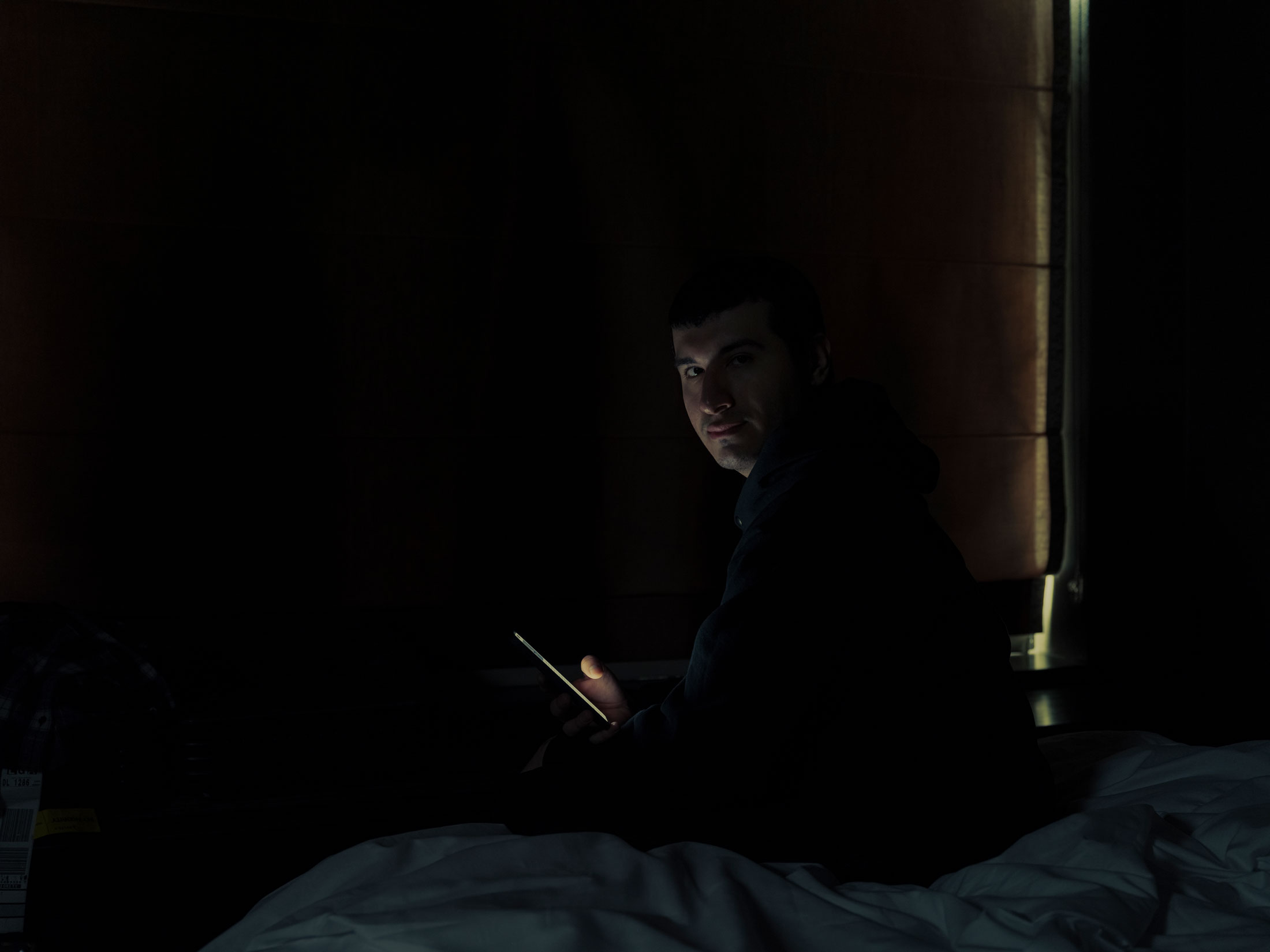

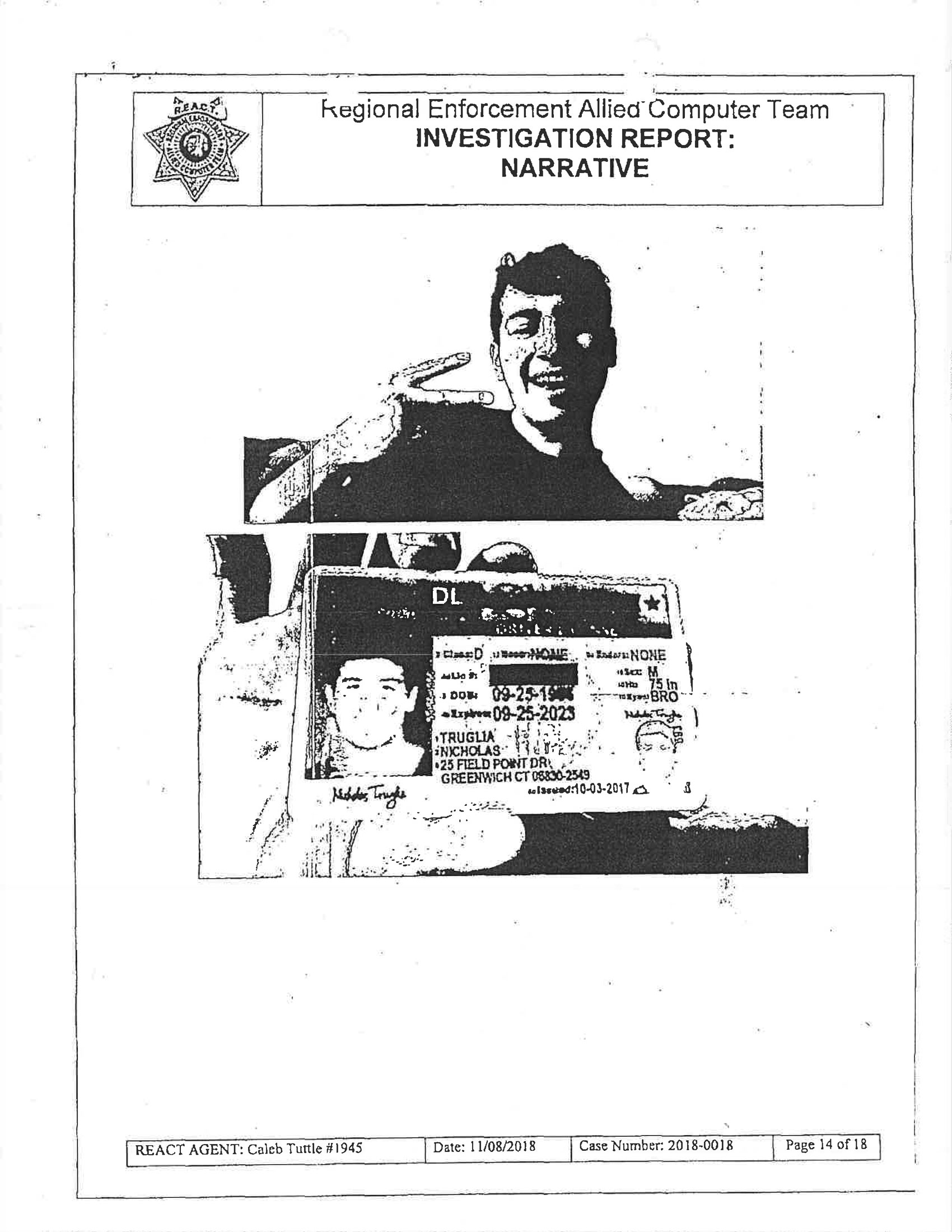

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter that brings an insightful magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek right to your inbox, in its entirety—and for free. We cover a lot of scams here, so the bar is pretty high to get our attention. This story, though, by Margi Murphy and Drake Bennett, certainly did. They explore a world of teen scammers, a "whale" and a fairly simple operation that netted millions of dollars. But the crime, really, is only the start of the story. You can also listen to this story or see a video about the hack. To get more from Businessweek, sign up here. In January 2018 the Consumer Electronics Show brought its lanyarded hordes to Las Vegas, as it does every year, and Michael Terpin was among them. Then 60, he was hosting a cryptocurrency event at Caesars Palace to coincide with the mammoth tech conference. He and his wife, Maxine, were at a home they own in Vegas, getting ready for opening night, when Terpin received an email from Google telling him a new device had gained access to one of his accounts. He yelled up the stairs to Maxine: "I think we're getting hacked again!" The previous summer, someone had hijacked the Terpins' mobile numbers, getting their phone service providers to transfer the numbers to phones the attackers controlled. The technique is known as "SIM swapping," after the Subscriber Identity Module, or SIM card, the small chip that gives a phone its unique identity on a cellular network. The SIM isn't swapped so much as the phone number, though. Transferring a number to a different phone with a different SIM card can give a hacker a way into someone's email, social media and online storage accounts. It can be as simple as clicking the "forgot my password" option on one of the many sites that give users the option of verifying their identities with a texted code. Whoever enters that code is presumed to be the account holder and can get in. In some cases, they don't even have to change the password. The first attack against the Terpins, in June 2017, hadn't been devastating. The hackers had failed to find what they were likely looking for: access to Terpin's cryptocurrency. Terpin is a prominent crypto investor and marketer, and he'd made no secret of his extensive holdings. But the thieves did manage to fool a few of Terpin's friends by sending them messages impersonating him and asking for Bitcoin they supposedly owed him. The friends collectively sent the thieves about $30,000 worth. Afterward, the Terpins were told by their carriers, T-Mobile US Inc. and AT&T Inc., that they would get a heightened level of security on their accounts. No SIM swaps to new devices could be made, they were promised, without a PIN. In Vegas seven months later, Terpin could see that the extra security had failed. When he received the alert from Google, he immediately looked at his iPhone. If the hackers had managed to port his number onto their phone, his own device would have been disconnected. To his temporary relief, it was still online and working. So was Maxine's. But then he remembered an older BlackBerry he rarely used. He dug it out and his stomach sank: No service.  Terpin and his wife, Maxine. Photographer: Erika P. Rodríguez for Bloomberg Businessweek While Terpin furiously checked his various crypto wallets, Maxine got on the phone. "There's a crime going on right now," she told a customer service rep with AT&T. She pleaded with them to disconnect the hijacked phone number but was transferred to the fraud department, then put on hold. It took an hour and a half before AT&T got the hackers' phone offline. In the meantime, Terpin had determined that his largest wallets and his accounts at the crypto exchanges were untouched. But he has a lot of wallets—"probably 50," he estimates. A longtime public-relations consultant who made his first fortune in the dot-com era, he'd since become a professional crypto promoter, offering his services to the creators of new coins and exchanges and taking payment in their tokens. Two days after the Vegas hack, he noticed that an obscure coin named Steem had gone up in price. Terpin had some, he remembered—about $60,000 worth. He checked the Steem wallet. The coins were gone. Terpin stayed up all night going through his wallets. A million dollars' worth of Skycoin was gone. So were his Triggers—a cryptocurrency he'd touted as a method for controlling internet-connected "smart" firearms through the blockchain. Like many of the crypto ventures he was involved with, the vision hadn't panned out, but his 3 million Triggers were still worth some $22.7 million. Or rather, they were