| Five Months Predictions are difficult. Yes, particularly when they concern the future. And in markets, perhaps it's fair to add they're really hard to make over a relatively short timescale. Are longer-term predictions safer? The question arises after last week's regular update of Wall Street's strategists' forecasts for the S&P 500 at the end of this year, conducted by Bloomberg's Lu Wang. Almost all have been forced to raise their targets after a first half rally that took most everyone by surprise. But even after doing this, the great majority of big Wall Street strategists are implicitly predicting a terrible time for the stock market over the rest of this year. This is what their targets imply for performance until Dec. 31, based on Friday's close: It's not that they all think we'll soon have a major slide. Rather, they are chasing a market higher, and left in an untenable position — and judging by the comments since our piece came out last week, there's a lot of derision out there. Against that, all of investing is about gauging the risks and opportunities of the future. You have to have a view. The problem with the annual round of year-end predictions is that it's impossible to call a market number on a precise date in the future. What's more useful is to work out assumptions about the world, and offer a model about how this will affect the market. You can put a number on what that implies for the next year, but that need be no more than the checking process. If it turns out that number is wildly higher or lower than it is now, then it's a good prompt to retest assumptions. But predictions for a given date not far off make no sense. The numbers above reflect the belief among strategists that equities look overvalued relative to their history and to other asset classes. I think they're right about this. But overpriced securities can easily get even more expensive. Converting a model that says the stock market is too expensive into a prediction of a big fall over the next five months won't wash because there's nothing about timing in the model. Big market moves generally need a catalyst. This could come from a number of things (whether external events like a pandemic, or financial events like a wave of bankruptcies or a decline in profits), but the strategists aren't making predictions about them. Neither should they. In the short term, it's also obvious that the strategists, and the world of institutional investment in general, are out of sync with retail investors. Last week's publication of Bank of America Corp.'s regular survey of global fund managers found that asset allocators are generally negative. Meanwhile, the respondents to the American Association of Individual Investors' weekly survey are close to their maximum bullishness about stocks. The latter would in normal circumstances be a good signal to sell — but the doubts of the big allocators counteract that: Institutions' bearishness is a big component to this market rally, then. They're more circumspect because they're looking at longer time horizons (or at least trying to), which warn against being heavily invested in stocks. Let's go through some longer horizons in turn: Three Years If we look out to three years, JPMorgan Chase & Co. recently revised its capital market assumptions, used as an aid in asset allocation. The idea is that while making decisions, its managers should always recall where the world is heading. At present, the exercise reveals what it calls "a dislocation of the long- and short-term view," with historically dependable recession signals looming in a benign market environment.

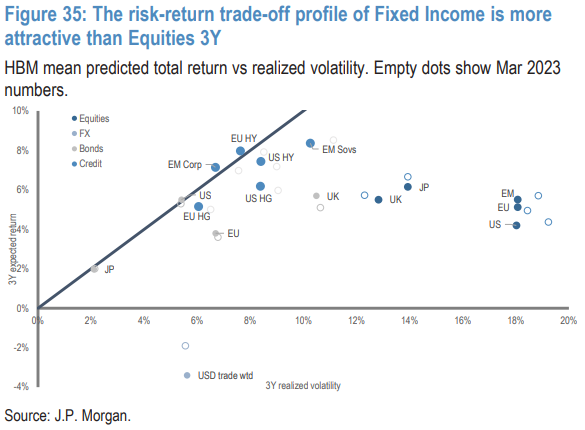

Over three years, those assumptions suggest that the US stock market isn't going to do anything too exciting, with the realized volatility for equities way too high to put up with for the predicted returns. Over that period, using a Bayesian approach to adapt from past experience, the most attractive returns are in European and emerging market credit:  So, if JPMorgan has this right, fixed income offers "returns that range from comparable to higher than equities, but for half the volatility." Thomas Salopek, head of cross-asset strategy, also reckons that over the medium term, factors that have been historically dependable will continue to be reliable: Rate hiking cycles are generally followed by weakening GDP growth with varying degrees of lag, and much more often than not, recession. Falling margins and profitability have resulted in rising unemployment. And a tight risk premia, in particular at the end of the cycle, pushes us to allocate toward safer assets.

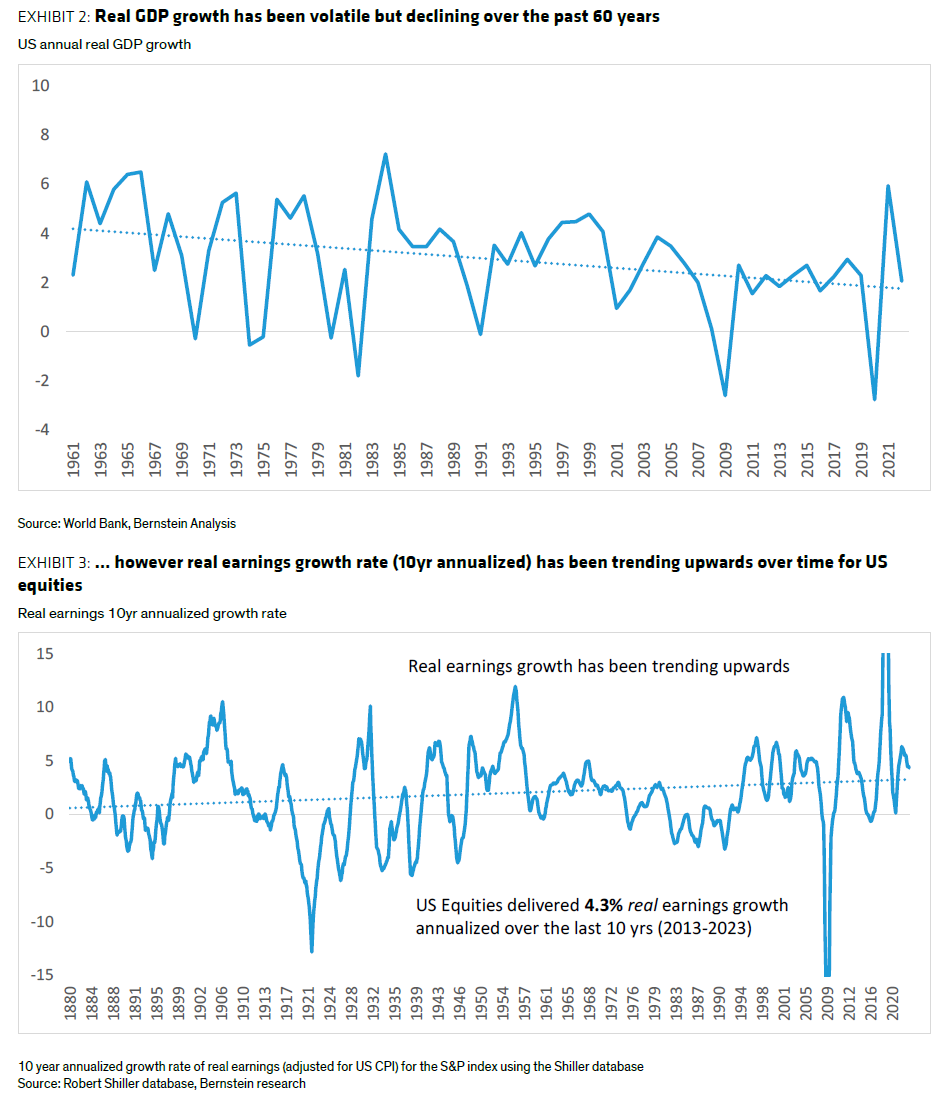

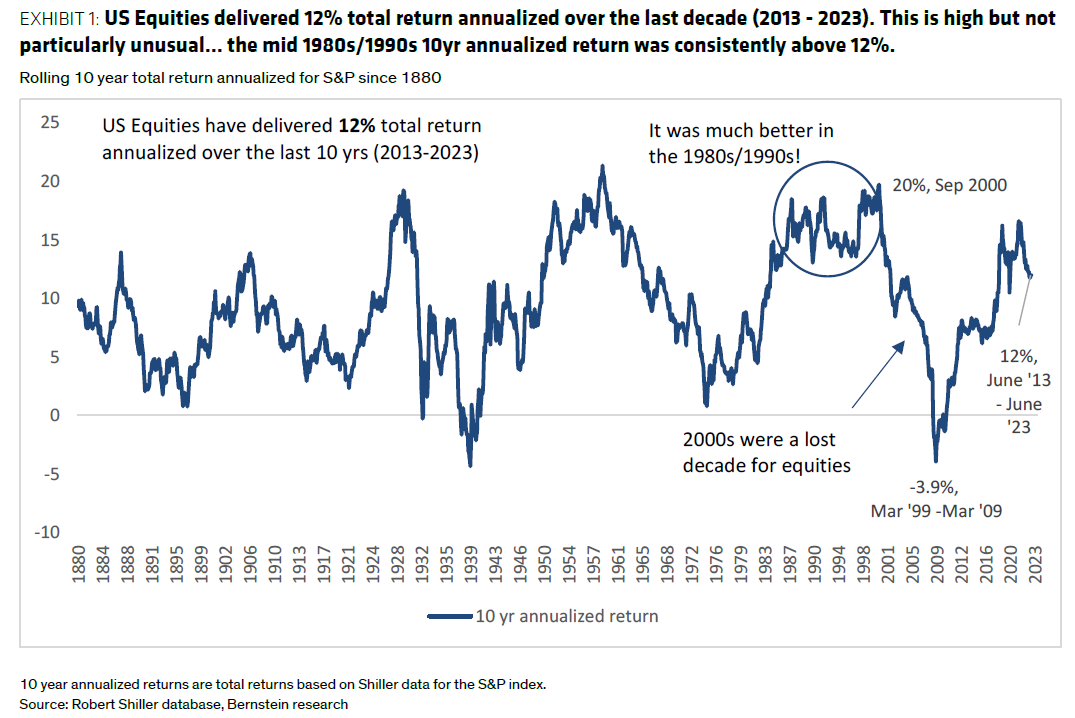

All of this is true, but it does make life painful when, as now, the Dow Industrials has risen 10 days in a row. Seven Years Taking a longer frame, the Boston-based fund manager GMO regularly updates its seven-year projections for real returns. The philosophy, derived from GMO's founder Jeremy Grantham, is that mean reversion is among the most powerful forces in finance. On that basis, after the heady returns of the last few years, virtually nothing is going to perform as we've come to expect over the next seven years: Yes, GMO expects US stocks to lag inflation over the next seven years. If you want the kind of return that you've come to expect from US stocks, you need to go hunting for bargains in emerging markets, according to their framework. Meanwhile, GMO expects US cash to make a 1.7% real return on average, and outperform the stock market over seven years. That's alarming, and Grantham's view that a super-bubble is in the process of popping. 10 Years The longer you look into the past for patterns, and the longer the term ahead that you try to predict, the safer predictions become. Sarah McCarthy and Mark Diver of AllianceBernstein last week published Long View: Return prospects over the next decade using 100 years of data, a study that makes this point beautifully. The highlights are as follows. Not all things are constant. Financial systems and economies tend to move in long cycles. As Bernstein notes in this fascinating treatment, economic growth in the US is steadily slowing over time, while profit growth is steadily rising. The cycles make it hard to see but the trends exist:  With earnings growth trending upward — possible causes include technological advances, the decline of organized labor, and greater tolerance for concentration and monopolies — it makes sense that earnings multiples might rise over time. As the charts also make clear, however, any attempt at valuation needs to correct for the economic cycle. That's typically done by using a "cyclically adjusted" price-to-earnings multiples over the previous 10 years, as first suggested by Benjamin Graham, and made very popular by the Yale University economist Robert Shiller.CAPE proves to be useless for timing, but great for predicting 10-year returns. As the Bernstein team shows, 10-year returns from US equities have on average been fantastic, but extremely variable:  For those who wonder why such a fuss is made of CAPE, this is how it has moved, along with subsequent 10-year returns, since 1880. It's a startlingly strong predictor. And it implies we have a 4% annualized return to look forward to over the next decade: By historical standards, 4% is poor, but also not disastrous. Given the amount of growth that has been taken on faith in the post-pandemic excitement, it also seems reasonable. Even if investors are right in their assessment of the prospects for Nvidia Corp. and other stocks that tend to benefit from artificial intelligence, a lot of the gains have already been made. When judging bonds, the best predictor of future returns is the current yield. This is how the 10-year yield has fared at predicting the subsequent 10-year total return, going back 150 years: As with stocks, the next 10 years seem clearly defined by historical precedents. Unlike stocks, the cataclysm of the last 18 months as inflation returned has turned things around and implies a 3.5% return for the next decade. That is still less than the simple model predicts for stocks, but the gap is its narrowest in a while. And, of course, bonds carry a lot less risk. This kind of logic probably helps to explain how fund managers have grown uncharacteristically bullish about bonds. According to BofA, they are overweight in bonds for the first time since the Global Financial Crisis climaxed in 2009, at which point fixed income was outperforming. Now, they are following the logic of mean reversion and loading up with bonds after 18 months of historically terrible performance: But Bernstein's study certainly doesn't say that an all-out crash is imminent. The longer the rally goes on, the greater the chance that a crash will be needed, but it's not of help with timing, and it suggests that equities will do a bit better than bonds over the next decade once the dust has settled. So there's the logic that has entrapped the community of strategists and asset allocators, and in the short run may well lead them to add yet more fuel to the stock market's ascent. —Reporting by Isabelle Lee The week ahead will be dominated by the "Big Three" — the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan — who have monetary policy meetings before what we can all hope will be the doldrums of August. There'll be time to return to that tomorrow, but it's worth pointing to one central bank event that might just bulk as large as any decision on interest rates. On Tuesday, the ECB publishes its Bank Lending Survey for the third quarter. The last one, after the March banking excitement, saw credit conditions at their tightest since the Global Financial Crisis — although banks did expect an improvement in the second quarter. This survey could be key to confirming whether it really is safe to put the crisis four months ago behind us. Deutsche Bank AG sees "risks tilted to an underperformance" compared to banks' expectations in the last survey. Then on July 31, the Fed will publish the SLOOS (Senior Lending Officer Opinion Survey), which briefly took over as the world's most closely watched economic metric in the immediate aftermath of the bank failures. It's important to watch. If banks help do the Fed's work by tightening lending standards as rates are rising, it's very difficult to engineer a soft landing, as this chart from JPMorgan shows: Banking stress was seen as likely, and as a game changer, in early spring. It would be nice if these surveys proved that judgment wrong. Rain stopped play. A couple of weeks ago, I discussed that many from non-cricketing nations find it hard to work out how anyone can appreciate international cricket matches, in which it's possible to play for five days and not achieve a result. It's also at the mercy of the elements. I'm now fully appreciating the problem. England can no longer win the five-match series against Australia after near-constant rain in the last two days (in notoriously rainy Manchester) meant only two hours of play were possible, out of the usual 12. Unlike in baseball, it's not possible to suspend the game and come back later. Rain is allowed to stop the game (at a point when England, 2-1 down in the series, were well ahead). Hmph.  Before the English weather gets bashed too much, this was Adelaide in 2010. Photographer: Hamish Blair/Getty To feel a little better, I tried listening to some songs about rain. There are a lot, and many of the videos that follow are, in my opinion, really good. Of course, there is Prince's Purple Rain. Try William It Was Really Nothing by Manchester's The Smiths ("The rain falls hard on a humdrum town/This town will get you down"), I'm Only Happy When It Rains by Garbage, Why Does It Always Rain On Me? by Travis, Rain On Me by Lady Gaga and Ariana Grande, I Can't Stand the Rain by Eruption, (or Ann Peebles, or Angeline Ball of The Commitments, or Missy Elliott, or the late Tina Turner), Rain by The Beatles (analyzed here for those interested in their middle period), Rain by the Boomtown Rats (which was called "Dave" in the UK but mysteriously retitled when it was released in the US), A Hard Rain's A Gonna Fall by Bob Dylan (beautifully covered by Edie Brickell), Raindrops by Ariana Grande, Singing in the Rain by Sheila B. Devotion, Singing in the Rain by Gene Kelly, Rain by Madonna, The Rain Song by Led Zeppelin (the video starts with Robert Plant talking to the audience as they fix a technical problem), Red Rain by Peter Gabriel, November Rain by Guns 'n Roses, Here Comes the Rain Again by The Eurythmics, It's Raining by Darts, I Wish It Would Rain Down by Phil Collins and Eric Clapton (who gets a double for Let It Rain), Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head by B.J. Thomas from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, or also by Manic Street Preachers, Raining In My Heart by The Cranberries, It's Raining Men by The Weather Girls (later covered by Ginger Spice, Geri Halliwell), Raining Men by Rihanna and Nicki Minaj, Raining Tacos by Parry Gripp and BooneBum, Raining in My Heart by Buddy Holly, Rainy Night in Georgia by Randy Crawford, Wake Me Up When September Ends by Green Day. If you need a drink of cool, cool rain, The Who can mix one up beautifully. And you have to give a special shoutout to Creedence Clearwater Revival's bookends on the world's troubles in Have You Ever Seen the Rain? and Who'll Stop the Rain?. Who indeed? Well, Jimi Hendrix made a point of saying it wasn't raining where he was. Any more songs for a rainy day out there? Congratulations to the Aussies, I suppose. Have a good week everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment