| Ahead of the testimony of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell before Congress, the widespread expectation was that he would remain hawkish and lay the groundwork for a higher terminal rate. That he would defend his policy of staying in an extended period in restrictive territory and largely stick to his script. He fulfilled his side of the deal and did all of this. And yet many were still unprepared for just how hawkish the Fed boss was. This was the key line in his prepared testimony: The latest economic data have come in stronger than expected, which suggests that the ultimate level of interest rates is likely to be higher than previously anticipated. If the totality of the data were to indicate that faster tightening is warranted, we would be prepared to increase the pace of rate hikes.

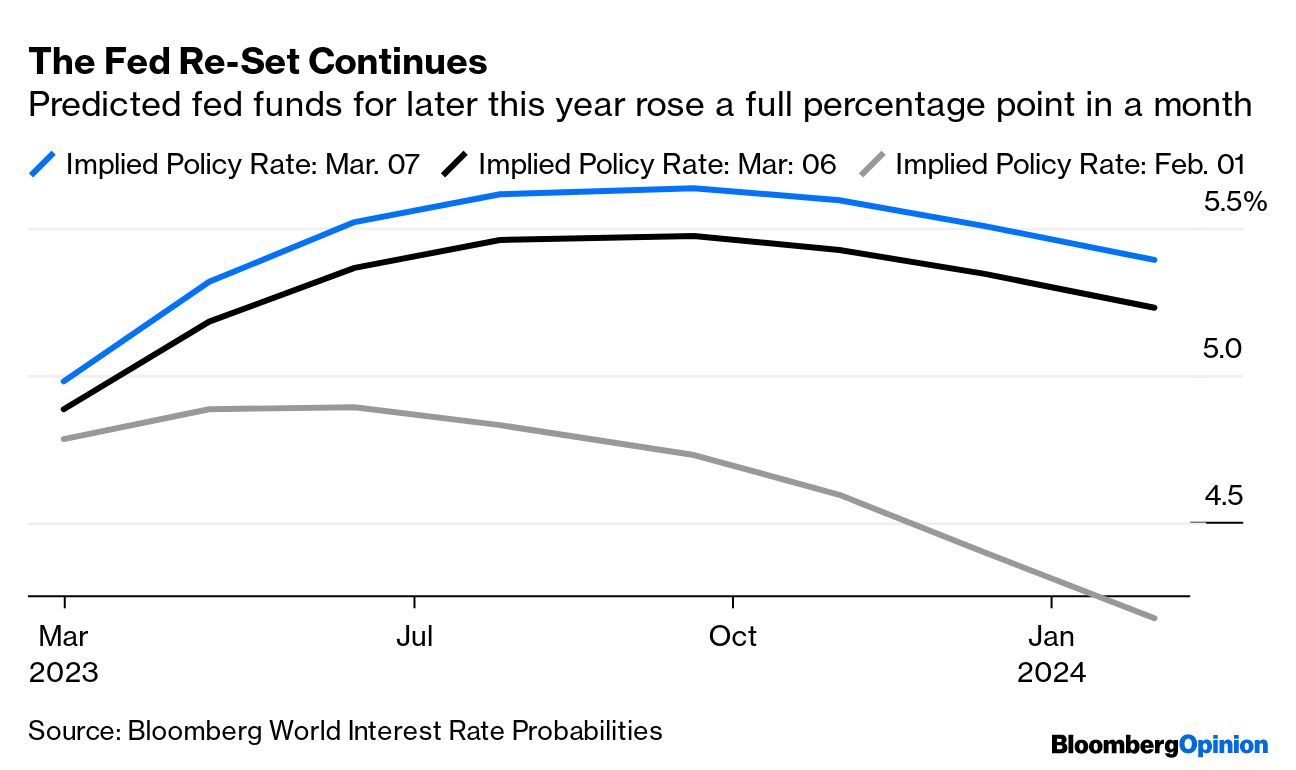

So, he was explicit that he might lift the Fed's benchmark lending rate by a half percentage point at the March 22 meeting, pending major economic data, was all investors needed to hear. Treasuries sank to fresh lows with swaps bets shifting to show that traders now expect the Fed to be more likely to announce a half-point hike rather than a quarter point. This raises the key borrowing costs by 107 basis points over the next four meetings to a peak of about 5.6%. Using the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function (WIRP on the terminal) for deriving implicit predicted fed funds rates after each meeting from futures prices, we can see that the entire predicted curve was yanked up. The contrast with the predicted course after Powell's last big press conference on Feb. 1, when several rate cuts were baked in, is quite remarkable:  Perhaps it's safe to interpret this as an abandonment of the belief, still in circulation on Feb. 1, that it was possible to bring inflation down to target without creating major job losses or a recession. That looks harder now. In a disquieting sign that has long functioned as a recession predictor, the spread between the two- and 10-year Treasury yields widened to as much as 104 basis points, the deepest inversion since 1981. Thirty-year yields are 111 basis points below two-year rates, a record gap between the two: For another landmark, the two-year Treasury note's yield increased to 5% for the first time since July 2007. It has jumped from a 2023 low of 4.03% in early February as traders adopted higher forecasts for the peak Fed policy rate: Powell's prepared introductory remarks had an instant impact on the stock market. A few attempts to recover during the question-and-answer session weren't successful, and the S&P 500 Index closed down more than 1%, back below 4,000: In Europe, nearing the end of the trading day when the prepared remarks were published, his words turned a mediocre day into a bad one: This was a big deal, and — as unfortunately flagged in Points of Return yesterday — people generally hadn't expected it to be. The timing of Powell's appearance seemed to make it difficult for him to generate any news, as there are still several major data releases before this month's Federal Open Market Committee meeting. These include non-farm payrolls and consumer-price inflation numbers for February. If they were to have as big an impact on the outlook as the last data points in those series, they could yet swamp what Powell has just said to Congress. So why was he so outspoken? In essence, it was a reality check. For Seema Shah, chief global strategist at Principal Asset Management, the testimony was an admission that the FOMC fell for the "old seasonality trick," as it confronted relatively soft data for December: They didn't follow their own advice about not being swayed by one month's worth of data and Powell has now essentially had to do a U-turn as the evidence of strong price pressures has piled up. Fortunately, Powell's message this time is clear: the Fed does not yet have the inflation space to consider pausing rate hikes and it likely will not have the inflation space to consider cutting rates later this year.

Steven Blitz of TS Lombard agreed, describing his words as a "tacit admission" that February's downshift in hikes had been a mistake. The Fed did this because the peak rate appeared to be close but: "They are, in fact, no closer to understanding where the peak rate resides than they were a few months back, because they have no idea where disinflation will settle without a recession." Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research raked through the Powell press conference from the beginning of last month to show that at the time he appeared to buy the case for a gradual "disinflation:" The word 'disinflation' was uttered 11 times at Powell's press conference on February 1. He was the only one who mentioned the word at his presser. He repeatedly acknowledged that inflation was moderating but still had a ways to go before reaching the Fed's 2.0% target. Nevertheless, Powell sounded much less hawkish than during his previous presser on December 14, 2022, when the word was mentioned only twice, both times by reporters. In his congressional testimony today, Powell mentioned the word just once in his short prepared remarks with a hawkish spin

Whether Powell did a bad job of communicating at the time, or whether a close analysis of his comments show that he really was more dovish a month ago, Yardeni suggests that these comments were genuinely different. There is at least one good explanation for this, which is that January's data points were not only hot but almost all hotter than expected. That leaves profound questions which hinge on the next data releases, rather than Powell's opinions. Here's Zhiwei Ren, portfolio manager at Penn Mutual Asset Management, on risks that might pose: The question that I have now is: Is the economy reaccelerating? Basically we saw some weakness in November and December, but now it looks like growth is picking up. If that continues in February then that's a real risk to the Fed because if the economy is able to reaccelerate in January and February, that means even though they have higher interest rates by March — that's still not restrictive enough to stop the momentum in the economy — and that means the fed funds rate can go much higher than we thought. Maybe go to 6% and stay there for a while. So that's the risk to the market at this point.

Another talking point that caught the attention of investors is Powell's insistence on the Fed's inflation target. He admitted that "the process of getting inflation back down to 2% has a long way to go and is likely to be bumpy." It's back to the old debate of whether the Fed's inflation target is at all attainable. To Solomon Tadesse of Société Générale, it isn't. "Everyone is basically assuming that it'll go down to that 2%, but really 2% is unattainable," he said, adding that the target needs to be revised higher. There is one caveat: "The Fed cannot do it now because its credibility is in question," he said. "It has to first tighten further to establish credibility.'' But the discussion to reduce its target should come by the end of the year. For its next meeting, the biggest shift could be in the "dot plot" — in which each governor's projection for where the fed funds rate will move over time is shown as a dot. They are due to be updated for the first time since December. As this chart from NatWest Markets shows, the dots shifted upward between September and December: After Tuesday, the chance that the median prediction for the end of this year will move upward again looks very high. It also might make sense for the committee's predictions in 2024 and 2025, which could scarcely be more scattered at present, to begin to converge toward the high end of current predictions. And what might be most interesting would be a shift in the longer-run dots to accept that the fed funds rate will not drop all the way back to 2%. — Reporting by Isabelle Lee Outside the innermost realms of financial geekery, there are few market terms that cause more consternation and confusion than the yield curve. In particular, while everyone with an interest in markets knows that an inverted yield curve is a recession signal, big questions remain. To start with: Why? And does it matter just how deep the inversion gets? On a day that has seen only the fourth full-percentage point inversion in a century, it's worth asking. In general, an inversion acts as an on-off switch, rather than as a dimmer. If 10-year yields drop further below two-year yields, that means more investors are convinced that a recession and cut in rates is coming — not that the slowdown will be even worse. That said, a 100-basis-point inversion does look like a foolproof augury of really bad times. Taking the gap between the three-month and 10-year yields as a yardstick, analysis by Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research in London, shows that this is only the fourth 100 basis points inversion since 1920. Prior such inversions came in the spring of 1929 and the summer of 1973, shortly before two of the greatest financial implosions in history, and then again in 1980 as Paul Volcker forced a recession in his bid to vanquish inflation. All of these were bad times, but the Fed reaction was a crucial variable — an over-tight Fed led to a decade of depression and deflation after 1929, while the dovish Fed of the 1970s allowed stagflation to take hold. The Volcker intervention, involving a brutal but relatively brief recession followed by a prolonged recovery, is the one that Powell is trying to emulate. Bespoke Investment offers this detailed analysis of the Volcker-era inversion. Counterintuitively (like most everything else that has to do with the bond market), stocks didn't do so badly: After the 2s10s curve first inverted in October 1979, the economy peaked at the end of January 1980. Despite the fact that the economy went into a tailspin, in the year that followed that first reading where the curve was inverted by more than 100 bps, the stock market was rather strong. While it was far from a smooth ride, over the course of the next year, the S&P 500 rallied 22.9%, the Nasdaq was up 36.0%, and the Russell 2000 was up over 40%.

Here is how it would have worked out if you'd bought the S&P 500 the last time the curve became 100 basis points inverted: How much should we weigh on this? Not much. As Bespoke admits, a sample size of one is hardly enough of a track record to draw any conclusions. Then there's the very important issue of valuation: Back then, the S&P 500 was trading for just 7.3 times trailing earnings. Today, the S&P 500 trades at a multiple that's two-and-a-half times that level. While valuations today are much higher than they were then, interest rates are still a lot lower. Back in October 1979, the yield on the 10-year was at 10% which also happens to be two-and-a-half times the current 10-year yield.

That 20% gain over 12 months that included the Iranian hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and other horrors, shows what might still be possible from today's straitened position. But it's the kind of bounce that is much easier to achieve when markets are massively oversold. That's nothing like now. There's another way to interpret the strength of a yield-curve signal, which is to look at its width rather than its depth. Yield curves stretch out for 30 years; there are many different pairs of points that can be compared, and the more are inverted, the more confident we can be that a recession is coming. As the following chart from Absolute Strategy shows, the yield curve is now inverted along almost all of its length. Historically, that is indeed a reason to take its recession signal that much more seriously: One final question: Does the yield curve really matter? Obviously, as a general rule, long-term rates should be higher to compensate for the greater risk attached to lending further into the future, but an inversion isn't directly causal of a recession — it merely shows that bond investors are positioned for one. There is one big exception to this logic, however, in the banking sector. Traditionally, banks make their money from the difference between borrowing short-term cheaply (through deposits and current accounts), and then lending long-term at a higher rate (through mortgages, business loans and so on). An inverted yield curve scuppers this business model, and ultimately deters banks from lending. This is why inversions can't persist for too long. Financial services groups are less dependent on the profits from interest than they used to be, and have looked for ways to make more money from fees, which are more stable. But an inverted curve is still a problem, particularly for regional banks whose business remains dominated by lending. And indeed their performance has lagged the market painfully since rates began to move a year ago. All their outperformance since successful vaccine trials convinced investors that growth was back has been canceled out: It's worth keeping a very close eye on the banking sector. So far, the signs of a financial crisis as a result of the Fed's tightening campaign have been minimal. Any hint that investors think the current financial conditions will rock their stability could change that. I have a multimedia long read for you. Someone somewhere had the idea that it would be great to do a taxonomy (or "claxonomy") of all the car horns you can hear in Mexico City, and what they mean. It brings all kinds of good memories back for me, and it's a great read and listen even if you've never yet been to La Capital. Here it is. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment