| For a period in the summer, mountaineering took over the monetary policy debate. Should rates reach a certain level and stay at that plateau for a while (Table Mountain), or should they peak a bit higher and then come down more steeply (the Matterhorn)? The point is that for mountaineers, for myriad reasons, the climb down is much more dangerous than the ascent. People are tired, their concentration is wavering, and the adrenaline is gone. Indeed, several of the first climbing team to ascend the Matterhorn died during the descent. A lengthy plateau like South Africa's Table Mountain sounds a little safer. Now the analogy thickens. This week, I met two investors from Perspective Investment Management, whose head office is in Cape Town. They told me that contrary to appearances, Table Mountain is deadly. Helicopters circling to lift dead and injured hikers are a common and mournful sight. The park service has even warned that it kills more people than Everest, although factcheckers query that. As far as I can determine, it definitely doesn't kill as many as the Matterhorn. Some Googling suggests that more than 500 have perished on the Swiss peak in the 150 years since it was first scaled, while the official tally for Table Mountain is 251 — which is only just behind Everest's toll of 284.  There are no illusions about a casual hike on Mount Everest. Photographer: Phunjo Lama/AFP/Getty If we were to try expressing this as a rate, the South African peak would be revealed as far safer. There aren't figures for how many people make their way to the summit, but it's assuredly many multiples of the hardened alpinists who tackle the Matterhorn. The problem is that Table Mountain's flatness lures people into a false sense of security. People try scaling it in flip-flops, or without water, or when drunk, and realize too late that they're in a difficult environment. To quote from the park's website: "Table Mountain is a mountain, not a hill! Please respect and enjoy your mountain." Why is this relevant to monetary policy? Inflation is descending significantly faster than expected, and that's prompting a rethink about whether it's really necessary to take the risk of staying at a high plateau and wait for something to go wrong. That debate is particularly alive in Europe, where the latest numbers on eurozone inflation, covering November, have created a graph that looks quite a lot like the Matterhorn. It's an extreme version of the path that price rises have followed in the US: If inflation is coming down that fast, why shouldn't interest rates do the same? Indeed, might it not be safer to start the retreat as soon as possible? With an economy exhibiting much less growth than the US, as well as faster declining inflation, Dario Perkins of TSLombard comments waspishly that "it looks like the ECB succeeded in getting behind the curve twice in this 'fake cycle' – both on the upside and on the downside." Or, to quote Craig Erlam of OANDA, with the eurozone on the brink of recession: "Policymakers will have to question whether conditions are too tight based on recent evidence, almost certainly starting at the meeting in two weeks… So far, we've been told that it's not the time to even have the conversation, but surely that's no longer true."  A skier silhouetted against the Matterhorn in Breuil-Cervinia, Italy. Photographer: Marco Bertorello/AFP/Getty Others disagree. In another metaphor from mountaineering, the "last mile" can be the hardest. This fall has been faster than virtually any estimate, but there are still a couple of driving forces that will soon leave the equation. In particular, the energy crisis took inflation into double figures, and prompted governments to spend public money on comforting the blow to consumers. Michel Martinez of Societe Generale SA commented: This trend is fading, and we expect headline inflation to increase at the turn of the year because most governments will begin unwinding their energy support measures. Given our core inflation estimate and the ECB's sticky inflation forecasts, we expect the ECB to keep rates unchanged for longer than the markets do. We do not anticipate any rate cuts before end-2024 and next spring, the ECB may consider increasing Quantitative Tightening.

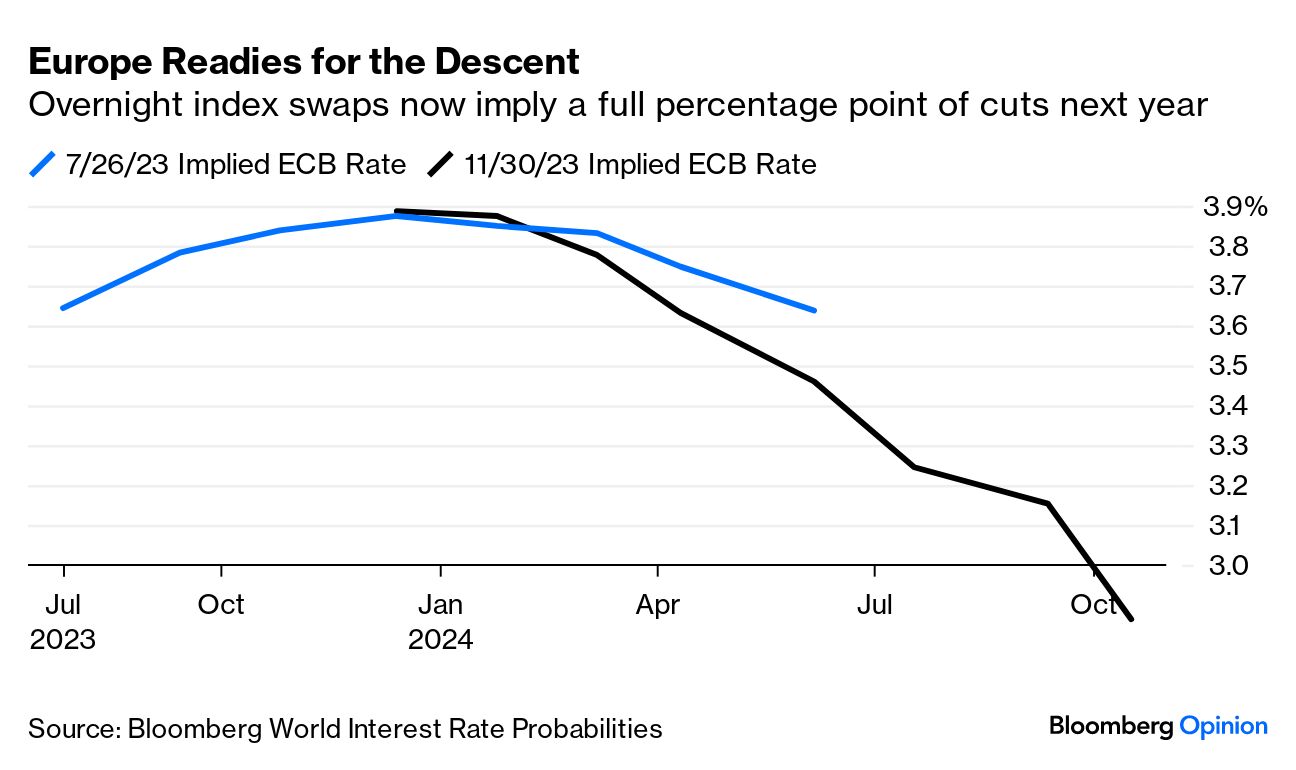

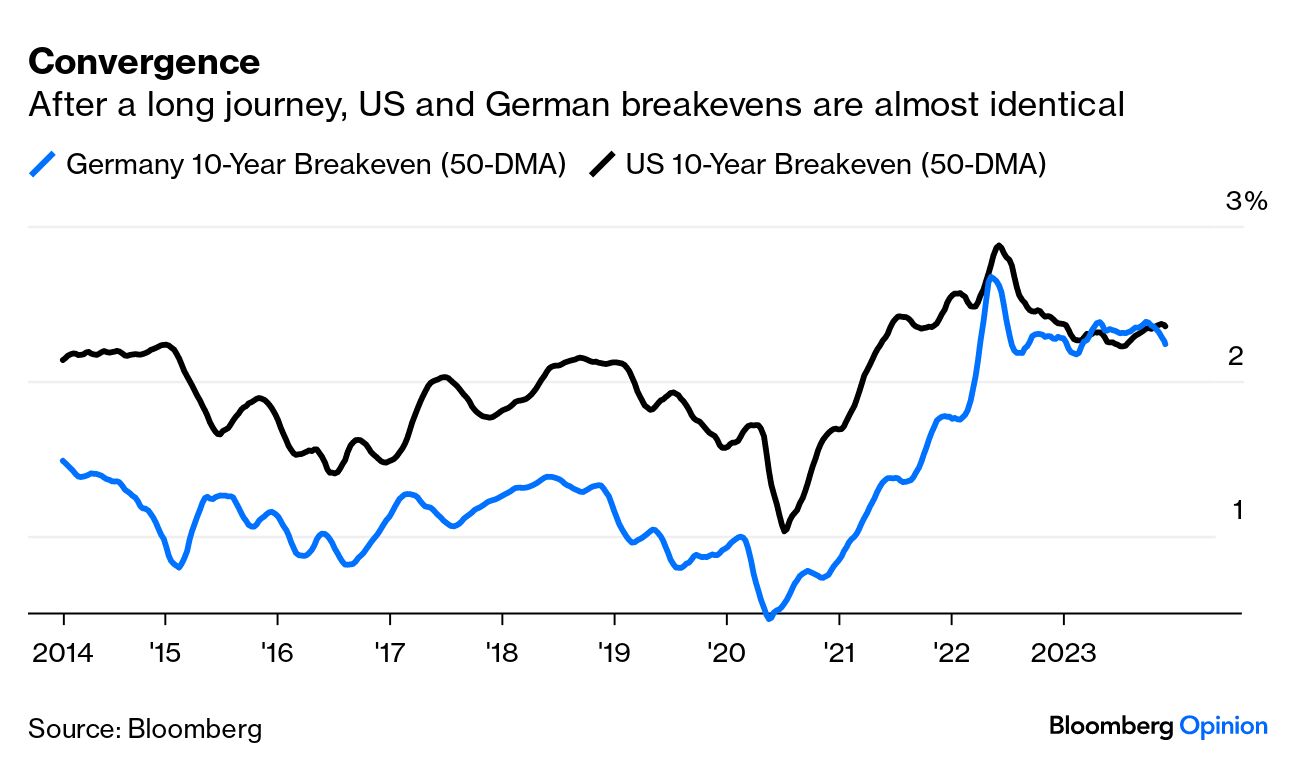

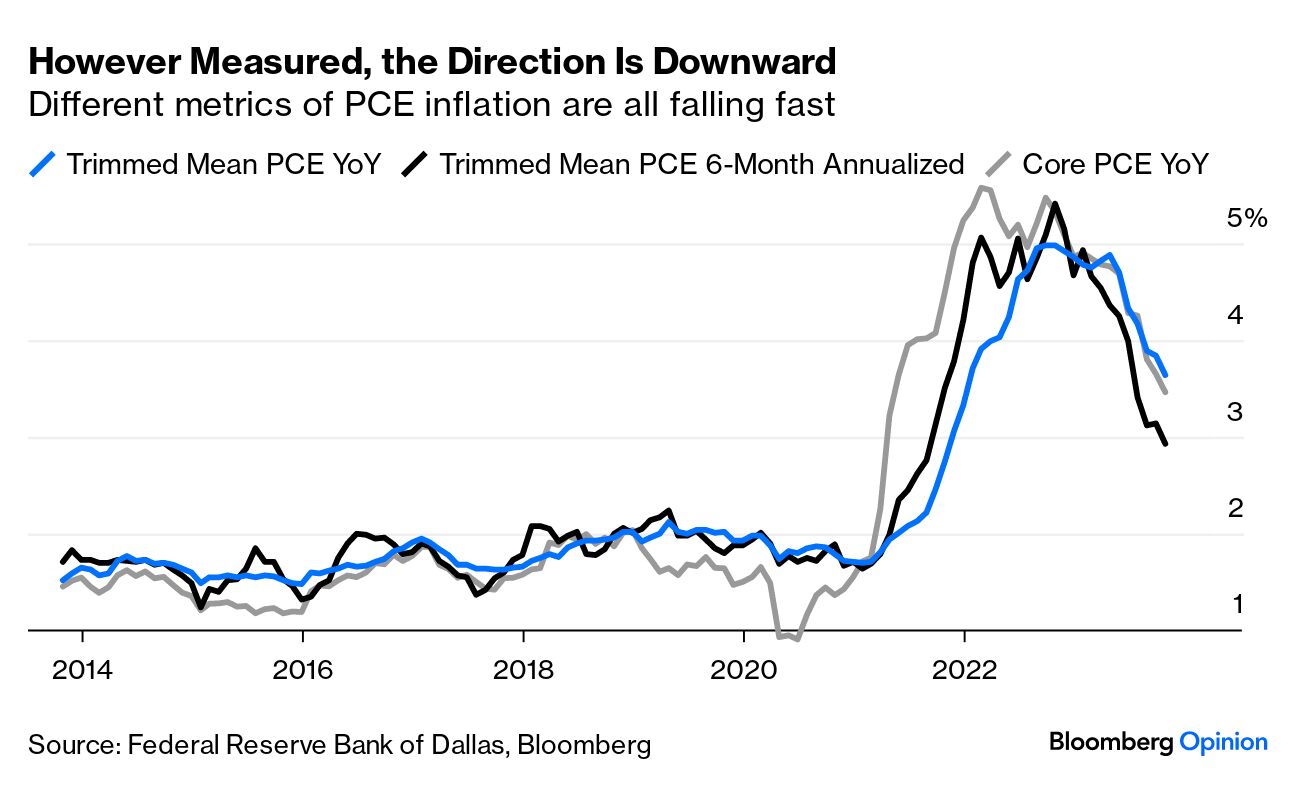

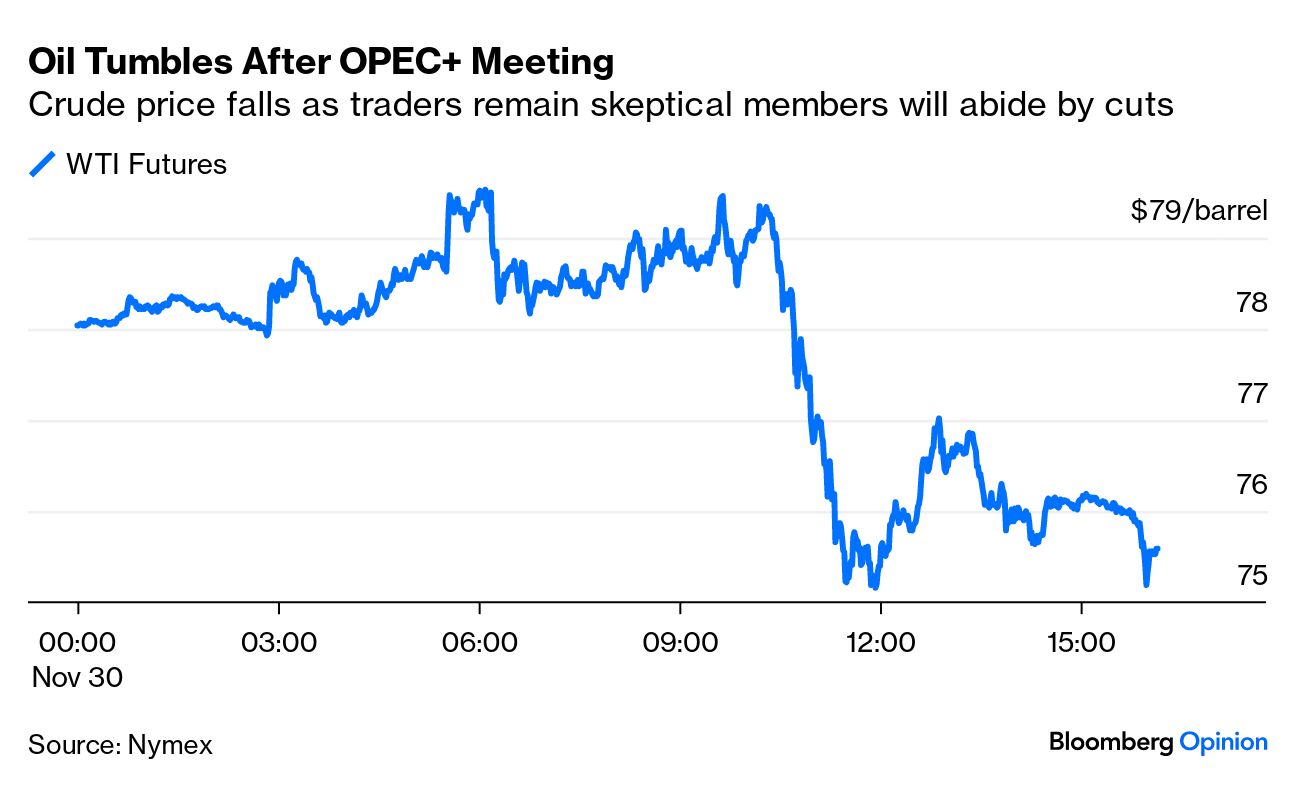

Alternatively, he suggested it could opt to raise the minimum reserves requirement ratio for banks above 1%, another move that would tighten conditions. For the time being, however, such hawkish voices are in the minority. In Europe, the notion that the central bank would stay "higher for longer" peaked in July, ahead of the Fed. Overnight index swaps show there has been a strong move to discount rate cuts since then. A full percentage point of cuts over the next 12 months is now priced in:  The pressure on the ECB can only intensify from here. In the meantime, however, the central bank can be very encouraged about what has happened to bond market inflation breakevens. For years since the eurozone's sovereign debt crisis, markets have forecast very low inflation well into the future. That spiked alarmingly higher in 2021 and 2022. Now, it's settling at a level just above the target of 2% and almost exactly in line with equivalent breakevens for the US. If the ECB can somehow keep these conditions intact, that would be a big victory — but, like a walk along the top of Table Mountain, it's as well there are potential steep drops on either side:  Meanwhile, the US also had news to support the notion that rate cuts need not be far off. Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) data for October were published. This is the Fed's favored measure of inflation, and thus matters greatly. And both the core measure and the "trimmed mean" (in which outliers are excluded and an average taken of the rest, which is much beloved of statisticians), showed continued steady declines. Over the last six months, the trimmed mean has been rising at an annualized rate of less than 3%, suggesting that the target is growing coming within range:  As in Europe, the issue will be the final mile and whether inflation can successfully get back down to 2% or below without causing an accident. It's undeniable that the descent has gone far better than expected for the last few months, which explains the startlingly strong performance of both US bonds and stocks this month. Bloomberg's own index for a global 60% stocks 40% bonds portfolio is up 8% for the month, only marginally behind November 2020, the month when surprisingly successful Covid-19 vaccine tests sparked a relief rally: It's questionable whether this month's news on prices really justifies a market reappraisal on the scale of that one. As with hikers on Table Mountain, it's well not to take this too lightly. But it's easy to understand that investors now want to convince central banks that a Matterhorn-style descent might be better after all. OPEC+ on Thursday intended to jolt markets by announcing a new oil supply cutback of about 900,000 barrels a day during an online meeting. But the organization — with members including Russia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Iraq — was left disappointed as crude prices fell. Traders, it seemed, were largely skeptical that the new plan will be implemented given that the curbs are on a "voluntary" basis. Saudi Arabia promised to continue its unilateral 1 million barrels-a-day cut through the first quarter, but oil prices plunged after investors were left underwhelmed by the smaller-than-expected cuts. The ambiguous details did not help. The chart below shows West Texas Intermediate futures erasing the day's initial gains, and then failing to put together a rally:  The meeting was already delayed four days due to a dispute over the quotas for some African members. And those extra days for persuasion don't seem to have succeeded. Angola has already rejected its new reduced target, saying it will continue pumping. As colleagues comment, the defiance brings back "troubling memories" of Ecuador's exit from the group. The South American producer said it would breach its quota in 2017, and eventually ended up leaving. That oil barely moved may be indicative of the influence — or lack of it — of OPEC+. Here are GlobalData TS Lombard strategists Hamzeh Al Gaaod and Konstantinos Venetis: These additional OPEC+ cuts extend the hawkish approach to supply which has been in place since the spring — it looks as if the cartel's aim is to push prices higher still, not just maintain a floor. But beyond any near-term bounce on this news and broader risk-on sentiment, we see the underlying balance of risks for oil deteriorating — prices are likely to face downward pressure next year.

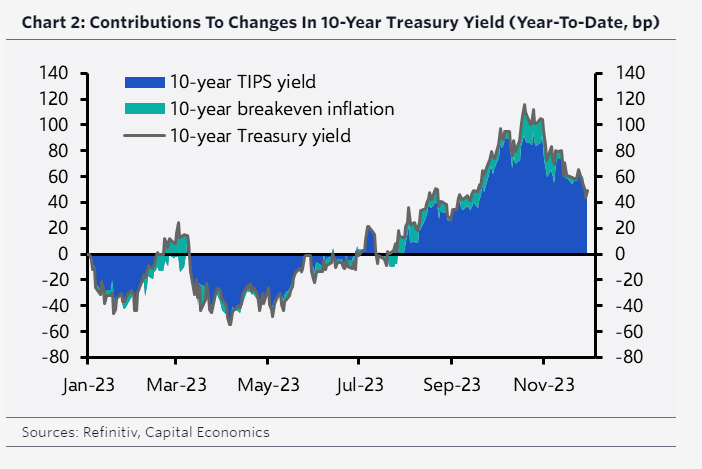

(Of note is Brazil being invited into OPEC+, though the Latin American producer won't be taking part in any production cuts. "This feeds into our theme that OPEC+ is trying to regain tight control of global oil supply as North American production peaks," said Al Gaaod and Venetis. "We expect the oil market to settle lower over the course of 2024 H1, tracing a bottom and setting the stage for a potential rally in 2024 Q3/Q4.") The move matters beyond commodities because inflation expectations are now jumping against the backdrop of more production cuts, said José Torres, senior economist at Interactive Brokers. As a result, bond yields and the US dollar rose given that higher oil prices may "incrementally delay" the Federal Reserve's path to cutting rates. That affects a higher premium for lending over the long term that investors demand, he added. To some though, like James Reilly, markets economist at Capital Economics, oil prices will continue to have little bearing on most other financial markets over the coming year. He doesn't expect Brent crude prices to move much: The fact that energy markets are dancing to their own tune is hardly something new... Admittedly, the fall in oil prices over the past two months has coincided with a huge fall in Treasury yields. But we think that is more a story of correlation than causation; after all, most of the action has come in real yields, rather than in inflation expectations.

Source: Capital Economics And indeed, the long established relationship between oil prices and market inflation breakevens hasn't had much effect of late. In theory, higher oil prices should reduce expectations for future inflation by creating a higher base. In practice, higher oil prices in the present tend to translate directly into higher inflation expectations, in large part because inflation traders tend to use oil futures as a hedge. What's interesting is that the rise and fall of the oil price over the last few months has passed with minimal impact on US short-term inflation breakevens: At a time when two separate conflicts are raging, both with the potential to bring supply of fuel down sharply, this may seem surprising. But as it stands, the oil market isn't scared of OPEC+, and other markets aren't scared of oil. — Isabelle Lee Few people were in a better position to offer tips on survival than Henry Kissinger, who passed away this week at 100. This is his obituary in my alma mater, The Financial Times. One of the writers of the obituary is Malcolm Rutherford, my colleague for nine years and one of the most distinguished journalists of his generation. He passed away in 1999, at the age of 60. This is his obituary in The Guardian. That obituary was written by Hugh O'Shaughnessy, a renowned foreign correspondent. He left us last year, at 87; this is his obituary. So Kissinger not only outlived his obituarist, he even outlasted his obituarist's obituarist. That's a survivor. And there's something curiously reassuring in the fact that Malcolm Rutherford's prose is still being published anew, almost a quarter of a century after his death. There's a kind of immortality in writing obituaries.  An old man said to me, 'Won't see another one' Photographer: Dave J Hogan/Getty Images Europe For an arguably even greater survivor, try Shane MacGowan, the lead singer of The Pogues, who has just left us at 65. Given his epic, life-long campaign of self-described self-abuse, that was an achievement in longevity to rival Kissinger's. His obituaries in The Guardian, Pitchfork and The Washington Post make great reading because he had an extraordinary life. The most amazing fact to arise from them, for me, is that he was born in Tunbridge Wells, one of the leafiest and nicest towns in southeast England, and went from there to the highly prestigious Westminster School (where he found his true calling and was expelled). That he was English is not what I would have expected from a man whose whiskey-and-cigarette-rasped songs embodied an edgy kind of Irishness. He was a wonderful and distinctive musician who hardened the mist on traditional Irish music and brought it to a broad and new audience. This isn't exactly an original choice, but you might want to listen to Fairytale of New York. It's so well known because it's a masterpiece. A little further off the beaten track, you could try Body of an American, Sally MacLennane, or Dark Streets of London. Rest in peace, Shane MacGowan, and the other illustrious people who left us this week. And have a great weekend everyone.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment