| Was there ever any doubt? Wall Street awoke Monday to the news that First Republic had been seized by the government, and the bulk of its business taken on by Jamie Dimon's JPMorgan Chase & Co. The man has been a dominant figure on Wall Street for a quarter century, and judging by the market reception, he has delivered again, both for his own shareholders and for everyone else. Investors certainly think that JPMorgan has got itself a good deal. Its stock gained 2.14% while that of PNC Financial Services, its main rival for First Republic, dropped 6.33%. That continued a pattern seen since Dimon took over the bank at the beginning of 2006. This is how JPMorgan's share price has quadrupled in the period, while the larger US banks as a whole have slipped slightly: "Our government invited us and others to step up, and we did," Dimon said in the press release announcing the transaction. That was nice of him. It all sounds a lot like his predecessor J Pierpont Morgan, founder of the bank that bears his name, who more than a century ago saved the banking system when the government was incapable of doing so. And it does raise the question of how much we've really progressed since then. I'm assuming most readers will already know the broad outline of the second-largest bank failure in US history. If not, Matt Levine's superlative explanation is here, JPMorgan's own slide presentation is here, and Bloomberg News' masterly Big Take on how First Republic's jumbo mortgage business brought it down is here. If you'd like to diversify, then there's plenty of weighty reporting from the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and the New York Times. All of this should bring you up to speed on how First Republic failed, the deal that was struck, and the reasons why it's been so well received (in a nutshell, because it's probably going to make lots of money for JPMorgan shareholders). Is there anything about this deal that should worry us? The big are getting bigger. JPMorgan already had more than 10% of US deposits, meaning that it was barred from acquisitions, but its size allowed it to prove to regulators that it could buy First Republic at a cheaper price to the public purse than anyone else. It cannot possibly be allowed to fail. That means it needs to be regulated that much more tightly. Back in 1998, when Travelers Group was about to merge with Citicorp to form Citigroup, with Dimon as its president, the legendary Wall Street economist Henry Kaufman warned that the vast new banks would have to become "quasi-public utilities," and accept public regulation that would make them "too good to fail." A financial system patrolled by a few institutions regulated as tightly as water companies would have been "safe;" it wouldn't have been dynamic, and would have shrunk from taking the risks that help to grow an economy. At this point, JPMorgan is acting as a public utility, saving public money when it rescues troubled banks. It also has advantages with which even huge regional banks like PNC cannot compete. At present, deposit insurance is capped at $250,000 per account. Many companies need to keep more than this on deposit (although very, very few individuals should do so). That gives a huge advantage to JPMorgan over smaller regional and local banks that specialize in particular business sectors or geographies. That leads to the following drastic assessment from Robert Hockett, professor of law and finance at Cornell University: We now have but two choices before us: either we preserve our production-focused regional and sector-specific industrial banking systems by removing Federal Deposit Insurance limits immediately, or we allow financialized Wall Street banks to take all — an outcome that will ultimately necessitate nationalization of the whole sector.

That is the choice that the world has been ducking, at least since Dimon helped to create Citigroup in 1998. Hockett hopes to avoid it with legislation that would raise insurance caps for specific business accounts. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation itself seems interested, and the idea has bipartisan support in Washington. This can be viewed as a further shift toward nationalization, in an attempt to accommodate the power accreted by JPMorgan. Beyond that, there is an echo from a far earlier crisis: The Panic of 1907. You can read about it here, and in this great book. Confidence in a range of large banks collapsed. With no central bank, it fell to J Pierpont Morgan to act as a Dimon-like convener, banging heads together and putting money on the table to get people to calm. Crowds gathered in Wall Street and cheered him as he walked from meeting to meeting. The Federal Reserve was founded in response. Politicians decided that bank runs couldn't be allowed to happen so easily, and found it intolerable for the safety of the financial system to rest on one private individual. Morgan was questioned by Congress and offered a soundbite that has lasted more than 100 years. He insisted that personal trust, not money, was the basis of the system: A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom. I think that is the fundamental basis of business.

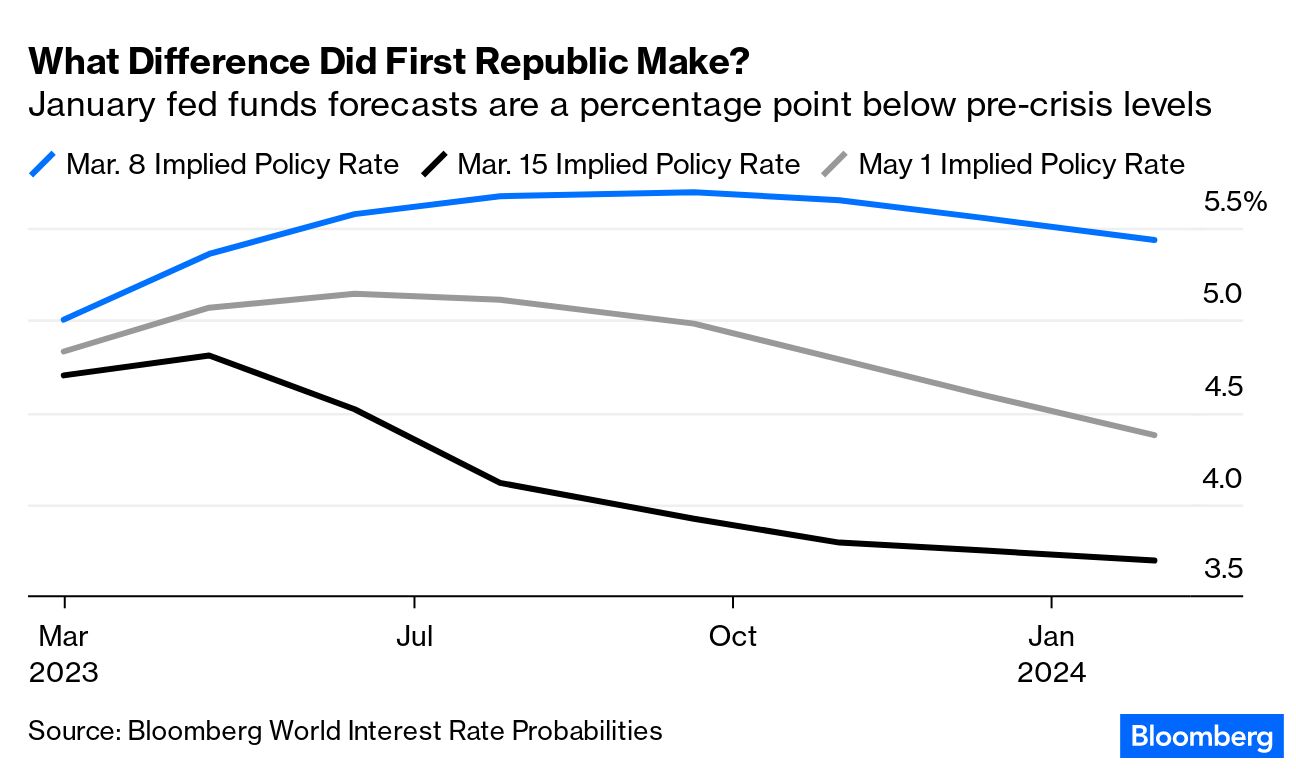

The financialization and transfer of power from bank-lending officers to markets has made it harder for anyone to work on such a basis. But the centrality of Dimon suggests that personal trust might still matter almost as much as all the bonds in Christendom. That gives rise to the same concerns that Morgan's power created 116 years ago. Dimon's record is at this point beyond question. His bank has had its scandals along the way, but his place in history as one of the most important bankers since Morgan himself appears to be secure. It isn't a criticism of him to question the degree of reliance the world now has both in the giant bank he has built, and in the man himself. Dimon is 67. It will take many years for any successor to build up the kind of trust that has been placed in him. Bank failures matter because of the impact they have on the availability of money. If financial conditions tighten, the economy will tend to slow down (and inflation, the problem of the moment, should moderate). A banking crisis can then be seen as a blunt instrument for slowing price rises. These bank failures have largely been caused by the Fed's rate hikes, which were meant to attack inflation. When SVB Financial crashed in mid-March, it led to an instant change in expectations. In the chart below, compiled from the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function, which derives fed funds forecasts from futures prices, expectations for the Fed's course until the beginning of next year dropped in days from the top to the bottom line. Since then, expectations for near-term rates have risen again, but the projected fed funds rate for next January is still a full percentage point below its level on March 8:  Has the bank seizure really done that much work for the Fed? The best regular evidence on this comes from the quarterly surveys that central banks conduct of banks' senior lending officers. These had shown a perceptible tightening ahead of the crisis. The European Central Bank's next survey is due out today (Tuesday), while the Fed's is also due soon, and will color the Federal Open Market Committee's decision this week. While awaiting these measures, however, there are plenty of others from private-sector researchers that show that money is getting tighter, which I first wrote about in March. The following chart comes from Capital Economics, which recently revamped its financial conditions indexes. They include a range of bond yields and bank and mortgage rates, exchange rates, measures of house prices and equity prices to cover the strength of collateral, an array of volatility indexes and debt spreads, and surveys of bank lending standards. Smooshing them all together, this is the picture that emerges for a host of developed countries over the last 25 years. It was updated after the March banking failures, but before the First Republic sale: During the Liz Truss implosion, British conditions were even tighter than they were in 2008. Across the rest of the world, they're unmistakably tighter than at any time since then. Should we care? Yes. This chart demonstrates that on a global basis, financial conditions measured this way are a great leading indicator of economic problems ahead: This is ultimately why the banking crisis matters. At present, stocks imply minimal damage to the economy, while bonds don't suggest anything as horrible for the economy as the Capital Economics indicator seems to portend. Some degree of harm to financial conditions is inevitable because real losses have been made, and they will ultimately be borne by someone. The money the FDIC is spending on this will ultimately come from other insured banks (making them a little poorer and less likely to lend), defrayed by increasing the costs they charge to their consumers (making them a little poorer and less likely to borrow). That said, while some degree of negative effect is inevitable, it needn't be that serious. CFRA Research estimates that the cost of replenishing the Deposit Insurance Fund could translate to a 14% hit to the banking industry's earnings over one year, a 7% hit over two years, or just below 5% over three years. That would be an unpleasant hit for bank shareholders, but not a game-changing blow to the entire economy. The next evidence on this will be the ECB and Fed lending surveys. In these circumstances, they could scarcely matter more. The political necessity is to deny that this is a "bailout." The term is diaphanously defined, and need not be negative (if your boat is shipping water it makes sense to bail it out, after all), but has become deeply pejorative. No sensible politician of any persuasion would admit to a bailout. What exactly is meant by it? The key charges that any politician wants to avoid are that they have given taxpayers' money to people who don't deserve it, or allowed the people responsible to escape accountability for their actions. The latter issue is vital after the woeful failure to try to prosecute the many financiers who might have been guilty of fraud after 2008. But this time around, the executives appear to have been kicked out, and their shares are now worthless. Further, it's doubtful that they are in much legal jeopardy, as they seem to have done a bad job of managing interest-rate risk, rather than engaging in anything deliberately fraudulent or misleading. It's hard to say they've been personally bailed out. Where the notion of a bailout becomes most plausible is in the treatment of First Republic's deposits. Above $250,000, depositors theoretically know that they're bearing the risk of a default. However, JPMorgan has taken on all deposits, not just the insured ones, and will pay off in full the large banks that joined with it and sank $25 billion into First Republic deposits in a March operation meant to stop a bank run. How can this be justified? Inflicting losses on larger banks would have been a good way to help the crisis spread, so on macroprudential grounds it makes sense to have done this. Allowing them to lose would also have forfeited good will from their executives in any similar future situations. Individuals with uninsured deposits are trickier. Having made depositors of SVB whole in March, the widespread assumption was that the government was now offering an implicit guarantee on all uninsured deposits. There is an argument against, however, as sent to me by a reader before the weekend: Every FRC customer and his mother knows after six weeks of drama that uninsured cash isn't safe, particularly at FRC. $100 billion had left the bank by the end of March, and probably more by now. For reasons known only to them, or for no reason at all, other customers have left $20 billion in the bank. Maybe they hold on because they expect the FDIC to bail them out. This is the very definition of moral hazard. FRC isn't SVB or Signature, nor are its customers like theirs. The feds protected them, deciding to act quickly in uncertainty and to forestall bank runs elsewhere. That's not the case here. Depositors haven't in general pulled their uninsured deposits from other banks.

Therefore, my reader argued, bailing out uninsured depositors at First Republic shouldn't be either necessary or politically acceptable. As is often the case when arguments of moral hazard — the tendency of insurance to prompt people to take risks — come up, I'm tempted to agree in principle, but I don't think it flies in practice. Given that uninsured depositors were rescued in full back in March, they would be entitled to be furious if the government changed its mind this time. They were doing exactly what the government was trying to encourage by leaving their money on deposit with First Republic, rather than adding to a run. Punishing them in those circumstances would have been problematic. Perhaps most importantly, the idea of using bank runs as a way to discipline banks, and relying on depositors to monitor their behavior, died the best part of a century ago. It cannot be brought back. (Although this does raise once more the issue of whether we can continue without explicit deposit insurance, which would entail a form of nationalization.) As to the complaint that there was no point getting banks to put money on deposit with First Republic if the government was always going to bail them out when push came to shove, it bought everyone valuable time. Rather than inflicting another lost weekend in March, First Republic bumbled along for a month, while nerves about the banking system calmed down. When it was finally seized, as we've seen, scarcely anyone seemed perturbed. Alexander Yokum, equity analyst at CFRA Research, defends this as follows: Some may view the March deposit infusion by large banks in FRC as a complete failure, but we disagree. If FRC had not received $30 billion from large banks in mid-March, the bank would likely have failed sooner, resulting in more fear and more deposit withdrawals from other regional banks. This could have caused a series of bank failures that would have weakened the US financial system.

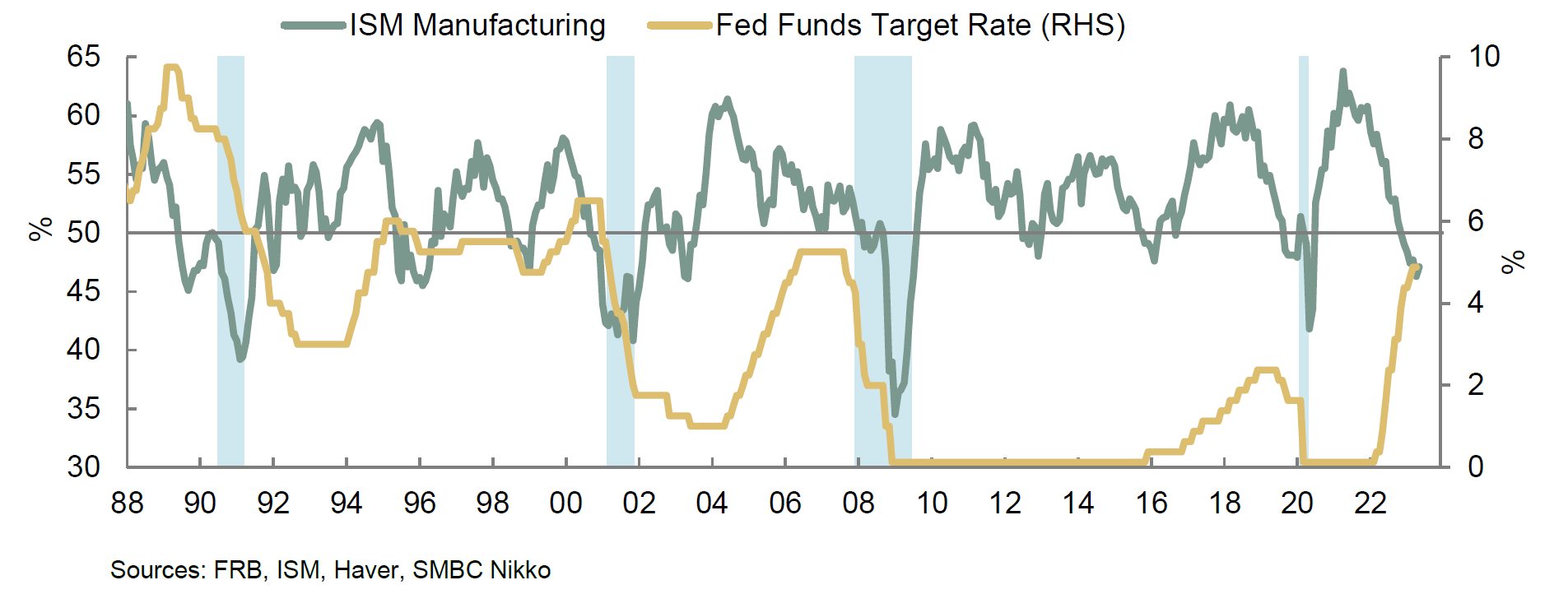

If we define "bailout" as "giving government money to people who don't deserve it," on balance this doesn't qualify. A functioning banking system is a public good, and in this case public money was deployed wisely to maintain it. Rather than argue about the word "bailout," it would be better if everyone could focus on the contradictions in US and European banking regulation, which continues to put ever more trust in a few huge institutions that can't be allowed to fail. A key indicator of the health of the US economy contracted for a sixth-straight month in April, a sign that Fed officials still have a ways to go ahead of their policy meeting this week. That's the longest such stretch for the Institute for Supply Management's gauge of factory activity since 2009, the year of the Great Recession: Put simply: The factory sector remains in recession, wrote Joseph LaVorgna, chief economist at SMBC Nikko Securities. He pointed to the run-ups to the 1990-1991, 2001 and 2008-2009 downturns, all of which saw similar prolonged periods in contraction. "Will this time be different?" he asked. Probably yes. The last few times the ISM had similarly long stretches of underperformance but the economy avoided a recession were in 1995-1996 and 1998. In both cases, the Fed quickly pivoted to rate cuts by reducing the funds rate 75 basis points each time, he wrote. Both times, the Fed changed course due to serious problems in the financial system — the Tequila Crisis in 1995 and the Long-Term Capital Management meltdown in 1998. "Kudos to the Fed," he added. "Unfortunately," the same will not happen this time.  Source: SMBC Nikko Securities Ahead of the May 2-3 meeting, swap traders have slightly upgraded the odds that the Fed will increase its policy rate by a quarter-point. But importantly, many view a hike as the last one for this cycle. If such an expectation plays out, this will bring the funds rate to a range of 5% to 5.25%, which means that in the last 13 months, the Fed will have hiked by 500 basis points, making the current tightening cycle one of the fastest and largest on record, LaVorgna highlighted. In no other six-month (or more) consecutive downtrend of the manufacturing ISM did the Fed hike rates, LaVorgna said. For Will Compernolle, macro strategist at FHN Financial, the ISM will unlikely change the Fed's decision. The Services ISM, released Wednesday morning prior to the FOMC decision, might matter more: Pressures in the goods side of the economy from shifting consumer demand and supply chain bottlenecks continue to subside. The modest improvement in activity and even in employment are not cause for concern. In fact, the Fed's primary labor-market concern is on the services side of the economy.

Barclays Plc economists said the main development was an upturn in the input prices component, which rose to the second positive reading in three months. This suggested that goods prices are still firming: With backlogs receding, it was reasonable to hope that there would be continued deflationary pressure on industrial prices. It will disappoint the Fed that this seems not to be happening. It also seems to have disappointed the bond market. Treasury yields had taken the news on First Republic in their stride, but surged after the ISM data: This is all the more remarkable as the overall numbers were recessionary, suggesting that bond yields should go down, not up. For Jim Baird, chief investment officer at Plante Moran Financial Advisors, the decline in new orders in April reflected soft demand for many goods as does the slide in customer demand: "Consumer spending patterns since 2020 have been unusual since the expansion began. An early buying binge of goods gradually faded as Covid-19 health risks subsided and a growing number of Americans gradually returned to travel and other activities." The bottom line: Manufacturing remains under pressure as consumer demand for goods remains weak — and yet inflationary pressures haven't gone away. Elsewhere, the employment measure rose above 50 for the first time in three months, which will also be an unwelcome development for the central bank as it hopes for a fall in wage pressure. (For a fuller picture of the labor market, the monthly jobs report is out Friday). The week is yet young. — Isabelle Lee This little billet doux from US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to Kevin McCarthy, the speaker of the House, was published just after the market closed. The chicken game over the federal debt ceiling is getting more intense. Prepare to hear about this issue a lot this month: Some more wedding songs: Another One Bites the Dust by Queen, Ball and Chain by Van Morrison. And for some choice best-man speeches, try Benedict Cumberbatch in Sherlock, and Rowan Atkinson (who also does a great turn as the father of the bride). Any more suggestions? Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment