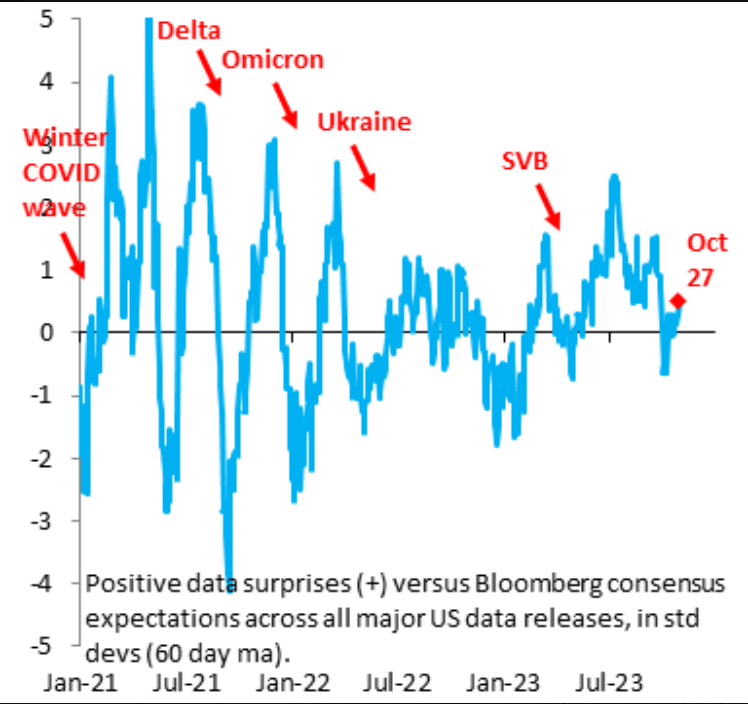

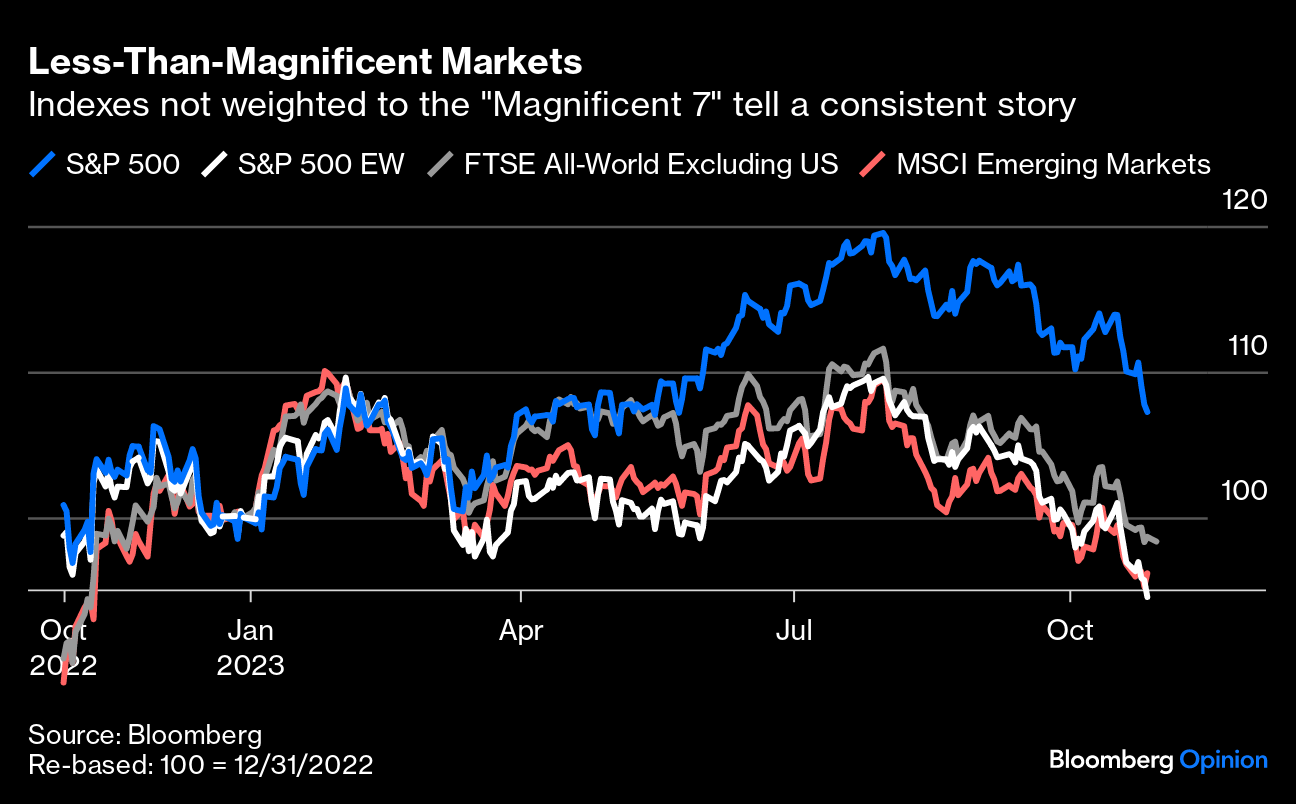

| The economy and the stock market are not the same thing, at all. In the short run, there's no particular reason to expect them to move in the same direction, even though in the long run they both tend to grow, with occasional interruptions. At present, the disjunction seems extreme: Last month saw both a blowout number for third-quarter gross domestic product growth, of 4.9%, and a selloff in the stock market that brought the S&P 500 more than 10% below its recent peak — satisfying a popular definition of a "correction." However, at present the two are more tightly linked than usual. The big question for stocks is whether the bear market is really over (with US prices still well above their lows from last year). If it is, you should take the opportunity to buy, and if the bear market merely hibernated and never ended, then you should take the chance to sell. And the answer to that lies in a question about the economy: Is there going to be a recession in the US? This is where it gets interesting. Bond yields have surged upward, and stocks have sold off, in large part because the assumption that the regional bank collapses earlier this year would drive a recession has proved incorrect. They might well yet contribute to an economic downturn, but the strength of the latest GDP numbers show that something more will be needed. According to Robin Brooks of the Institute of International Finance, the best explanation for rising yields is "that the US did NOT go into recession after SVB blew up. That's meant that — relative to bearish consensus — data kept surprising positively, which forced the yield curve to uninvert." He illustrated this with Bloomberg data in this chart:  Markets have capitulated on their belief in an imminent recession under the weight of a welter of positive data. That's been bad news for bonds, evidently. The implications for stocks are more nuanced, but in general there are precious few examples from history of a bull market starting other than when there is already a recession. That implies we should expect the bear market to continue if a recession is really ahead. The problem, as we've documented in Points of Return, is to squint and work out what's happening if you exclude the influence of the "Magnificent Seven" stocks — Apple Inc. , Amazon.com Inc., Alphabet Inc., Meta Platforms Inc., Microsoft Corp., Nvidia Corp. and Tesla Inc. — which dominate large-cap indexes. The S&P 500 is still up for the year, and only just 10% off its peak — but if we simply take an equal-weighted version of the S&P, in which each company accounts for only 0.2%, then we find it's down for the year, and slightly lagging the popular benchmarks for the world outside the US, and for emerging markets. The Magnificent Seven seem to be inhabiting a different economy:  Nicholas Colas of DataTrek Research points out that Friday's closing level of the S&P 500, of 3,839.5, is drastically at variance with the current estimates from Wall Street analysts, many of whom moved up their year-end targets for the benchmark during the summer when the market was rallying. He explains as follows: One simple metric we've used over the years to know when fundamentals have diverged materially from market sentiment is the difference between analysts' aggregate S&P 500 price targets and current prices. When the Street thinks the S&P should be 20% or higher than where it is actually trading, something has gone wrong. According to FactSet, analysts' current price targets on the index bubble up to 5,082. We are 23 percent away from that number today. Either the Street's estimates and price targets are way too high, or markets are excessively bearish. We've seen things break either way (stocks higher or lower three months later) whenever this happens.

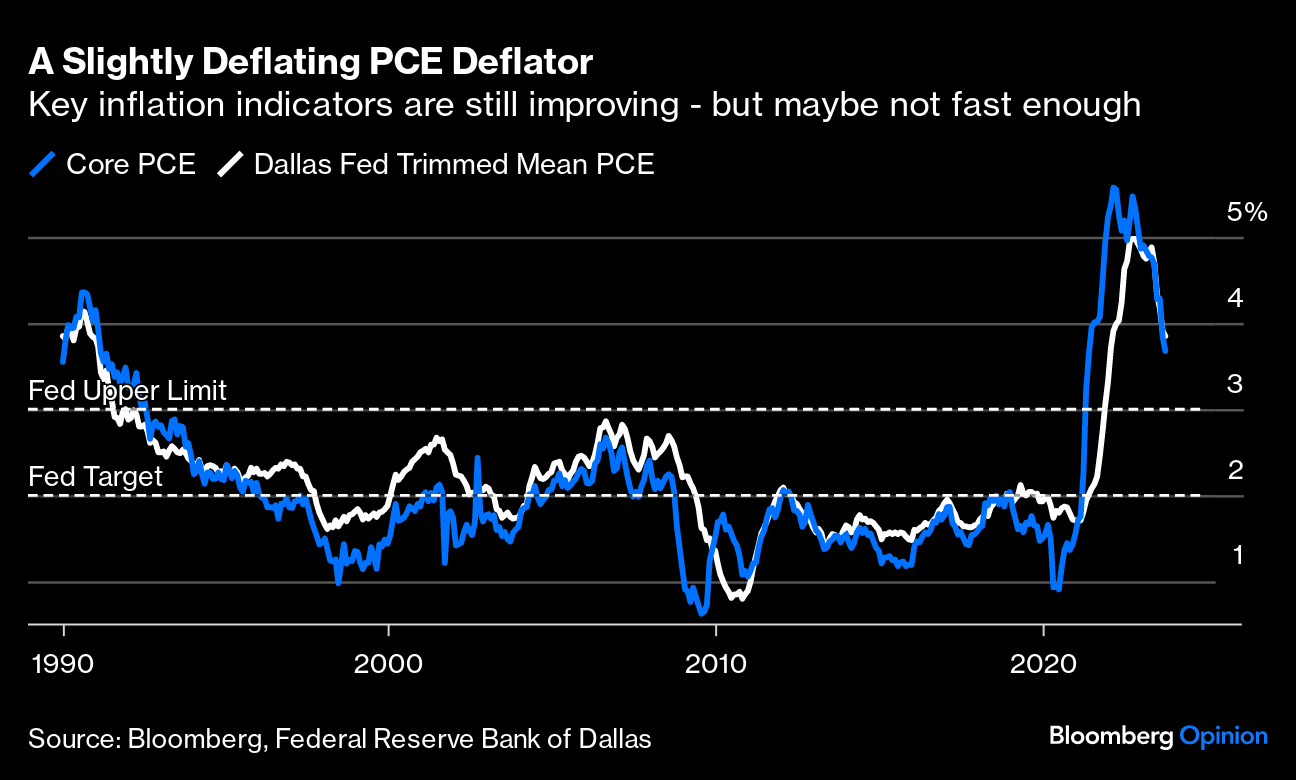

For indications that the market is indeed bearish, and possibly excessively so, the highly economically sensitive transport stocks are in a tailspin: On the face of it, after performance like this, we should brace for a trading bounce or a recession — or both. We hear from Jerome Powell and the Federal Open Market Committee this week. Barring a major surprise, there will be no rise in interest rates, meaning that the central bank will have been on "pause" since July. It's hard to imagine that Powell will renounce the option of hiking again, however, because inflation is not under sufficient control for him to do so. Last week saw the release of Personal Consumption Expenditure deflator data for September, the Fed's favored measure of inflation. If we look at two popular measures of underlying or core inflation — a straightforward "core" that excludes food and fuel, and a "trimmed mean" produced by the Dallas Fed that excludes the outliers and averages the rest — we find that both are decreasing, but remain above the Fed's comfort zone. Fed governors tend to be judged by their record in containing inflation, and that will make them hugely reluctant to claim victory just yet:  Looking into the entrails of the PCE data, Omair Sharif of Inflation Insights LLC also demonstrates that the distribution of products and services that are still seeing the highest inflation is likely to make consumers unhappy. The chart gives the proportion of PCE components showing an increase (in blue, and more-or-less back to normal), and the proportion of the expenditures that consumers are currently making where prices are rising, which is right at the top of the historical range: Thus, consumer attitudes might not improve as much as might otherwise be expected. That would generally imply a greater risk ahead of a loss of consumer confidence, which could induce a recession — although that certainly hasn't happened yet. These inflation numbers effectively make it impossible for Powell to do anything to try to talk yields down, even though higher interest rates mean a rising risk of a big credit event. Until that credit event actually happens, he has to continue on his current course. Komal Sri-Kumar, writing in his Srikonomics newsletter, explains the dilemma for Powell as follows: There is little expectation that the volatility in bonds will cause him to suggest an explicit reversal of policy — an end to Quantitative Tightening and a move toward lower interest rates. A policy reversal would cause a rally in risk assets and, in the process, making it even more difficult to bring inflation down to 2%. On the other hand, the recent turbulence in bonds must have sufficiently frightened the Fed into not providing a tough message. I do not expect benevolent Uncle Jay to say "Uncle" on Wednesday. He needs a credit event to push him to that stance.

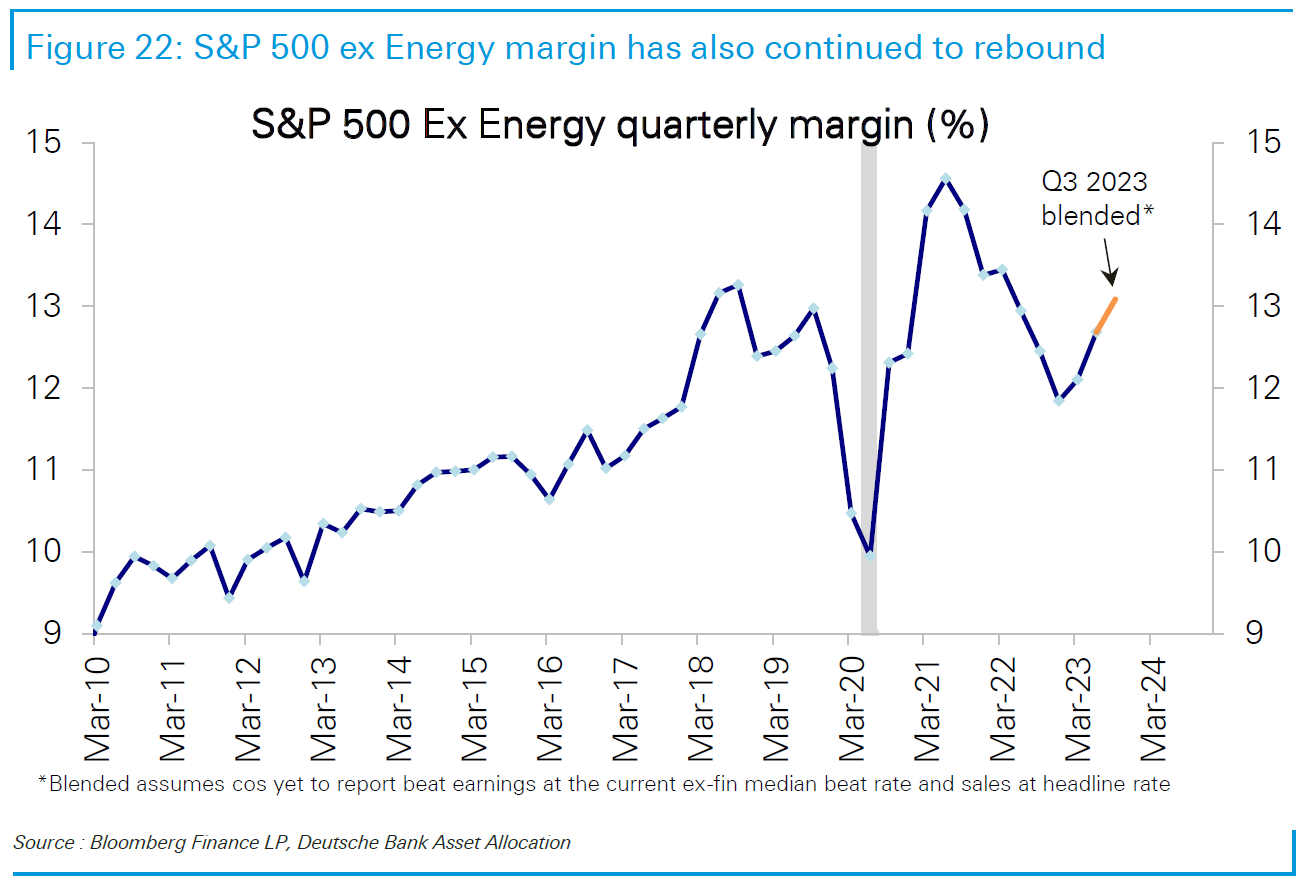

So limited is Powell's ability to change direction at this point that there's every chance his thunder will be stolen Wednesday by the Treasury Department's announcement of its borrowing needs for the quarter. The potential for that number to move the bond market looks very much greater than anything the Fed is likely to say. After all, as this IIF chart demonstrates, the market has been asked to swallow a lot of debt, and if the Fed keeps its word about stepping back, someone is going to have to buy more: The scale of the deficit and lending needs ensures that markets grow ever more geared to short-term moves in the economy. A recession would mean lower tax receipts and higher welfare payments; in current circumstances, Uncle Sam would probably have to pay up to finance that. Yet again, corporate earnings are subject to a magnificent distortion. All the Magnificent Seven except Apple and Nvidia have reported so far, and none has seen a rise in share prices on the back of it. Sarah McCarthy of Alliance Bernstein points out how lopsided the market has become: "The seven mega caps are expected to grow earnings in the third quarter collectively by +33% year-over year on 11% higher revenues versus the rest of the S&P, which is expected to have a decline of -8.6% in earnings with no growth in revenues." The Magnificent Seven matter immensely at present, then. But that can obscure the fact that at the aggregate level, more companies are surprising compared to their estimates than usual, and that earnings per share are on course to hit an all-time high. This chart from Bankim Chadha of Deutsche Bank AG blends actual results to have been reported so far with forecasts for companies yet to come: This is in line with what might be expected when the economy is performing better than many had feared. However, Chadha also points out that sales growth continues to decline, even if the very volatile energy sector is excluded, and has has generally disappointed predictions. It's nothing much to worry about as sales are growing well ahead of historical norms, but does demonstrate that Corporate America isn't feeling the full effects of a resurgent economy: Meanwhile, margins are now back to their pre-pandemic peak. On the face of it, this isn't great news for those worried about inflation, and will feed various negative narratives. It's impressive that margin growth has been achieved without big job losses to cut wage bills, but suggests that companies aren't spending that much on things that might help to boost the economy further:  None of this is consistent with a sudden shift toward recession, and thus should support the notion that we are in an interruption to a bull market. But there are more disquieting trends afoot, particularly in the guidance that executives are giving on earnings calls. They are being noticeably downbeat. Chris Watling of Longview Economics in London points out that several of the companies that reported earnings last week chose to highlight "a change in the macro environment in the fourth quarter (i.e. post the cutoff of their earnings report)." Meta was probably the highest-profile example, as it warned about weakness in ad spending (which Watling describes as a classic cyclical indicator that, again, implies companies are cutting back on spending they would otherwise like to make). The huge UK-based advertising group WPP made similar comments. Watling also drew attention to a negative assessment by the chief executive of Hershey, the big US confectioner: Many are cutting back on discretionary purchases, looking for deals, shopping at discount channels, and buying smaller sizes. We have also seen more category and brand switching.

Perhaps most significantly, the shares of TransUnion – a credit reporting agency that is heavily leveraged to the flow of consumer – fell by about a third last week after it reported disappointing earnings and withdrew its guidance for 2025. Most damagingly, Watling pointed to the CEO's comment that: "Cracks have occurred across consumer lending, especially in the lower credit tiers." The market's response, which may have been overdone, eliminated all TransUnion's outperformance of the S&P 500 since its 2015 IPO: Ultimately, this view from Watling strikes me as very reasonable. The surprising strength of the economy explains the dreadful performance by the bond market — but the evidence is falling into place that that strength won't last much longer: While the macro data is yet to confirm the recession (and indeed was notably strong in the third quarter), other evidence (anecdotal, corporate and yield curve, amongst others) is building.

This is where I try to lighten the mood. Given the news coming out of Gaza, that's difficult. There's nothing uplifting to be said about it. I tried to work up something about the victory of a very multiracial South African team in the Rugby World Cup as a sign that even the most intractable conflicts and injustices can be overcome, but that seems a bit trite. So let's talk about Matthew Perry, who died this weekend at 54. Apparently his long history of addictions finally beat him.  A master of one-liners and physical comedy. Photographer: Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic Particularly after his memoir of addiction was published last year, it's hard to view him through any other lens. He might suffer the same fate as Amy Winehouse or Whitney Houston and be remembered primarily for his dependencies. That would be a tragedy, because like them he was touched with genius, and his gifts are under-appreciated. He's famous for his character Chandler in the long-running sitcom Friends, which ended almost 20 years ago. The insecure one, he has proved over the last two decades to be by far the most memorable character; many in Generation X identify with him. His greatest moments are run down here by WatchMojo; he was best known for his sarcasm, and great one-liners that are now memes such as "Stop naming dwarves" or "can open, worms everywhere." But Chandler's enduring appeal isn't just about the great lines he delivered, quite a number of which Perry had written himself; he was also a brilliant physical comedian. For examples of this (for which I thank my sister Lizzie Conrad Hughes, who is currently completing a doctorate on performing Shakespeare, and has long avidly explained to me just how good Perry was at comedy), try the One With Two Parties or his honesty about massages, or perhaps the scene where he breaks Monica. For physical gags that would have worked perfectly in silent films, watch him in the act of smoking (painful though it can be given all we now know about Perry's addictive personality), or the outtakes from the "pivot" scene (which has come in useful of late for describing the Fed). For perfectly timed comedy where you couldn't see his body at all, try the one where he spends Thanksgiving in a wooden box. He was a special talent, and it's a tragedy he's gone. But these scenes should help us get the week off to something like a cheerful start. Let's thank him for that.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment