| China is back; its latest economic figures brook no argument. But much more intriguing is the way the nation has managed this recovery compared to previous economic growth spurts in the post-Tiananmen era. Meanwhile, the dilemma that Chinese resurgence is creating for investors and politicians in the rest of the world is excruciating. The headline numbers show that gross domestic product increased 4.5% year-on-year in the first quarter, compared to an expected 4%, while retail sales topped 10%. What was arguably most significant, however, was the way consumption now clearly exceeds growth in fixed-asset investments. China's explosive expansion of the last two decades has been fueled by big outlays going into the latter, eluding officials' attempts to "rebalance" growth toward services and the consumer. At least in the first quarter of this year, it looks like rebalancing has finally happened: These numbers are subject to the caveat that Covid-19 could be distorting behavior, of course. But if so, those distortions have happened in a way that has totally escaped the efforts of economists to keep track in real time. The much-watched Citi index of economic surprises suggests that the latest run of macro numbers have come as the biggest positive surprise since 2006, when conditions were very different: On the face of it, a strong outcome on this scale, so soon after almost all hope had been abandoned, should be enough to drive a big rally in Chinese assets. But the impact of the economic rebalancing can be seen in the way markets are responding. One "tell" of this: Copper and iron ore, which usually spring into action whenever the Chinese economy perks up, have gained a bit since the end of Covid-Zero restrictions, but remain well below their past-pandemic highs. For metals, this is a different kind of recovery: For the rest of the world, a services-driven rebound means fewer spillovers for global demand as Michael Hirson of 22V Research points out. But a gradual firming in China's manufacturing is still welcome, he says, while any evidence of consumer strength reduces the serious tail risk of a recession. Nevertheless, these numbers won't be as well received outside China as might normally be expected. To quote Paul Donovan of UBS AG: Higher-frequency data showed consumers spending more, but continuing to save more as well. The spending data was helped by restaurant spending — the international spillover from service sector spending is not zero, but certainly less than spending on goods.

A strong China is not driving a global rally on anything like the scale of the Chinese-driven boom in emerging markets and commodities between 2003 and 2007. What's interesting for equity investors is that the big up-side surprise in the economy over the last six months hasn't been matched, as yet, by a commensurate increase in earnings expectations for Chinese companies. That, according to Capital Economics of London who provided the following chart, provides good reason to believe that Chinese stocks offer good value:  China's relative performance also seems oddly ambivalent after such a positive economic surprise. If we look at the the MSCI China Index relative to the MSCI index for the rest of the emerging markets, there was a pronounced bounce once Covid-Zero restrictions began to be relaxed in late October, but that had petered out by the end of the year. China's stock market has merely traded in line with the rest of the developing world so far this year, even as the economy exceeds expectations: Why is this? In part, it can be attributed to the way the recovery has been obtained. It may well be a great outcome for the Chinese people in the longer term, but it's not conducive to a stock-market boom. Rory Green of TS Lombard cautions that the Chinese emphasis on consumption hasn't been backed by the same kind of massive stimulus handouts seen in much of the West. That limits how big a rebound the economy can enjoy: This recovery will be weaker than that experienced in the West and peer East Asian nations. China was one of the few countries not to engage in consumption stimulus and/or policies aimed at boosting the equity and property markets. In fact, the opposite occurred via the tech and real estate crackdown. This means that what savings have accrued belong overwhelmingly to the wealthy, and even these savings are offset by weak positive to outright negative wealth effects from falling property prices.

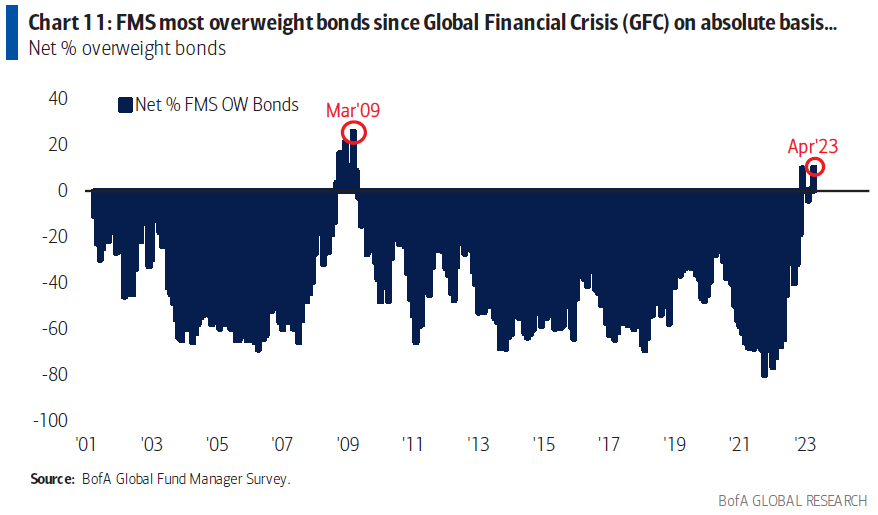

The other problem, of course, is politics. With China in the midst of negotiations with a number of world leaders and its battle with the US over access to technology growing uglier, there is a limit to western investors' willingness to take a chance. Political risks are hard to judge, and money managers as a general rule aren't paid to try to manage them. Tony Roth, chief investment officer at Wilmington Trust, says that China "is still investible," but "the degree of a portfolio that can be helpfully invested in China is shrinking every day due to the geopolitical conflict that exists and the lack of rule of law in China." Both the Chinese government, which reserves the right to clamp down on the private sector if it wants to, and the volatile US political environment, which might easily lead to limits on investment into China, will inhibit allocations. More risk should, of course, drive greater potential returns, but some would prefer to avoid that risk. The bottom line is that China is making progress to what should be a much more stable growth model, and that buoys everyone else while reducing risk. The question now is whether the big political discount that's being applied to Chinese assets is excessive. Just when investors thought things couldn't get any worse after 2022 gave them the war in Ukraine, an aggressive Federal Reserve and surging inflation, banking turmoil hit financial markets last month. That led to the spectacular collapse of several regional lenders, and prompted concerns about a looming credit crunch. Against this backdrop, global fund managers were polled by Bank of America Corp. earlier this month, and said a credit squeeze (and consequent global recession) was the biggest tail risk to markets. This fear literally came out of nowhere. It's worth noting that it wasn't even mentioned as a risk last month, as evidenced by the lack of a light blue horizontal bar in the top line: The monthly survey canvassed nearly 300 participants with roughly $700 billion in assets under management from April 6-13, and captured sentiment for the first time after the March mini-banking crisis. It highlighted how investors still worry about high inflation, despite concerns about a financial disaster which would normally be thought of as deflationary. Investors now face a wall of worry, particularly in equities. This was the most bearish survey so far this year, and many said they had trimmed their stock allocation — down 2 percentage points month-on-month to 29% — as sentiment dipped and growth expectations worsened to levels not seen since December 2022. In fact, a net 63% of participants now expect a weaker economy. The chart that follows is the BofA composite measure of optimism, and suggests sentiment is fully as bad as during the worst of the Global Financial Crisis: That sounds a tad extreme, but at least it benefits bonds. Fears of a credit crunch drove fixed-income allocation up 9 percentage points month-on-month so that investors are now a net 10% overweight. That's the largest overweight since March 2009:  The comparisons to the desperate days of 2008 continue. Investors are underweight equities relative to bonds to an extent not seen since the GFC. That's quite startling — for all the problems at present, the risk of absolute disaster seems nowhere near as close as it did then. What's interesting is that the S&P 500 has soared about 8% year-to-date (while other major indexes around the world have done better), notching weekly gains for the past five out of seven weeks. Someone somewhere continues to buy stocks, even while expressing dire negativity about them. That the S&P 500 keeps climbing as other asset classes fall ahead of the most-anticipated recession has prompted Wall Street investors to question the market's resilience. Adding to the confusion is the relatively calm VIX, which measures volatility or "fear" from investors' positioning on the options market. It is currently at its lowest in 18 months. So why are equities rallying? Roth of Wilmington Trust said it's likely because of a belief that the banks' problems will stop the Fed from hiking rates aggressively (although he is still in the camp that thinks there won't be cuts this year.) A recession will likely unfold , he added, which would negatively impact earnings: Something has to give because the consensus economic forecast is for a recession to start in the second half of this year and the consensus equity analysts are telling us that we're going to get positive earnings. They both can't be right. If we have a recession, we're going to get further deterioration in earnings. So do you believe the equity analysts or do you believe the consensus economic outlook?

Perhaps contributing to the resilience of stocks is that they were positioned for something even worse at the beginning of the year. That turns every little piece of "good news," in the form of better-than-forecast data, into a reason to cheer and buy stocks, said Lori Calvasina, head of US equity strategy at RBC Capital Markets. For a technical analysis on equities' grind higher, look to Ralph Davidson, chief equity strategist and portfolio manager at BTG Pactual US Capital. The uptrend, he wrote, has been due to mispositioning, money flows and sentiment — technical reasons rather than fundamental. Like the majority, his current overall equity allocation is underweight in all regions. But if investors were too underweight in equities entering the year, the BofA survey suggests that the problem is worsening: At the center of all of this is the turmoil in the financial sector. It would be interesting to see how much fund managers' answers would change if they were shown the first-quarter results from the large commercial banks to have reported so far, which have generally been very good. The degree of concern about financials looks startling: Investors' allocation to banks and insurance fell 12 percentage points and 13 percentage points, respectively, to their lowest since the worst of the pandemic in May 2020: Normally, problems for the banks betoken problems for everyone — hence the deep bearishness about the economy. So, how to explain the co-existence of near-2008 level angst over the banking sector with a calm and rising stock market? Paul O'Connor, head of the UK-based multi-asset team at Janus Henderson, said the mini crisis could be perceived as "confirmation" that interest-rate increases are beginning to bite: Tighter credit conditions is one of the key channels through which monetary policy works, and is not necessarily a sign that something has gone wrong. Rising interest rates and slowing economic growth dampens confidence in the banking and credit sectors, leading to tighter financial conditions which ultimately slow growth further.

It might work out that way, although expectations for rate hikes have begun to move back upward in the last few days. Perhaps the strongest lesson from the sharp drop in sentiment that the bank failures have induced is that the optimists, to quote Yeats, lack all conviction, while the bears are full of passionate intensity. Sentiment can change so swiftly because nobody is really sure what is going on. — Isabelle Lee As I'm in the UK, a British binge-watching recommendation. Strike, a TV adaptation of the detective novels that J.K. Rowling has written under the pen name Robert Galbraith, is superb and absorbing television, centered around the dynamic between the partnership of Cormoran Strike, a military veteran who lost a leg in Afghanistan and is now a private eye, and Robin Ellacott who joins his firm as a temporary secretary and soon becomes another detective. Their "will they won't they" relationship is mighty believable, and is always there in the background while the dark plots unfold. I gather it's on Hulu and HBO Max in the US, and I strongly recommend it. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment