supply chains. Spirit AeroSystems Holdings Inc. announced a $200 million equity offering and the issuance of another $200 million in senior notes maturing in 2028 to raise funds for "general corporate purposes." As is common with equity raises, this maneuver didn't go over particularly well with Spirit shareholders: The stock fell as much as 15% on Wednesday. But it's probably the right thing for Spirit to do. The company has been the source of not one but two quality-control issues this year that have stunted deliveries of Boeing's 737 Max, with the latest issue involving improperly drilled fastener holes that are proving particularly time-consuming to fix. Spirit said earlier this month that it expects to burn as much as $325 million in free cash flow this year. A deal with Boeing to rejigger the terms of contracts on the 737 and 787 programs provides a lifeline, but Spirit still needs to negotiate a similar compromise with Airbus. Even then clawing its way back to profitability is no simple task. |

No comments:

Post a Comment