until that week, when the thieves sold them all at once and crashed the market. Terpin was beside himself. Later that year, in August 2018, he sued AT&T for $224 million. In the complaint, he argued that the carrier, despite its assurances, had failed to protect his data. "What AT&T did was like a hotel giving a thief with a fake ID a room key and a key to the room safe to steal jewelry in the safe from the rightful owner," the suit alleged, "or, even worse, simply handing over the same keys to a known impostor when someone slipped them a $20 bill." This type of hack is proliferating: Last year the FBI received 2,056 SIM-swapping complaints, with losses totaling $71.6 million, up from 1,611 complaints and $68 million in losses the year before. Experts say the true figures are likely higher. SIM swapping doesn't require real technological chops, only a willingness to deceive or bribe telecom customer service reps. It preys on the industry's emphasis on convenience and cost over security. Terpin's quest for justice would come to consume his life, entangling him in a world of bling-crazy, clout-obsessed young scammers. Fortunately for him, some of their favorite targets would turn out to be each other. A month after Terpin sued AT&T, 20-year-old Nicholas Truglia was at home in his New York City apartment, trying to piece together the previous evening. He'd brought some friends back from a nightclub to his place in a luxury residential tower in Hell's Kitchen, and he'd had way too much to drink—that much was clear. He woke up with a cut lip and blood on his couch. His laptop was missing, he says, along with some hardware wallets—electronic devices that store cryptocurrency keys offline—and his actual wallet, with whatever fiat currency it contained. That weekend, after patrol officers and a detective had come and gone, one of his friends from the night before, Chris David, was right back in Truglia's apartment, sitting on the couch and playing Fortnite. He had brought back Truglia's laptop, which he'd later say Truglia had asked him to take for safekeeping. David did odd jobs in wealth-adjacent industries, working, among other things, as a private jet charter broker. Truglia wore a $100,000 Rolex, tweeted pics of himself on private planes and once informed David he wanted to buy a McLaren sports car. He told people he'd made tens of millions in crypto, though he seemed to spend most of his time working out or playing video games. He and David knew each other from the gym. Along with the other guys who'd been over when Truglia passed out, they liked to hit celebrity-courting Meatpacking District clubs such as 1 Oak and the Up&Down, blowing tens of thousands of dollars on premium tequila and prestige cuvée Champagne.  From court filings, David and Truglia in an AT&T store while allegedly trying a SIM swap. Source: Superior Court of California/County of Los Angeles On Truglia's sofa, as David blasted his way through Fortnite, they went over the clattering of David's digital firearms. Their posse wasn't exactly a band of brothers. They seemed to take gleeful satisfaction in ripping off one another. That spring, Truglia had paid $30,000 for some of the guys to arrange a VIP trip to the Coachella music festival in California, only to have them withhold the address of the opulent house that came with it. He'd been left without a place to stay, the others taunting him with tales of how the rapper Post Malone and the model Hailey Bieber stopped by the house for an after-party. More recently, David had brokered a deal for one of the crew to buy Truglia's Bentley, only for Truglia to take the payment and keep the car. David was also secretly recording their conversation on his phone that night in Truglia's apartment. As they talked, he steered the conversation toward the origins of Truglia's money. He'd heard Truglia boast about SIM swapping, and about a different crew he socialized with online. David would later swear in an affidavit that Truglia had even taken him to an AT&T store and tried to get an employee to do a SIM swap right there. It had failed, David recalled, only because Truglia wasn't willing to pay the outstanding balance on his target's account. "Who was the biggest guy you SIM swapped?" David can be heard asking on his recording from Truglia's apartment. "The guy who is suing AT&T?" "Michael Terpin," Truglia said. The memory made him laugh. "He was having a fantastic day. He went to bed thinking 'Wow, I had $24 million in this account,' " Truglia said. "That was funny." At other points in the conversation, his swagger evaporated. "I feel like some people are only my friends because they feel bad for me," he said after a pause in the discussion. "Yeah, I do feel bad for you," David said, "because you're a suicidal loser and just f--- people over." (Truglia had expressed suicidal thoughts in the past.) "I'm not a bad person, though," Truglia responded. "You are a bad person," David said. "Really?" Truglia asked. *** As the hackers and their friends spent Terpin's money, Terpin was doing everything he could to bring attention to his legal crusade. When he filed his suit, he gave an exclusive story to Reuters and penned an open letter to the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, proposing that the government require cellphone companies to conceal customer passwords and PINs from rank-and-file employees. Terpin started getting tips. He and Maxine would be awakened by calls from untraceable numbers at their terraced hillside mansion in Puerto Rico, where they keep their primary residence for tax reasons. Some of the callers disguised their voice with audio processing tools, though Terpin remembers that one kept moving his mouth away from the phone to talk to someone else, revealing an Irish brogue. Terpin made it clear to the tipsters that he was happy to pay for solid information. One of the callers was a man with an English accent who introduced himself as Sauce. Sauce said he belonged to the Community, a group of teenage SIM swappers in the US, the UK and Ireland. He told Terpin that two members of the gang, Nick Truglia and Joseph O'Connor, were the ones who'd robbed him. Some corroboration arrived in December 2018, almost a year after the hack, when David reached out to Terpin over email. He said that he'd made hours of recordings of Truglia in hopes of clearing his own name in the matter of the missing electronics, and potentially incriminating Truglia himself in case he pressed charges. (Truglia did do so, implicating David and three others, though the charges were eventually dismissed at the request of prosecutors, and the case was sealed.) A few weeks after getting the email, Terpin flew David to Puerto Rico and put him up in a Hilton hotel. Terpin and his lawyers were amazed at what David had brought them. In the recordings, Truglia walks David through his method of enlisting phone company contractors in Asian call centers to swap numbers for him. He would call pretending to have an issue with his phone, then ask whether the contractor he was speaking with would like to make some money. The person would often oblige, and Truglia would start communicating with them over Facebook or another social network to direct the number changes. He joked to David about a contractor in India who was fired after doing multiple jobs for him. After listening, Terpin and his lawyers persuaded David to sign an affidavit. Then they filed a lawsuit against Truglia and turned the recordings over to the FBI. But around then, from another caller, Terpin heard a new name. The caller said he was Joseph O'Connor, whom Sauce had identified as a ringleader of the 2018 hack of Terpin. His Liverpudlian accent was audible through the voice-disguising app. O'Connor said he wasn't the person Terpin should be after, and neither was Truglia. The real culprit was someone named Pie, a feared figure who'd been professionally hacking since he was in puberty. After taking some time to think it over, O'Connor texted Terpin a name and hometown: "Ellis Pinsky, Irvington." *** "I had my social group. I ran track, I played soccer," Ellis Pinsky says of his life as a high schooler in Irvington, New York, an affluent bedroom community 25 miles north of Manhattan. "Then I'd come home and get online." At first, that meant playing Call of Duty, but by 15 he'd transitioned to hacking. He'd stay up late, peering into the three monitors set up in his room, then struggle to stay awake the next morning at school. "That was definitely the focus," he says of his nighttime activities, "or, you know, the thrill of my life." Pinsky is explaining all of this over a steak souvlaki in Irvington, at a Greek restaurant with views of the Hudson River. Now 21, he orders a glass of Montepulciano D'Abruzzo. "I viewed it as a sort of puzzle to see how far I could go," he says. "I enjoyed the problem-solving aspect of it. And I think my brain wasn't developed enough to realize, 'This is really freaking wrong.' "  Pinsky, who engineered the original heist. Photographer: Evelyn Freja The members of the Community originally came together on a web forum called OGUsers, dedicated to the unlikely topic of online usernames. To a certain sort of gamer, having a particularly cool handle in a multiplayer game or for your social media accounts—@anonymous or @evil, say—confers status, and the most desired ones fetched tens of thousands of dollars on the forum. Or members could just take them for free, by hacking into the owner's account to steal them. A subset of the community dedicated itself to developing techniques to do this. Some of them branched out into hacking celebrity social media handles, to troll or swindle the accounts' followers. Kids who found their way into this world often underwent a kind of cybercrime apprenticeship, learning the craft and becoming inured to lawbreaking. Today, recruitment ads on hack forums, Discord servers and Telegram Channels offer $100 a day for entry-level cybercrime labor, according to Allison Nixon, the chief research officer at cybersecurity company Unit 221B, who's been researching the Community for more than five years. The jobs include waiting on hold for customer service reps, or, because minors are harder to prosecute, providing the device the target's number is swapped onto, in case investigators manage to trace its location. Pinsky's entry point was playing Call of Duty online, where he was introduced to a user named @Ferno, who he learned was a hacker. Ferno impressed Pinsky with his ability to get whatever he wanted on the internet. Pinsky started doing menial tasks for Ferno, whose true identity he says he still doesn't know, gathering information that would be useful to target someone for identity fraud or to break into their accounts. He also began teaching himself to code in Structured Query Language, so he could break into companies' databases and steal employee data. He found a niche selling information from those networks on the private message service XMPP, bantering with criminals there in the fluent Russian he'd learned from his mother, a doctor who emigrated from the Soviet Union. But Pinsky also learned that getting into someone's social media and email accounts wasn't necessarily a matter of cracking codes. The best way was simply to be let in. Sometimes that meant posing as a service provider to get a user to offer up their own password. Sometimes it meant posing as the person and getting someone at the provider to change it. When Pinsky was 15, someone in his online circle started talking about SIM swapping. The increasing adoption of two-factor authentication—a security measure that requires a second form of identity verification, beyond a password—was making it more difficult for him to use his stolen logins. SIM swapping neatly solved that problem. At first, Pinsky tried doing the swaps by calling cellular service providers, pretending he was the person whose number he wanted and saying he'd lost or just upgraded his phone. To sound convincing, he'd trawl the web beforehand to find the last four digits of the person's Social Security number or the answers they'd given to security questions—information that was often available in hacked databases. Sometimes he'd even call the cell company and pretend to be one of its own employees looking to verify something about a customer. All of that was a lot of work, though, and it often didn't pan out. Pinsky realized it would be far more efficient to enlist someone on the inside, to "reduce the friction," as he puts it now. He wrote a script in the programming language Python to scrape Twitter for mentions of cell service companies by people who worked at one—"You know, somebody saying, 'Oh, just finished my shift at AT&T' or something like that," he says. He turned up plenty. Anytime he found a current employee, he'd contact them to see if they were willing to be bribed. About 10%, he estimates, replied yes. "At one point in time, I had a person at every carrier on my payroll," he says. His roster of so-called plugs brought him cachet. As @Pie, he gloated online about the thousands of dollars he might make with a successful attack. Others in the Community began bringing him targets and invitations to collaborate. On the evening of Jan. 6, 2018, Pinsky received a Discord message from a frequent partner who went by "Harry." The two had never met, but Harry had an English accent and seemed to Pinsky to be around his age. He claimed to live in Spain. Harry told Pinsky he'd found their biggest whale yet. He shared a link on Twitter, and Pinsky checked the man's posts on various social media sites and found a phone number on the many press releases he'd issued. It was Terpin. "He looked like he had some money to take," Pinsky recalls. He says he checked Terpin's number with a plug of his named Jahmil Smith, a contractor who worked at an AT&T store in Norwich, Connecticut, to see whether it showed up in his system. When Smith said it did, Pinsky offered a few hundred dollars—"between $100 and $500," he says—for him to swap the number. The next day, Sunday, Jan. 7, Smith ported Terpin's number from his BlackBerry to an iPhone in the possession of a third Community member known as Cold, who was acting as the "holder." AT&T records submitted in Terpin's lawsuit allege that Smith used a manual override to bypass the six-digit security code that had been placed on Terpin's account after the earlier attack. According to testimony later given by AT&T's asset protection director for Terpin's suit, this wasn't the first time Smith had done this; the company had failed to investigate two prior SIM swaps allegedly involving Smith. And only a week before Pinsky approached him, Smith had enlisted an accomplice to steal six iPhones and around $4,500 in cash from the store he managed. Police reports say Smith admitted to the scheme after CCTV footage showed him pointing out objects in the stockroom to his masked friend. Smith, who isn't a defendant in the lawsuit, couldn't be reached for comment for this article. Once Pinsky had control of Terpin's number, he and Harry got on a Skype call. Pinsky first tried to reset the passwords for Terpin's cryptocurrency exchange accounts but found that Terpin had opted for a form of two-factor authentication that requires a code generated by an app rather than one texted to his phone number. (Security experts recommend that users adopt this practice for sensitive accounts, or else use a physical security key that has to be plugged directly into a device.) Pinsky's next step was to try getting access to email accounts. He figured Terpin would be on Gmail, so he went to Google's account recovery service, which, given a person's name and phone number, returns a list of their Gmail addresses. Pinsky knew Google used text message verification to grant one-time access or reset an account's password. When Pinsky requested a code, it went to Terpin's number, now on Cold's phone. He entered the code and Google granted him access to Terpin's Gmail, where he started fishing around, looking for an email or attachment that might contain crypto wallet passwords. After an hour—at which point the Terpins had likely already contacted AT&T, correctly explained the situation and been placed on an extended hold—Pinsky still hadn't found anything. Then he spotted an email that indicated Terpin had used Microsoft's OneDrive cloud storage service, too. Pinsky went to the Microsoft login page and chose the password reset option. The security code showed up on Cold's phone, and Pinsky typed it in. (Terpin says he'd set up a security app for two-factor authentication on that account, but that it sometimes failed to work. Microsoft Corp. declined to comment.) There, in the trash folder of Terpin's Microsoft cloud storage account, Pinsky found a document listing around a dozen types of crypto wallets. After each was a random string of words. Pinsky recognized them as seed phrases, a common type of access code in crypto. Users are typically cautioned to record them offline in hard copy. Using the seed phrases, Pinsky and Harry got the Steem, Skycoin and Triggers wallets open. *** Neither hacker had heard of Triggers before, but when Pinsky checked its value online, he was stunned. It was, by multiple orders of magnitude, the biggest score of his career, and at the time the largest take on record for a SIM swap. At first, Pinsky and Harry couldn't transfer the hoard out of Terpin's wallet. Most crypto exchanges didn't support Triggers. One of the few that did, Binance, didn't allow minors such as Pinsky on its platform, and it required anyone creating a new account to provide government ID. So the two hackers decided to form a crypto bucket brigade. Pinsky put out a call on a private Twitter account to see who in the Community had a Binance account. Nick Truglia was one of the people who came forward. Pinsky convened a group of eight on a Skype call and deposited a small amount of Triggers in accounts belonging to each of the volunteer mules. Then he asked them to convert it into Bitcoin, minus a small cut, and send it to a third wallet that Pinsky and Harry controlled. One of the volunteers, who was under 18 but had used his mother's identity to open his account, sent some of the Bitcoin to the wrong wallet. Pinsky threatened him so violently that the boy filed a police report afterward. When it was Truglia's turn, Pinsky deposited around $30,000 worth of Triggers, and Truglia sent back the Bitcoin. Then they went to $100,000. When the amount jumped to $800,000, however, Truglia didn't send anything back. Pinsky prodded him, and Truglia made a feeble excuse: He had to go the gym, he said, and wouldn't be back for a while. Pinsky quickly realized he'd been had. Swallowing his pride, he carried on with the transfer process. By the time it concluded, the group had $15 million to $20 million in Bitcoin, and the price of Triggers had collapsed, never to recover (though, given the trajectory of other niche coins in recent years, it's unlikely they'd have remained near their early 2018 peak). Most of the money, according to Pinsky, was split between him and Harry. The feeling, Pinsky recalls, was akin to vertigo. "At one point the fear of the consequences kicked in," he says. In the weeks and months that followed, he withdrew around $100,000, which he kept in cash, and he also bought a $50,000 Patek Philippe Nautilus wristwatch—as an investment, he specifies, "I didn't wear it to school or anything like that, obviously." He says it was his final hack: "I just felt like I had beat the game." A month or so later, Pinsky and a friend from school took a train into Manhattan, where Truglia met them at Grand Central Terminal. Truglia had contacted Pinsky online, hoping they could put the $800,000 behind them. To make amends, he'd invited Pinsky to party with him and his nightlife friends. Pinsky hadn't felt in a position to be moralistic about theft, and he didn't get many invitations like this one, so he accepted. Truglia took Pinsky and his friend back to his apartment, where Pinsky recalls seeing lots of drugs and cash. Later they hit the Up&Down, where they were ushered into the low-ceilinged club surrounded by young women Truglia knew. Pinsky says he felt awkward for much of the evening. In a photo taken that night, he self-consciously grips a bottle of Dom Pérignon while a trio of gamines flank him and mug for the camera. Pinsky and his friend took a cab back to Irvington at about 3 a.m. They told their parents they'd decided to come home early from the sleepover where they'd claimed to be. Months passed. Then, after Christmas 2018, Pinsky's mom received an email from Terpin's lawyers. She read it and asked Pinsky what was going on. "We mutually decided," Pinsky recalls, "that I needed a lawyer."  Truglia, who took $800,000 from the thieves. Photographer: Sasha Maslov for Bloomberg Businessweek Unlike Pinsky, Truglia didn't step away from cybercrime after the Terpin hack. According to prosecutors, in the following months he started his own raft of SIM swaps. Several of his alleged victims lived in northern California, a place with a high concentration of crypto investors and the home of a special Santa Clara County cybercrime task force called the Regional Enforcement Allied Computer Team. Investigators with React soon identified Truglia and began compiling evidence against him. Some of that evidence came via the crypto exchange Coinbase, which notified law enforcement officials that in May it had received an anonymous tip that one of its users was going to try to break into the account of another user, who'd recently died. The company froze the account. When it received a request for access to the account, it required, for extra security, that the person logging in share their identification and a photograph, which the person did; Coinbase also saw that the device used to make the login attempt subsequently got access to Truglia's account. The image the user had submitted was determined to be of Truglia, holding a fake ID card with his picture alongside the name of the deceased. Around 8 a.m. on Nov. 13, 2018, Truglia woke to the noise of pounding on the door of his apartment. One of the pranks members of his online circle enjoy pulling on one another—along with tricking, defrauding and reporting one another to the authorities—is "swatting," a form of harassment that involves making hoax 911 calls to get police to show up, heavily armed, at someone's home. That's what Truglia assumed was happening that morning.  Court filing with images Truglia sent to Coinbase to verify his identity. He had multiple fake IDs. Source: Superior Court of California/County of Los Angeles The officers, however, weren't there because of a prank. They arrested Truglia. A month later he was flown, handcuffed, across the country to Santa Clara County. Erin West, a deputy district attorney attached to React who'd previously helped secure convictions against four SIM swappers, charged Truglia with 21 felony counts related to the theft of more than $1 million worth of cryptocurrency. Truglia was sent to the Elmwood Correctional Facility in Milpitas, California. After he'd been booked and read his rights, Truglia gave a statement in which he admitted to SIM swapping, according to a police affidavit, but he later pleaded not guilty to the charges. In April 2019, Truglia's situation worsened. The Los Angeles Superior Court ruled for Terpin in Terpin's lawsuit against him. Terpin had sought $75.8 million under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, an organized crime law that, in civil suits, allows victims to recover triple the damages they're found to have suffered. With the RICO judgment, Truglia now owed Terpin that entire amount, despite both Truglia and Pinsky claiming that his take from the theft was only the $800,000 he'd pilfered from the two primary thieves. Seven months later came another indictment: The FBI's investigation into Truglia's use of his Binance account to convert Terpin's stolen crypto resulted in federal wire fraud conspiracy charges in the Southern District of New York. Truglia was arrested and arraigned on these charges in New York on April 15, 2020, just days after being granted bail in California. A judge ruled that Truglia could await his federal wire fraud trial under house arrest at his father's home in an upscale gated community in Orlando. He had to stay home, off the internet and away from the Community. But he couldn't stay offline. Members of the Community saw that he was posting on Instagram, and they swatted his dad's house—at least 12 times, by Truglia's count, in the ensuing three years. In December 2021 police officers, on one of their visits, found laptops, iPhones and 7 grams of cocaine that Truglia says belonged to a friend. A judge sent him back to jail in Newark, New Jersey. He eventually pleaded guilty to the federal charges. He was sentenced the following year to 18 months and was told to pay Terpin the first $20 million of what he owed, getting out a month later with time served. "Despite their wholesome appearances," Terpin's complaint read, "Pinsky and his other cohorts are in fact evil computer geniuses with sociopathic traits" "I think a lot of people can relate to seeing something on the internet and wanting it," Truglia says of what drove him. "Like, wanting the attention or what someone else has or whatever. And mainly I think it was that." He's talking about this in a room at the Soho Grand Hotel, in downtown Manhattan, in early April 2023. He's out of prison and in town for a quick visit. The pair of chunky-soled Rick Owens boots he wore to go out the night before lie on the floor of his room, and he recently woke up from a nap. He seems to find the sun painful. "I had some possessions here that I needed to have returned to me," he says cryptically, sitting on a window ledge. Earlier in the day, according to Terpin's lawyers, Truglia spent about five hours with one of them, working on converting some of his crypto and jewelry into cash to pay Terpin. (Truglia could be held in contempt and sent back to prison if he fails to do so.) He and the lawyer went to banks where Truglia had safety deposit boxes and had visited an acquaintance Truglia had entrusted, before being incarcerated, with a piece of paper with one of his cryptocurrency keys written on it. It seemed the person wasn't giving it back. On May 9, weeks after his New York City jaunt and while still on supervised release, Truglia was arrested again in Orlando. Overwhelmed by his legal struggles, he'd texted an acquaintance a picture of a gun, threatening to use it on himself. When the police showed up to check on him, they found ammunition (which Truglia's father has since said belongs to him) and some of Truglia's fake IDs, but no firearm. Nonetheless, he was charged with possession of a concealed weapon by a convicted delinquent, as well as four counts of fraud. He was sent to a holding facility in Oklahoma, then called before a federal judge in New York City for breaking his probation. On top of all of this, at some point he'll have to stand trial in California. *** Other members of the Community are also facing legal consequences for their actions. In an unrelated case, Joseph O'Connor pleaded guilty to participating in the hacking of more than 100 Twitter accounts, including those of Joe Biden, Elon Musk and Barack Obama, as well as to cyberstalking and SIM swapping female celebrities to blackmail them. He was sentenced to five years in prison. As for Harry, he might still be at large, if he's not one of the unlucky hackers who've been arrested and tried for some crime or other. But the Community, according to cybersecurity researcher Nixon, continues to grow. Those who remain from the old guard are adults now, bringing a new crop of kids into their ranks. "A lot of the people that get caught still are children, and the adults running things in the background are like the puppet masters," she says. "When the child gets picked up, they know that they need to melt away into the background." Pinsky himself has avoided criminal charges, a topic he largely avoids in conversation. It probably helped that he was underage during his cybercrime phase. It also helped, he admits, that he and his lawyers assisted law enforcement and that, after Terpin found him, Pinsky turned over what he says were his remaining proceeds from the hack: the $100,000 in cash, the watch and the remaining Bitcoin. When he gave it to Terpin, the Bitcoin had lost roughly half its value since the hack. Like the Patek Philippe, it has since appreciated nicely. Terpin, however, didn't think the two were square, and when Pinsky turned 18, Terpin sued him. "Despite their wholesome appearances," the complaint read, "Pinsky and his other cohorts are in fact evil computer geniuses with sociopathic traits who heartlessly ruin their innocent victims' lives and gleefully boast of their multi-million-dollar heists." Terpin talked to the New York Post, calling Pinsky "Baby Al Capone" in a story that ran with the photo of Pinsky at 15 at the Up&Down club. Two weeks later, four armed, masked men broke into the Pinsky home in Irvington in the middle of the night, presumably believing—as Pinsky had once assumed of Terpin—that the teen had some money to take. Pinsky had recently bought a shotgun for protection. In a Rolling Stone profile published last year, he described how he, his mother and younger brothers, alerted by their home security system, sheltered upstairs with the weapon until police arrived and thwarted the invasion. Two of the men escaped. Pinsky is at New York University now, studying computer science and philosophy. This summer he's taking extra classes and interning with the software engineering team of a venture capital firm. He wants to graduate early. In October 2022 he agreed to a court judgment requiring him to pay Terpin $22 million in damages on top of what he'd handed over three years earlier. Pinsky has plans for startups and has already developed a productivity app that forces users to pay a fine if they don't complete a task in time. To further placate the man he robbed, Pinsky also agreed to give a deposition in Terpin's suit against AT&T. It may not entirely have helped, though. Under questioning, he readily conceded that he had never been able to steal cryptocurrency "just by conducting a SIM swap." The swap itself was simply the first step, and if the intended victim used strong multifactor authentication, or stored all their crypto credentials offline, there wasn't much Pinsky could do with the stolen phone number. AT&T ended up using part of Pinsky's deposition in its defense. In response to detailed questions for this story, an AT&T spokesperson said in a statement, "Fraudulent SIM swaps are a form of theft committed by sophisticated criminals. We have security measures in place to help defeat them, and we work closely with law enforcement, our industry and consumers to help prevent this type of crime. It is unfortunate that these criminals targeted Mr. Terpin, but we would note that the court agreed that we were not responsible for Mr. Terpin's losses." This March, nearly five years after Terpin filed his AT&T suit, a federal judge in California essentially threw it out. AT&T wireless customers sign a contract that, among other things, limits the company's liability for losses and damages. The agreement also explicitly warns that the company can't guarantee the security of a user's personal information. In signing his user agreement, the judge wrote, Terpin had agreed to those terms. The judge added: "Terpin and AT&T did not agree that, should a third party bribe a retail employee to SIM swap Terpin's phone number, then hack Terpin's email and online accounts, root through Terpin's digital garbage to discover an unknown cache of cryptocurrency access credentials, and ultimately use those credentials to steal millions in cryptocurrency, AT&T would be liable for Terpin's loss." AT&T, he ruled, didn't owe Terpin a cent. Terpin, who estimates he's spent more than $5 million on legal fees thus far, has filed a notice to appeal. He and his lawyers argue that the judgment sets a dangerous precedent and allows cellular companies to keep ignoring the security concerns that hacking and identity theft victims keep trying to raise. Pinsky is sympathetic to the argument. "It's the company's job to protect the security of their customers," he says. "Whether that's a bank, whether that's a phone company—security is their job." Truglia is more philosophical. The question of ultimate responsibility, he suggests, is a tricky one. Speaking in his New York hotel room before his reincarceration, he's not sure how much responsibility cellphone companies have for preventing SIM swapping. He does agree that it could be made more difficult. "There should," he suggests, "be some technology they can use."—Margi Murphy and Drake Bennett, Bloomberg |

No comments:

Post a Comment