| The credit market is trying to tell us something. But what, exactly? Look at it almost any way, and credit is available at rates that imply no particular risk of default, and very little risk of recession. In both the euro zone and the US, high-yield bonds are looking misnamed. After a brief and sharp rise last year, their spreads over equivalent five-year government bonds are right back to a level that suggests all is quiet: The pattern continues in investment-grade credit. And if we compare it with cash in the form of the yield on six-month Treasury bills, the reward for risking an investment in corporate credit is historically low. The spread is less than 1%, and at one point dipped below the low set in the spring of 2007, just as the Global Financial Crisis was about to break out: This flies in the face of other important indicators. The Federal Reserve's survey of senior lending officers measures whether banks are tightening or loosening their lending standards, and at present shows a sharp tightening. As demonstrated in the chart by Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist at Societe Generale SA, tighter bank standards generally imply higher credit spreads, at least for junk bonds. But not now: In Europe, Apollo Group's chief economist Torsten Slok shows that bankruptcies in the sectors most affected by the pandemic, such as transportation and accommodation, have started to rise sharply. Overall, bankruptcies are still roughly in line with the trend since 2015, but these numbers still make it hard to explain a narrowing in high-yield spreads over the last few months: Meanwhile, the stock market seems also to be comfortable with credit risks. Bloomberg's Factors To Watch function (FTW <GO> on the terminal) includes a measure of a stock's returns that can be attributed to its degree of leverage. Understandably, the leverage factor tanked during the first Covid lockdown of March 2020, and rebounded in full by the end of the year. Despite sharply rising interest rates, at a pace very few people had predicted, the FTW measure suggests that leverage has been close to a non-issue for the last two years: Ranking stocks according to their distance from default, Lapthorne at SocGen shows that shares of companies with the weakest balance sheets have outperformed of late. This suggests minimal fear of defaults: All of this looks very strange. Even with cash offering a guaranteed return over six months that is close to the yield of corporate credit, there doesn't yet appear to be any great concern. The parallels with the GFC, which began in 2007 as credit markets that had long been absurdly overvaluing corporate and mortgage-backed credit began to crack, are obvious. The fact that corporate credit is now trading at a spread over six-month Treasury bills only previously seen in the spring of 2007 is disquieting to say the least. But it's also important to note that there's a lack of data; if we had a bunch of crises on the scale of that one to look at, we might have a better ability to work out whether the current credit market is dangerously relaxed. To quote SocGen's Lapthorne: With interest rates much higher and profits falling, you'd think investors would be more concerned about credit risk. While updating our models, we reached a familiar conclusion: markets seem to be largely ignoring the consequences of much higher interest rates and apparently rapidly evaporating excess profitability.

So the credit market could be telling us that we are back in the realm of irrational equanimity, brewing perfect conditions for a crisis. But there's another way to look at it, which is that the credit market might just conceivably have it right. Memories of the GFC are still fresh. People keep making the same mistakes, but it's rare to repeat a mistake quite this big quite this quickly. And while the credit market looks alarmingly tight given the environment of rising rates and fears of recession, there are other ways in which this is very different from 2007. The critical one is that consumers' balance sheets are in much better shape, in part thanks to learning the lessons of the GFC, and in part because households received so much government largesse to tide them through the pandemic. Chris Harvey, equity strategist at Wells Fargo Inc., suggests that we should trust the credit market as saying that the underlying economy is "muddling along," rather than in any kind of crisis: When we talk about the consumer, what we're arguing about today is how much of the excess savings they've spent and how soon they will run through that excess. That is a very different conversation than should we give the keys back to the bank for our house or our car. Those were the conversations that were happening in 07-08. So we think it's more resilient because the underlying fundamentals and earnings are resilient. Last year's bear market was driven by cost of capital, and we don't think there's a ton of upside, but the credit markets are telling you that the underlying economy's okay. It's not in high distress, and the systemic risk is not comparable to the early 2000s or 07-08.

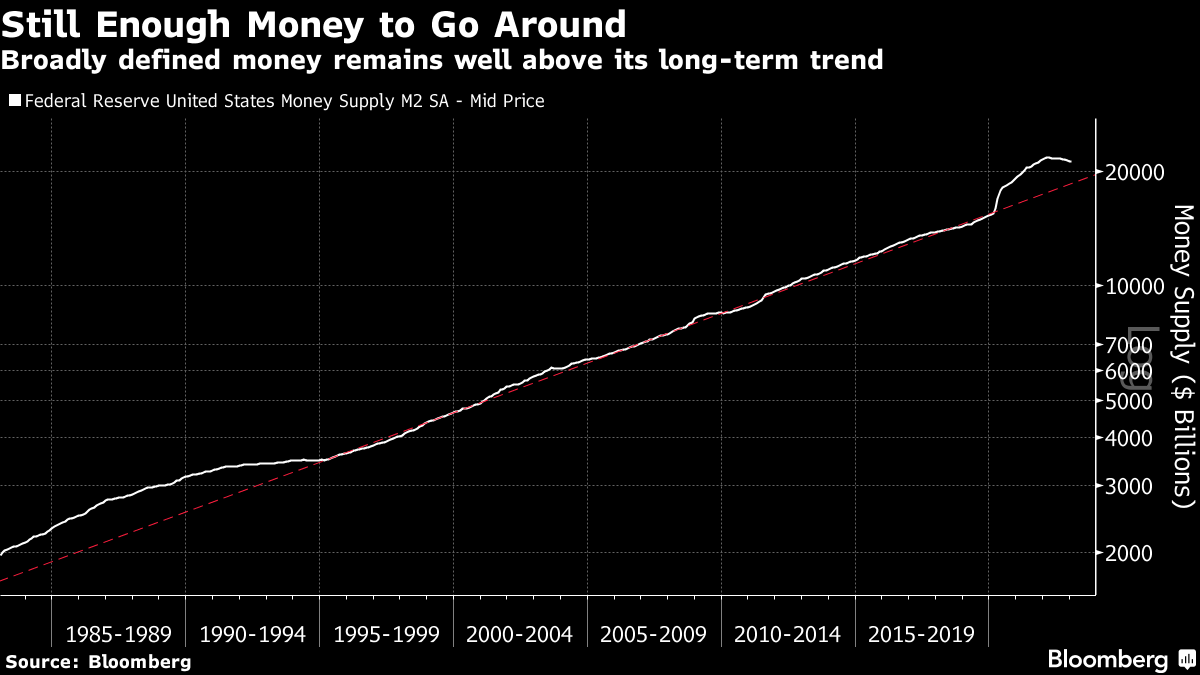

It's hard to deny that the massive expansion in the money supply changes things. It's arguably the key factor in causing inflation to ignite again; but it also helps to explain why there is so little financial distress. As the following chart produced on the terminal shows, money supply is still comfortably greater than would be expected given its very consistent historic growth trend:  On top of this, households across the planet attempted to clean up their balance sheets after the crisis, with some considerable success. Counterintuitively, the countries worst affected by the GFC tend now to have the cleanest household credit, because it was so hard for people to borrow in crisis conditions. If you don't have a mortgage, you're not going to default on it. George Saravelos, foreign-exchange strategist at Deutsche Bank AG in London, illustrates this with a dramatic divergence between Greece (hit worse by the crisis and its euro-zone aftershock than any other country) and Sweden (relatively mildly affect). Swedish house prices are tumbling, while in Greece they're still rising. That's probably because the Greeks started with far less private sector debt; higher rates were far less painful for them: Saravelos moves from this to make a point that underlines the importance of private debt in this cycle: How has Italy managed to survive the biggest energy crisis in Europe's history, the fastest ECB tightening cycle on record and the departure of Draghi, all in less than a year? The answer is simple: Italy and Greece have the lowest private sector debt in the developed world; Sweden has the highest. It was near impossible to convince investors last year that the ECB could hike rates above 3% without a European crisis. It is similarly an uphill struggle to argue that the ECB could hike rates to 4% this year – even though European unemployment is at record lows, equities and core CPI are at record highs. But, investors focusing on public sector debt risk looking at the wrong variable. Sweden's government debt is only 40% of GDP yet its economy is the weakest in Europe; Greek government debt is the highest in Europe yet its economy is the strongest. Private sector debt is the key variable to watch in this cycle. ECB tightening is having a small impact in the European periphery. Why? Simply put, very few Italians or Greeks have a mortgage.

While households and corporations can still service their debts as easily as they can at present, there is no risk of a repetition of the GFC. The problem is that it might not be possible to beat inflation without the kind of genuine tightening that comes when businesses are driven to the wall. For a revealing insight on this, listen to this podcast in which my colleague Vildana Hajric asked Alan Blinder, now a professor at Princeton, about an anecdote he tells about Paul Volcker. As a young academic, he once asked the man now lauded as the slayer of inflation just how monetary policy could bring inflation down. Volcker's reply: through bankruptcies. Tighter rates, in his view, worked by pushing some businesses to the wall and squeezing the life out of inflationary pressures. Assuming Volcker was right about this, then perhaps the credit market does have a message for us. Rates will have to rise further, until they force defaults (and bring down corporate profits), before inflation can be beaten. — Reporting by Isabelle Lee Happy St Piran's Day. If you're not aware, St Piran was an Irish monk who brought Christianity to Cornwall and became Cornwall's patron saint. Legend has it that he crossed the Irish Sea floating on a millstone, and then taught the Cornish how to mine tin. His name is embedded deep in the culture of Cornwall, where I was lucky to spend much of my childhood, not least in the many musical place names, such as Perranzabuloe, or Perranarworthal, or Perranuthnoe. But Piran seems to be gaining an even greater hold on the culture as the years go by. A revival of the Cornish language that gave us those great place names is under way more than a century after the last person to speak it as a mother tongue passed away. And St Piran's Day was celebrated throughout the Duchy. It's even celebrated in Mexico. When tin was discovered there, miners from Cornwall crossed the Atlantic to show them how to extract it from the land. They brought with them soccer (Mexico's oldest team, from the mining city of Pachuca, is nicknamed Los Tuzos, or The Moles, in honor of the miners), and the Cornish pastie, which in the state of Hidalgo is known as a "paste" and comes with all kinds of spices or tropical fruit as a filling. So, try listening to the Cornish national anthem Trelawny, in English, or Cornish. Or the great celebration of Richard Trevithick's steam engine, Going Up Camborne Hill. You don't have to be drunk to sing it but it helps. For slightly greater music, try the Cornish baritone Ben Luxon singing Sea Fever and his compatriot Alan Opie singing a very famous aria from The Barber of Seville. Have a good week everyone. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment