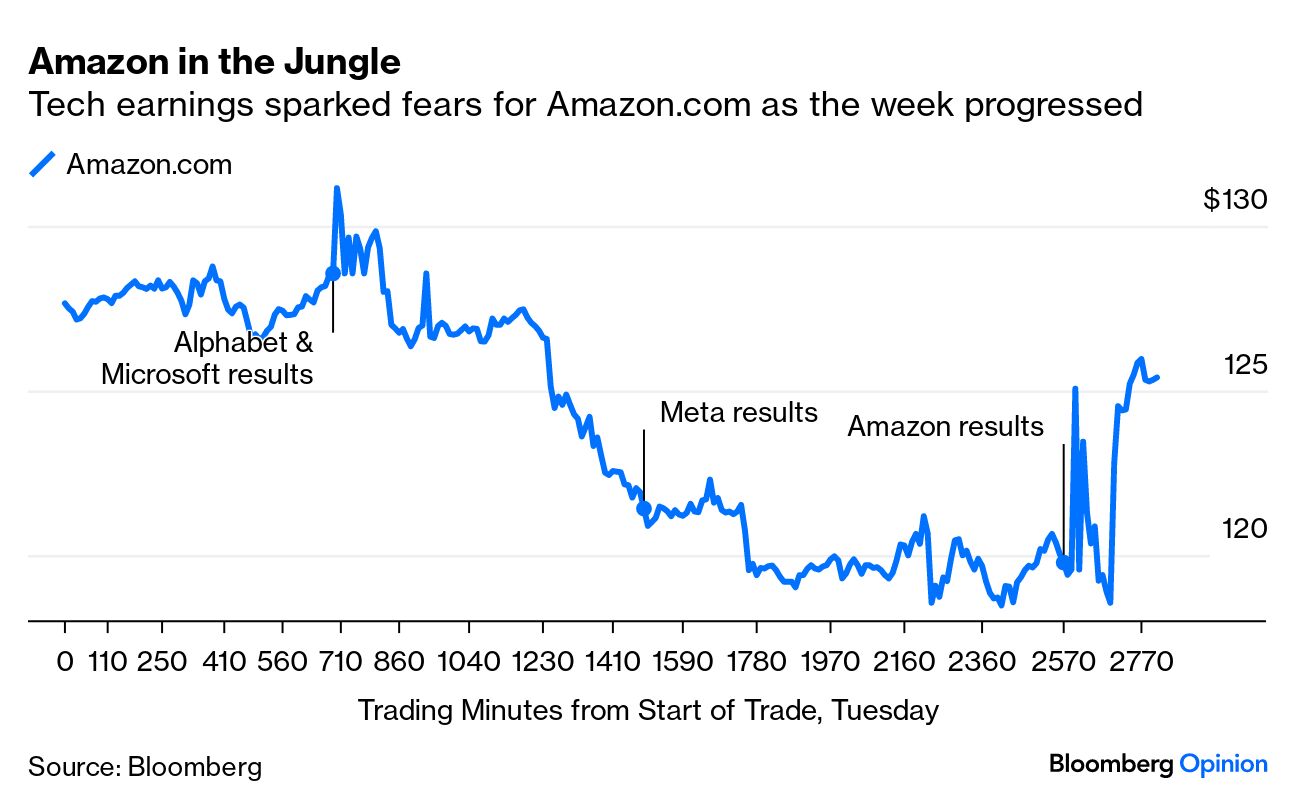

| All it took was a cold blast of reality from earnings season to thwart the relentless optimism that has been powering the Magnificent Seven, the biggest stocks in the S&P 500 by market capitalization. While their earnings were not too disappointing, the hopes hinging on the prospective growth of the big internet platform companies look to have left these firms vulnerable to the slightest disappointment. Take Alphabet Inc., which saw its shares plummet almost 10% — the most since March 2020 — the day after the Google parent reported a smaller-than-expected profit in cloud computing. The report was healthy, broadly speaking. Meanwhile, Amazon.com Inc.'s stock tumbled for two days after those earnings as traders speculated that it would have similar problems in Amazon Web Services. The company's results, after the close Thursday, looked to be ahead of expectations on both revenue and profits, but after-hours trading showed that investors still weren't sure. After its conference call, the company's stock has still not made up all the ground lost after the first tech results two days earlier:  Across the board, shares have slumped since reporting. Mimicking Alphabet's selloff is Tesla Inc., which posted a 9.3% decline after its third-quarter results fell below consensus estimates for profit, sales and margins. It's now trading below its 200-day moving average, as is Apple Inc. — which doesn't report until next week. For Facebook parent Meta Platforms Inc., its stock slid the most in almost 11 months after comments warning of softer advertising spending. Microsoft Corp. was least hurt after reporting strong sales, bolstered by recovering cloud-computing growth — but even that stock joined in Thursday's selloff, and has now shed market cap since its earnings were published. The following chart by colleague Subrat Patnaik illustrates the carnage the handful of stocks have seen, with about $386 billion off their market value vanishing. So large is the loss that the decline has brought the S&P 500 down 9.84% from its recent peak, almost reaching the popular definition of a correction. By the beginning this year, much of the froth had been knocked off the top of a tech rally that started during the worst days of the pandemic, only for the sector to roar back with a vengeance thanks to the excitement over artificial intelligence. Critics always knew this couldn't last forever. The optimism, as seen in the graph below, is waning as higher interest rates finally take effect. And many have come to depend on the "Magnificent Seven" stocks, which are still sitting on gains of more than 50% in 12 months, while the average stock has actually declined slightly. Louis Navellier of Navellier Associates, a veteran growth investor, was forthright about the problem. He pointed out that Meta had beaten estimates for both its top and bottom lines, but had cautioned on advertising spending for the future. That was all it took: This led to the stock going down 5.5%, but it's still up 126% year-to-date. After the pullback in Tesla and Google, both of which continue to trade down, the weight of the Magnificent Seven underperforming is really dragging down the major indexes, which are starting to break important technical levels. Only a third of the S&P companies have reported, and while the beats are strongly outpacing the misses, the guidance for 4Q23 has been less than hoped and is bringing down P/Es.

A big component of the problem is the steady deflation of the hype around artificial intelligence. According to a trusty measure produced by one of the Magnificent Seven, Google Trends, search interest in artificial intelligence spiked after the launch of ChatGPT last November. Before that, AI had been generating no more search interest than it had in 2004. That level of interest, always unsustainable, has dropped significantly: But it's not just earnings. Tech stocks entered this year with the odds stacked against them thanks to the aggressive Federal Reserve. Long-term Treasury yields provide the rate for discounting companies' future cash flows, so a higher discount rate will lead to lower valuations. This should be particularly true for stocks expected to deliver a lot of growth long into the future. It was remarkable that the Magnificent Seven had progressed so far with such headwinds. Their success in doing so in part reflected the belief that even at lofty valuations, they offered a better alternative to the 5% on offer from bonds than most stocks did. Peter van Dooijeweert, head of defensive and tactical alpha at Man Group, explained that this boosted the Magnificent Seven, but also left them open to a severe impact from any disappointment: If you're going to have a consistent equity earnings yield and a severe discount to what Treasuries are yielding, then equities are going to have to deliver something — and that delivery has to be growth. That's the story for me this year. The equal-weighted S&P 500 earnings yield hasn't delivered the type of growth to make me excited about owning equities versus bond yields at 5%. Whereas the Magnificent Seven, the narrative, if not the actual earnings delivery, seems to be they'll deliver this explosive growth. So you'll out-earn what you might earn in bonds.

As the following scatter chart from AllianceBernstein shows, it's not clear that the 493 non-Magnificent stocks in the S&P 500 trade at a multiple that fully takes into account the way bond yields have risen — but the valuation of the Magnificent Seven suggests extreme confidence that their growth can overcome any challenge; they are trading at quite an extraordinary multiple of their projected future earnings: This implies that there is a lot of room below if confidence is shaken; so this week's jolts shouldn't be that surprising. But this has ramifications for the other 493. To quote Quant Insight of London: Equity bulls need the "generals" to hold in. The Magnificent Seven are responsible for 2023's performance. Given poor breadth, if they roll over now there's a very real risk of a deeper correction. Aside from the idea of AI as a genuine game changer, the obvious argument for the Magnificent Seven to retain a bid is their role as a comparative safe haven. Typically, they have strong balance sheets and wide moats, in Buffett-speak.

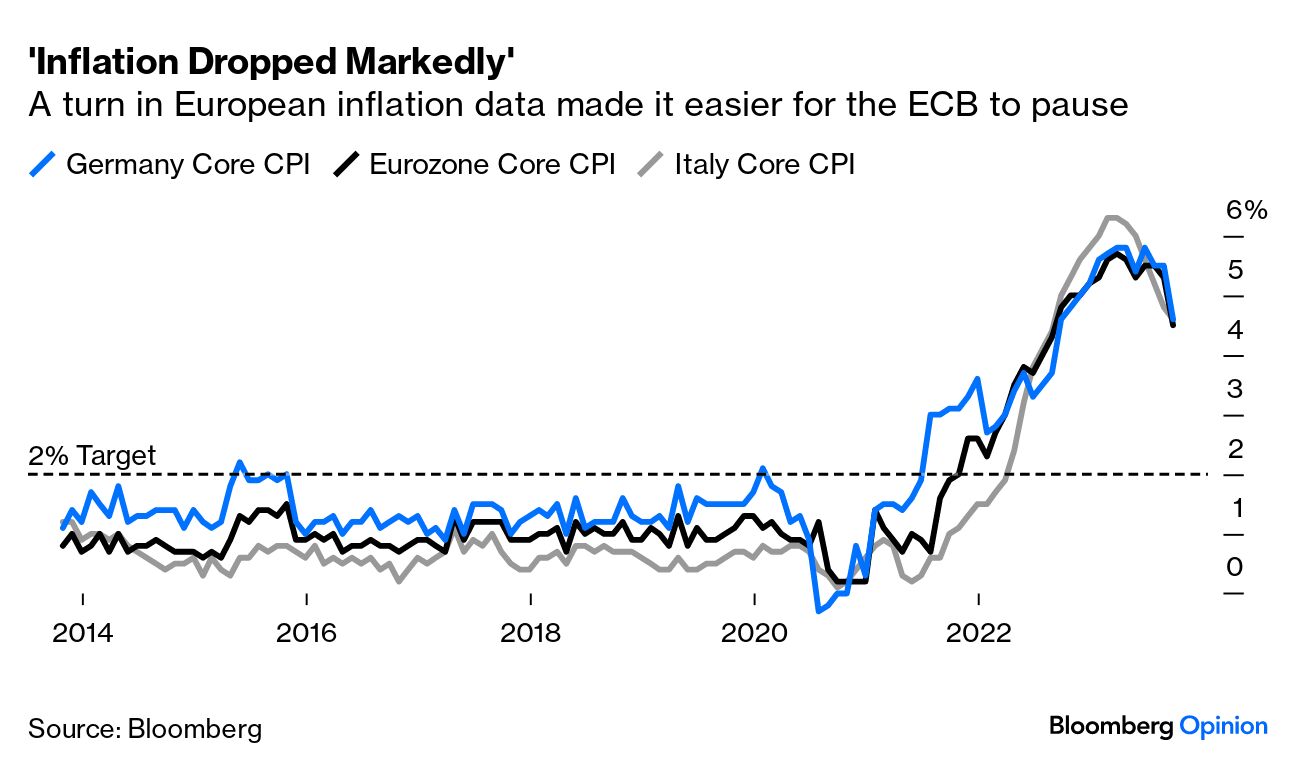

Just perhaps not quite wide enough. The overall Nasdaq-100 is now down around 11% from its July high. That means that it's erased about a third of its gains for the year, capped by the last two bruising days that wiped out $800 billion off share values. The tech-heavy gauge sank nearly 2% Thursday and 2.5% on Wednesday — its worst day this year. Even with this downturn, colleagues point out that even the broader Nasdaq-100 is "a long way from cheap," with a P/E multiple of just below 22. — Isabelle Lee It would have been safe to sleep through the European Central Bank's monetary policy meeting on Thursday. Christine Lagarde and her colleagues have sprung a number of surprises in the last three years, but they seemed determined not to hike rates this time around, and the health of the European economy (or lack of it) gives them precious little reason to do otherwise. Their long hiking campaign is at last on pause, and there's every reason to assume that it's over. If we look at how expectations for the ECB's target rate have moved since the end of June, the picture is of relative calm. Rates have risen by 50 basis points since then, as largely expected, and confidence is growing that they will stay stable for the next few months, before shedding those 50 bps by the end of the summer of 2024: Significantly, the ECB is now expected to start loosening policy earlier than the Fed, despite suffering from what appeared to be a worse inflation problem, and also having the disadvantage (from an inflation-fighting perspective) of a weak currency. There is now perceived to be almost no chance of a further hike in the eurozone (while that still seems possible, although unlikely, in the US), and the overnight index swaps market suggests a chance that the cuts could begin as soon as next March: The ECB could do this because inflation has turned significantly in the last few months, in a way that's almost uniform across the disparate economies that use the euro. As Lagarde put it, it's fallen "markedly." It's still too far above the 2% target to permit imminent cuts, so the hopes of an early easing might be overdone. But the case looks strong that no more tightening is needed:  The ECB has had help in ratcheting up financial conditions that wasn't available to the Fed. Banks still occupy a much more important position in providing credit in the eurozone than in the US. Thus, the sharp rise in banks clamping down on their standards for enterprise loans that was registered by the ECB's survey of lending officers earlier this week helps to curtail economic activity in a way that the March crisis for US regional banks evidently has not. (Just look at this week's data on US gross domestic product growth for the third quarter; they may be backward-looking, but they're still very telling.) Meanwhile in Europe, banking standards are still tightening, while demand for loans is dropping as badly as it ever did during the Global Financial Crisis, or the eurozone sovereign debt crisis that followed it: Unlike the Fed, the ECB seems to have an economy growing slowly enough to allow it to stop raising rates. Whether that's good news for Europe is another matter. Surely something has to budge soon in Japan? Earlier this month, the yen dropped below the level of 150 per US dollar, to be greeted immediately by what was obviously a significant intervention that sent the yen back to the 149 level. However, subsequent days showed the the Japanese authorities were concerned more with drawing a line in the sand at 150, rather than strengthening the yen further. After a few weeks that saw currency traders dicing with whether to take it through 150 again, the landmark arrived earlier this week. This time, there was no response:  To put that in broader context, this is Deutsche Bank's trade-weighted index of the yen, against the currencies of a range of its trading partners, going back to the beginning of this century. The yen is plumbing new depths. And while earlier bouts of extreme yen weakness were associated with deliberate attempts by the Japanese authorities to weaken their currency — in 2001, and again in the "Abenomics" era that started with the return of Shinzo Abe to the premiership in 2012, and again with the adoption of yield-curve control by the Bank of Japan in 2016 — this fall is happening without overt help from the government:  Even stranger, this is happening as the yield-curve control policy, relaxed three times over the last three years, appears close to the moment of abandonment. At the Bank of Japan's July meeting, the decision was made to create an upper limit of 1% for the 10-year Japanese government bond yield, doubling it from 0.5%. The BOJ made clear it didn't want to see 1.0% yields straight away, but developments since then make it fairly clear that it's happy to engineer a steady rise to that level: After years of wishing for inflation, Japan at last has it, and a weak yen is likely to encourage even more — along with more capital flight by Japanese investors parking money overseas. Higher yields would help. Does that mean that a further relaxation of yield-curve control could come as soon as next week? The BOJ has a longstanding penchant for taking the market by surprise, so it can't be ruled out. "Until now, we had expected the BOJ to raise its level of 10-year JGB fixed-rate purchase operations from 1% to 1.5% in January 2024," said Jin Kenzaki of Societe Generale SA. But the rise in US yields, along with American fiscal concerns, might change that. From the perspective of maintaining confidence, he said, "the BOJ may want to avoid being forced to re-tweak its YCC just three months after its last tweak." Even so, he says there is now "a 50-50 chance that the BOJ will raise its level of 10yr JGB fixed-rate purchase operations from 1% to 1.5% next week." That sounds about right. More thrills and spills to look forward to. My beloved Brighton & Hove Albion have just won their first ever game in the Europa League, and they've done it against the mighty Ajax of Amsterdam, four times champions of Europe, who gave us Johan Cruyff, Dennis Bergkamp, and Total Football. So that's pretty cool. It's a little sad that this is in part because Ajax are having what looks to be the worst season in their history. That is genuinely sad, because Ajax are impossible to dislike. Revising this clip, I see that Total Football looks more like hunting in packs and an extreme offside trap, but it certainly worked. And when Ajax football was at its best, as in Bergkamp's great goal against Argentina in the 1998 World Cup, it also prompted what is quite without question the best commentator's call of all time. Even if you speak no Dutch you'll know exactly what he's saying. Let's hope Ajax are back soon (but not until after they've played the return leg against Brighton next month). Have a good weekend everyone.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment