| It wasn't quite like 12 Angry Men; to be more accurate, the latest meeting of the nine-member Bank of Japan Policy Board must have been more Eight Angry Men and One Woman. But such was the anticipation that had been allowed to build up that even their decision to do effectively nothing still turned out to be a big event. Early Monday (or very late Monday in Tokyo), the Japanese news service Nikkei published a story saying that the central bank would consider changing its policy of yield-curve control (YCC) that has effectively set a limit of 1% on the 10-year Japanese government bond yield. The last time Nikkei came out with a story this confident a matter of hours before a bank meeting, in late July, it was indeed followed by the news that the yield allowed under YCC was being doubled to 1.0% from 0.5%. That contributed to a rout in Treasury bonds that took shape the following week. BOJ perhaps inadvertently egged on the drama. Alone among the major central banks, it doesn't commit to a precise time to announce policy. As the minutes dragged by, and an announcement was still not forthcoming, that increased the impression that the board members must be having an impassioned argument, and with it the perceived chance that they would end by doing something. Also, as the BOJ has long reserved the right to take the market by surprise in a way most other central bankers no longer feel comfortable doing, as described here by Bloomberg Opinion colleagues Daniel Moss and Gearoid Reidy, it seemed all the more credible that they would move. But they didn't. You can tell easily enough from this graph of the yen exchange rate with the dollar during Monday (all times are New York hours) where the Nikkei leak story came, and when the actual announcement occurred (21 minutes later than average): The ramifications for now are that one of the greater global forces keeping Treasury yields down remains intact. That might well encourage more buyers of US bonds. Meanwhile, as we now know that the central bank isn't going to help in propping up the yen, the spotlight turns to Japan's Finance Ministry. The yen briefly dipped beyond Y150 per dollar after the announcement, a level at which there has been intervention in the past. Is there the will to keep the yen from getting too weak? There is also, as I write at midnight Eastern Daylight Time, considerably more event risk from Governor Kazuo Ueda's press conference. Presentation materials released by the central bank suggest that it's trying to present its decision as an easing of YCC, as 1% will now be a "reference" and it will react "nimbly" either just below or possibly just above the 1% level. Evidently few are convinced at this precise moment, but that appears to be the message from these visuals, provided by Reidy: In particular, Ueda might have to explain this passage from the BOJ statement that Reidy argues suggests that BOJ is no longer actually committed to controlling bond yields, but is prepared to let the market decide (much as the Fed in the US appears to be): It is appropriate for the Bank to increase the flexibility in the conduct of yield-curve control, so that long-term interest rates will be formed smoothly in financial markets in response to future developments.

There'll be time enough to write about that tomorrow, as an action-packed macro week continues. For the BOJ, though, there's also a warning. Trailing stories in advance with friendly media outlets can sometimes be a part of a central bank's messaging, but it can be dangerous. And it's a really bad idea to let stories get out and not follow through. Without the leak, and without the long time the governors spent in their meeting, this would have been a non-event. As it is, it's created some drama. That's not a good idea at the best of times, and certainly not now. Wednesday Nov. 1 is an FOMC Day. We will hear from the Federal Open Market Committee in afternoon proceedings that traditionally dominate the day. But possibly not this time — and it's not just because of the download of first-day-of-the-month data. At 8:30 a.m., the team at Treasury under Janet Yellen will announce its borrowing plans for the next quarter. And at this juncture, what Janet Yellen says probably matters more than anything Jerome Powell can say later. Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank AG suggests that the last such refunding announcement, on Aug. 2, has "arguably proved to be the most important macro event of the last three months." A look at the rise in 10-year yields since then, which abruptly took off on the day of the Treasury announcement, after having stayed flat for 10 months despite repeated Fed hikes, suggests this might well be right:

As is well known, the Treasury is somewhat boxed in by a ballooning federal deficit, which makes funding much more of a challenge. The rise just since 2022 has been startling, driven by lost or delayed revenues and by increased expenditures. Colleagues Christopher Condon and Chris Anstey produced this summary last month:

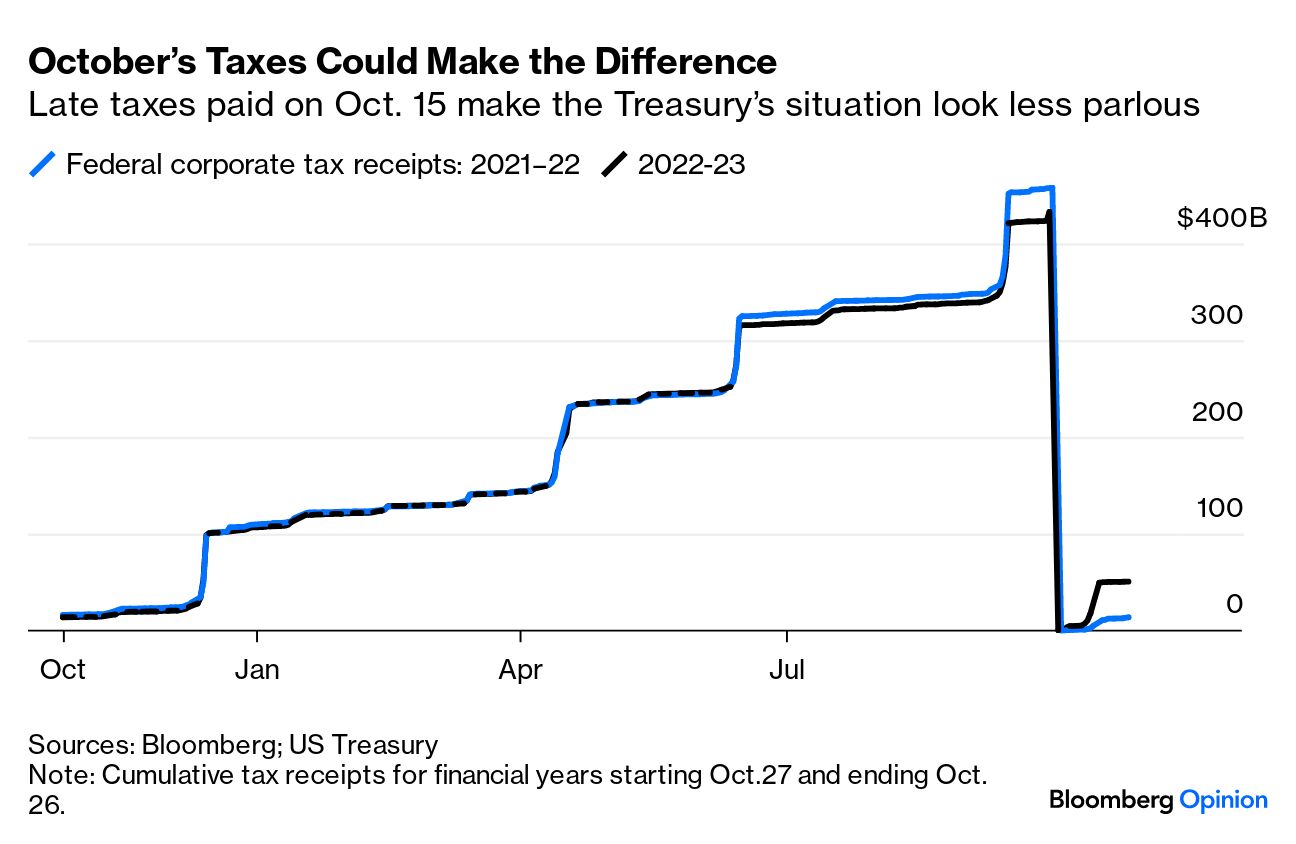

However, Monday did bring moderately positive news, from the point of view of those who don't want to see bond yields continue to surge. The Treasury announced that its planned borrowing for this quarter will be only $776 billion, which sounds like a lot but is still down $76 billion from the $852 billion estimate published in August. Late payment of taxes by Californians who were given an extension during the wildfires earlier this year helped boost the Treasury's coffers:  The news had an effect, but not a big one; the 10-year yield dropped to 4.85% from 4.88% immediately after the report, but ended the day at 4.89%. The big item that investors want to know is whether the Treasury will choose to will relieve some of the pressure on 10-year and other longer-dated Treasuries by shifting more issuance toward short-term bills. That's possible, but Steven Zeng of Deutsche Bank AG argues that the Treasury will probably not cut back on long-term bond issuance (known as "coupon increases" in the jargon) for the following reasons: (1) the Treasury gave guidance of further coupon increases in August, and it is unlikely to violate its principle of being "regular and predictable" for short-term changes in the market environment;

(2) the bills' percentage of total debt is elevated and still rising;

(3) the recent term premium repricing reflects an overdue recovery rather than an overshoot to the upside, and the move may not be fully finished yet, so delaying increases into the future could be counterproductive.

If the Treasury does want to shift toward bills, there is probably room for them to do so. As this chart from Bank of America shows, the amount of bills left in the hands of primary dealers (meaning that they couldn't find institutional buyers for them) has risen, but not to the kind of scary extent that might have been feared:

Unlike the Bank of Japan, the Treasury doesn't like springing surprises on the market. For this we can be grateful. It's unlikely they will administer much of a shock. But after the last three months, it's likely to command even more attention than the FOMC. This is one of those rare occasions when there is more doubt over what Treasury will do than the Fed. Commercial real estate is a problem that hasn't gone away. The reasons for concern about office property are obvious to anyone; the growth of working from home reduces revenues while higher interest rates increase costs. Put them together and there's reason for acute concern. Those concerns abated somewhat after the Fed eased collateral requirements for banks in March, in a move that effectively provided new liquidity for the market. But that appears to be over. Commercial mortgage-backed securities are now trading at as wide a spread over equivalent Treasury bonds as they did during the regional banking crisis in March. With the exception of a few weeks, that spread — at nearly 150 basis points — is as high as it's been in a decade, barring only a few weeks during the Covid lockdowns: This spread did exceed 1,000 basis points for a while during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, but most would hope to avoid a repeat of that at all costs. It's also noticeable that spreads of relatively low-quality BBB-rated CMBS have ballooned — even as high-yield corporate bond spreads remain reasonably contained, as demonstrated in this chart from Capital Economics: As might be expected, the eye of the storm is in US offices, particularly New York City. Vornado Realty Trust, a heavily leveraged developer whose name appears on the ground floor of many Manhattan skyscrapers, went through a crisis of confidence earlier this year, and weathered it. But its share price is giving way again and is back below the 200-day moving average, so the trend continues to be downward: Meanwhile, Bloomberg's index of US office property real estate investment trusts (REITs) has dropped to a new post-pandemic low, again surrendering what had looked a promising recovery. As with the banking sector, it's noticeable that the US has now parted company with Europe. Until the big turn in the risk markets about 12 months ago, office REITs on either side of the Atlantic had tracked each other closely. The US is now lagging the eurozone significantly: This is in part because European REITs offer a more generous yield relative to German bunds than their US counterparts do relative to Treasuries. Indeed, the yield on the broad Bloomberg US REIT index has just dropped below that of the 10-year Treasury yield, while the equivalent NAREIT index shows Eurozone REITs offering a continuing yield pickup compared to bunds: For a further clue that the commercial property problem is intimately linked to the travails of the regional banks, this is how the S&P 500 has performed compared to both of them over the last two years, in a chart suggested by John Higgins of Capital Economics: Higgins suggests that the ultimate implications are firmly bearish: Structural changes in the demand for commercial property in the wake of the pandemic partly explain why it — and office property in particular — has come under so much pressure. But we wouldn't be surprised if next Monday's quarterly Senior Loan Officer Survey by the Fed revealed a further tightening by banks on ordinary business loans as well as on those for commercial property, and that demand for both types remained soft.

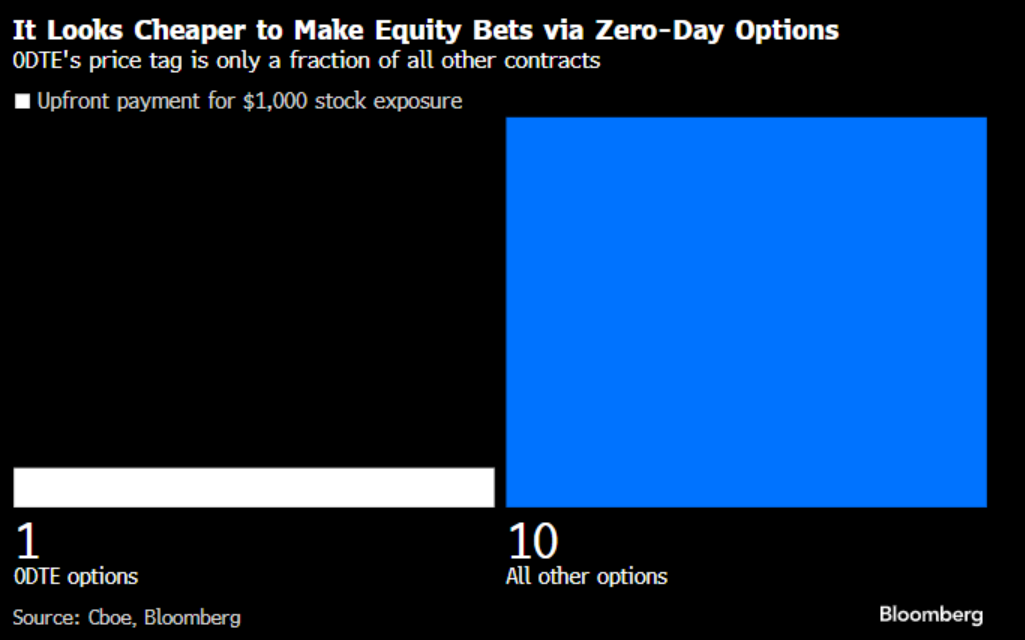

So, don't ignore those towering skyscrapers. And if all of this sounds dreary, there are much more optimistic vibes emanating from Florida… Hello, Isabelle here reporting from sunny Orlando where I attended (and moderated a panel at) the MoneyShow, a financial conference for individual investors — the affluent, active day traders and their financial advisers. The sun was shining throughout and I had a great view of greeneries. And the positive people in attendance found far more reasons to be optimistic amid this turbulent market than you generally hear amid the institutions of Wall Street. Of the more than 1,100 attendees, all seemed to have but one goal: to generate income. The main hall and all the breakout rooms buzzed with various ideas on how to derive an income from anything from real estate to commodities. Participants eagerly asked questions, often spilling over the scheduled time. They wanted to know how to position for a recession; whether small caps are a great buy at the moment; and whether gold can keep outperforming. And the market horizon looked almost as inviting as the view from the hotel:  Photographer: Isabelle Lee One theme did strike me based on the number of panels and speakers: the interest in options. Options trading has been around for decades, and the big options platforms have long been evangelizing their wares at conferences, but the force stirring the excitement at this year's show was a relatively new arrival: zero-day-to-expiration contracts, or 0DTE. They allow traders to bet on the daily gyrations of US equity benchmarks by dashing in and out of trading contracts that expire within 24 hours. There have been various estimates of how much retail investors comprise when it comes to 0DTE volumes. Cboe Global Markets in August put it to at least 30% — and possibly up to 40% — which is far higher than the roughly 5% estimate given by academics and researchers at firms like JPMorgan Chase & Co. Judging by the mass of enthusiastic 0DTE traders in Orlando, the Cboe estimate sounds very believable. Such trades give Wall Street pros and day traders alike the power to turn a $1 investment into a $1,000 stock bet. So it's not surprising, although admittedly rather unnerving, that it has become a popular tool for retail traders, many of them retired, who treat their portfolios as an all-consuming hobby. "Put another way, traders are getting $1,000 of stock exposure for every dollar they spend on 0DTE. They would need to spend 10 times that to get the same equity position using derivatives with a longer lifespan, a Bloomberg analysis on Cboe's data shows," colleague Lu Wang wrote.  Warren Buffett, something of a saint to many MoneyShow attendees, famously described derivatives as "weapons of mass financial destruction," so this is a tad disconcerting. But it isn't surprising. Mike Larson, vice president at MoneyShow, said there was huge retail interest in options and 0DTE, "and we just respond to demands from attendees." To be clear, they are warned that the bets don't only go one way. Justin Zacks, a former Bloomberg journalist who is now at online trading platform Moomoo Technologies Inc., told them clearly: "It's very risky." To Kim Githler, founder and CEO of the MoneyShow, what's important is education. "The individual investor is the most powerful they have ever been," she said. "They have become far more savvy than anytime in history." They don't have quite the weight in the market that they had 25 years ago, as baby boomers approaching retirement helped to pump up the dot-com bubble; but there are cheaper and better tools for them now, and they're using them. — Isabelle Lee Bob Geldof and the Boomtown Rats famously didn't like Mondays. US markets, it turns out, really, really like them. The following extraordinary chart was posted on X, formerly Twitter, by the Bespoke Investment Group: This is quite stunning and it's hard to believe it's a total coincidence (although it might be). Earlier this year, several rescues associated with the regional banking crisis were negotiated over the weekend and announced on a Monday morning, so that might have something to do with it. It's also the most common day for the announcement of mergers and acquisitions. But it's still quite something. The downer is that the biggest Happy Mondays this year, when the S&P 500 rose more than 1%, were all followed by slight falls the next days. But Tuesday's gone quickly. If anyone has any ideas why there's such a strong Monday effect, please tell. In case anyone didn't get the reference, 12 Angry Men is one of the greatest movies ever made. It keeps the unity of time, and is virtually all set in a claustrophobic jury room, as a team of jurors ever more angrily thrash out whether to send a young man to the electric chair. This was their final decision. Always worth watching.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment