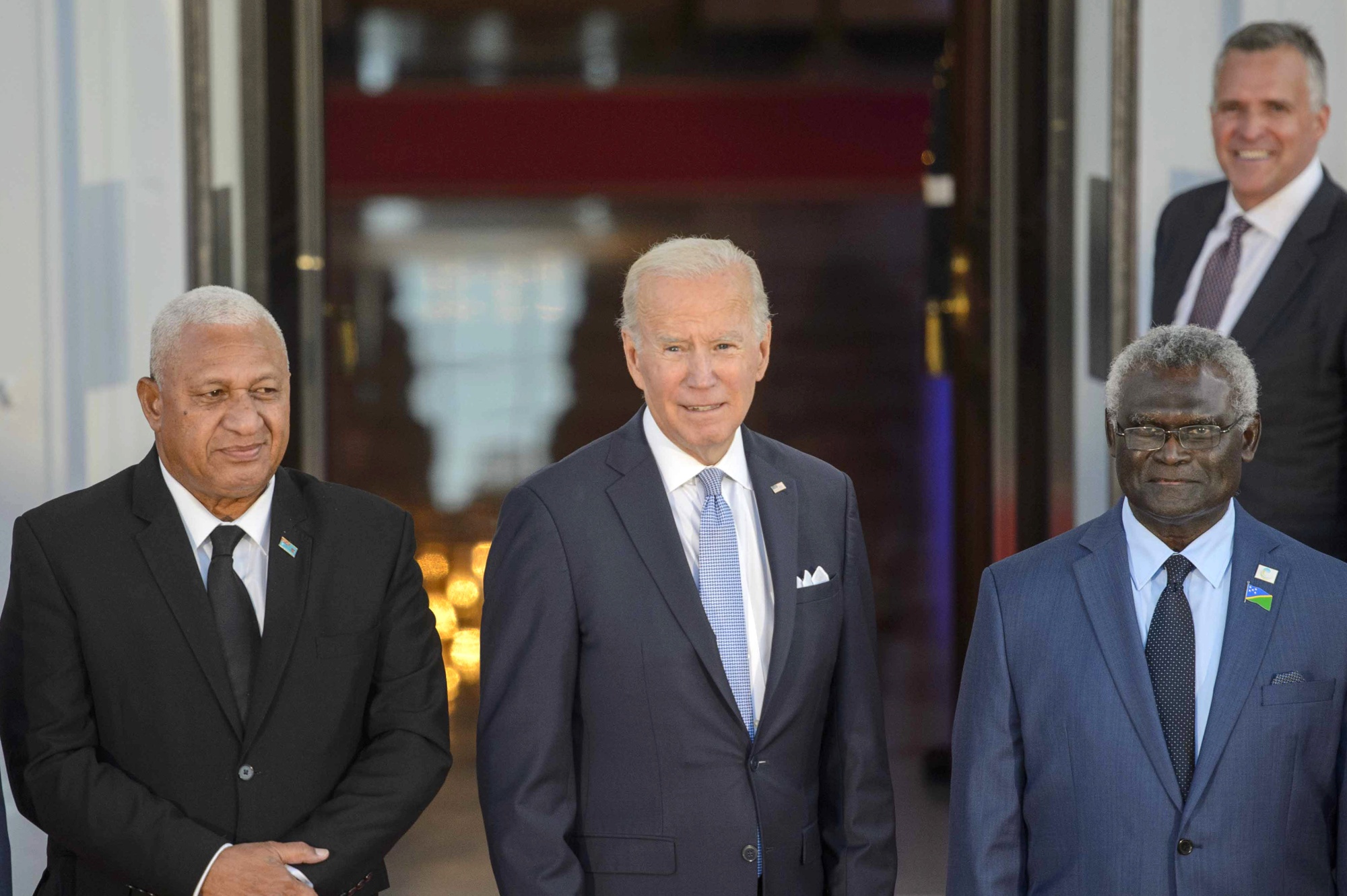

| Bloomberg's New Economy Forum returns to Singapore Nov. 8-10 as the world's most influential leaders gather to address critical issues facing the global economy. This year's theme, "Embracing Instability," focuses on underlying economic issues such as persistent inflation, geopolitical tensions, the rise of AI and the climate crisis. Request an invitation here. Perhaps the most frustrating thing in a football (soccer) match is an own goal. They also look pretty bad when they happen in other situations: say, for example, as part of Cold War 2.0. This week, the White House hosted a summit with Pacific Island nation leaders, part of Washington's catch-up strategy in a once-vital but long-forgotten region. There was a notable absence though: Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare of the Solomon Islands, an archipelago northeast of Australia where the US suffered thousands of casualties in World War II. Sogavare reportedly skipped the gathering because he wanted to avoid a "lecture." That was a win for China, which has sealed a security agreement with the Solomons and is building new port facilities and upgrading roads and other infrastructure—offering the country the things that matter most for its people's development. The curious thing however is that China isn't even paying for those projects, at least not entirely. Then who is? The $170 million initiative is being financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB)—to which Japan, Canada, western Europe and (you see it coming don't you?) the US are the main capital providers. So an institution set up by the West is financing a build-out of Chinese influence. Nothing but net.  US President Joe Biden, center, Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, right, and Fiji Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama, left, in 2022. Photographer: Bonnie Cash/UPI In other words, as much as the US, Australia and other Western powers may be concerned about China's increasing influence in the Pacific, they're not maximizing the messaging power behind the fact that they are the ones financing development that's already underway. It's another example of the West having to exercise muscles that atrophied in the decades after the Berlin Wall fell—a period of de-escalating security tensions and economic globalization that in hindsight looks to be the exception, not the rule. But evidence of a new workout regimen was evident at the recent White House summit: the US is mobilizing the Peace Corps—a Cold War-era soft-power creation of President John F. Kennedy—back to the Pacific. A challenge for Washington and Tokyo (which is the lead Asian shareholder of the ADB and picks its president) is that while they have the money, they don't really have the same capacity as China to build anything. China Civil Engineering Construction Corp., one of the biggest central government-owned enterprises, was the sole bidder for the Solomons project. Even so, the West arguably isn't capitalizing on (as the Center for Strategic and International Studies dubbed it) "a mechanism to achieve its economic and political interests and counterbalance China's influence" in the Asia-Pacific region.  A Philippine Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources ship, foreground, monitors a Chinese coast guard ship near the entrance of the Chinese-controlled Scarborough Shoal on Sept. 22. Photographer: Ted Aljibe/AFP China has its own "own goals," too. The same day Washington hosted Pacific island leaders, the Philippines took what the Pentagon described as a "bold step" in countering Chinese ships and their activities in the South China Sea. The Philippine Coast Guard removed a floating barrier that it said China had installed in a disputed shoal. China described its neighbor's actions as "nothing more than self amusement." It was the latest in a series of incidents in recent months that's showcased cooling ties between Manila and Beijing. What's striking about these tensions is that, several years ago, the Philippines was overtly aligning with China. "I announce my separation from the US," then-President Rodrigo Duterte said in 2016 after a meeting with President Xi Jinping in Beijing. Three years later, he said in a state of the nation address that China was "in possession" of the West Philippine Sea and his administration invited Chinese vessels to fish there. His hope was the realignment would unleash large-scale funding of Philippine infrastructure and even joint development of under-sea energy assets. Beijing didn't deliver. Most big-ticket projects announced with great fanfare didn't actually see construction. And the friendly posture adopted in disputed maritime areas was still, as of 2021, met by swarms of Chinese vessels pushing Beijing's claims. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., Duterte's successor, has pivoted powerfully back to the US, marking a major reversal for China. While the Solomons may be a useful stopover for Chinese vessels in the South Pacific, the Philippines represents a massive—decidedly non-floating—barrier. In this case, it was China that put its foot wrong. Why didn't Xi's administration give Manila the projects it wanted and ease off on the intimidation of Philippine vessels? A similar question could be asked of Beijing's handling of Italy, the one Group of Seven nation to sign up for Xi's signature Belt and Road initiative (BRI). When it did so in 2019, it offered China an investment bridgehead in the European Union's third-largest economy, a potentially stunning coup. Yet Chinese investment in EU members that didn't sign up for the BRI ended up far outstripping what went to Italy. Little wonder that Rome has now decided to pull out of the whole thing, with a nod in the direction of Washington. "China hasn't done a very good job of exploiting these opportunities that have come their way—and Italy and the Philippines are two good examples," said Bonnie Glaser, Asia program chief at the German Marshall Fund of the US. At the end of the day, the Chinese leadership "overestimated their ability to use a very small box of carrots," Glaser said. "They thought they would get a lot for it. And I think maybe they just don't understand the target countries that they're trying to woo." When it comes to own goals, the score seems to be 2-1 with America in the lead. By default, of course. —Chris Anstey Get the Bloomberg Evening Briefing: Sign up here to receive Bloomberg's flagship briefing in your mailbox daily—along with our Weekend Reading edition on Saturdays. |

No comments:

Post a Comment