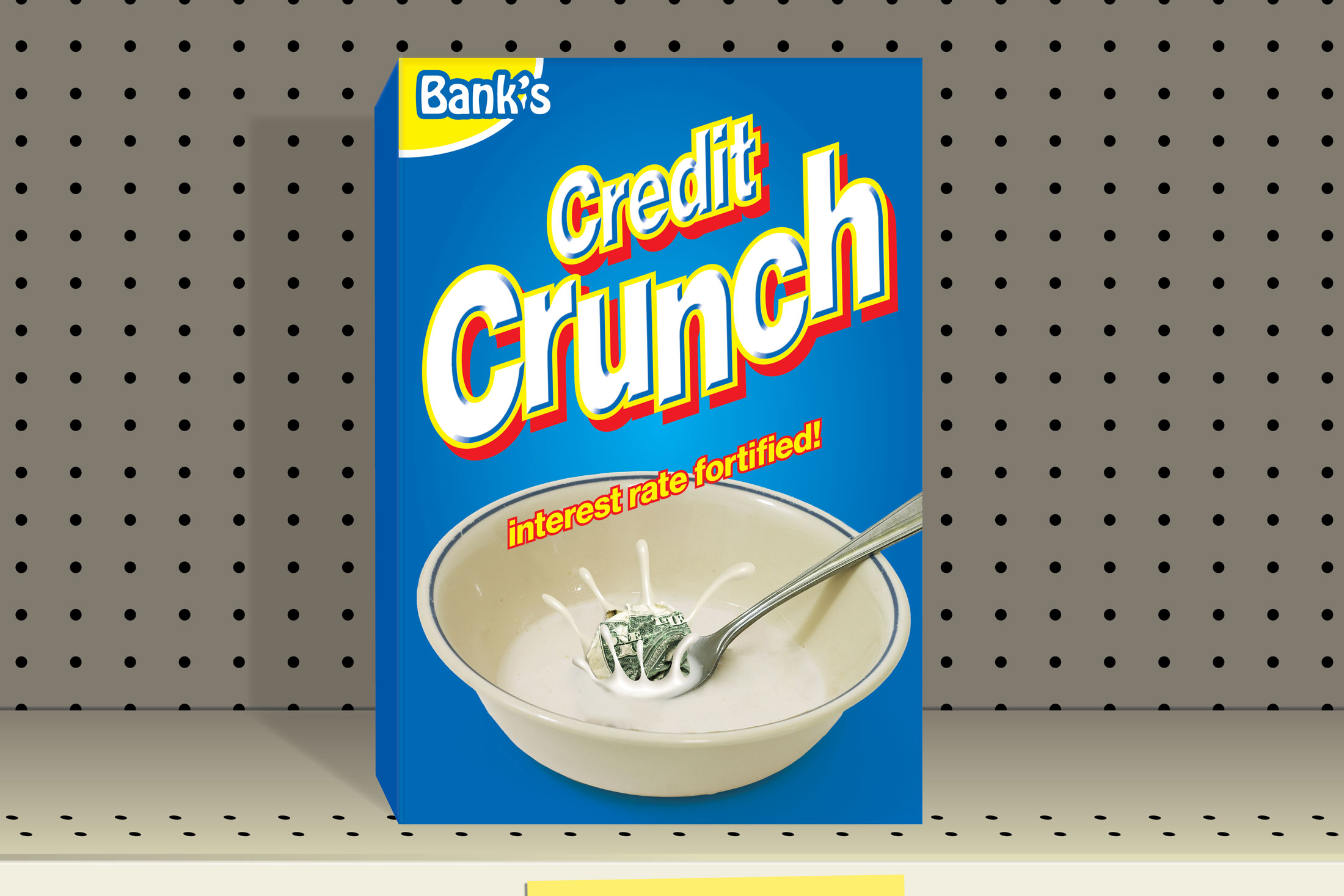

| Welcome to Bw Daily, the Bloomberg Businessweek newsletter, where we'll bring you interesting voices, great reporting and the magazine's usual charm every weekday. Let us know what you think by emailing our editor here! If this has been forwarded to you, click here to sign up. And here it is … The biggest banking scare since the 2008 financial crisis will ricochet through the economy for months as households and businesses find it harder to gain access to credit. That's the scenario facing the US after the collapse of three regional lenders, and a giant global one, over an 11-day span, according to several economists. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Neel Kashkari, in a March 26 interview on CBS's Face the Nation, said the turmoil "definitely brings us closer" to a recession and noted that officials are closely watching for signs of a widespread credit crunch.  Photo illustration: 731; Photos: Alamy, Dreamtime The concern is that banks will curb lending in response to increased regulatory scrutiny, erosion in deposits or a drop in the value of their equity, at a time when the Fed is already pushing ahead with the most aggressive cycle of interest-rate hikes in 40 years. The Fed's benchmark interest rate is at its highest level since 2007, the eve of the financial crisis. Small and medium-size banks in particular are expected to tighten lending standards, which will hurt households, property prices and the kind of midsize companies that make up the backbone of the economy. UBS Group AG estimates smaller and regional banks hold about 39% of commercial real estate debt. Although it will take months before solid trends emerge from available data on bank lending, history is littered with examples of tighter credit conditions leading to higher unemployment and slower economic activity. In an analysis of three academic studies, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. concluded the recent turmoil may lead to a 2% to 5% reduction in lending in the US. Moody's Analytics Chief Economist Mark Zandi reckons tighter credit will lower growth over the rest of this year by 0.3 percentage point, while Michael Feroli, chief US economist for JPMorgan Chase & Co., says the toll could be a half to a full percentage point over this year and next. JPMorgan Chief Market Strategist Marko Kolanovic says the banking stress has increased the chances of a "Minsky moment"—a sudden crash of markets and economies that have grown accustomed to cheap money. At one point in March, the Bloomberg US Financial Conditions Index tightened to levels not seen since May 2020. A more benign take is that market volatility will dissipate as investors realize this isn't a replay of 2008. Banks are well-capitalized, bad loan volumes appear contained and regulators have responded early, says Rob Subbaraman, chief economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. "Bank loan growth is very likely to slow, but I think it's a bit too early to conclude that it is going to collapse," he says. Indeed, Goldman's analysis found that failures tend to spread only if bank fundamentals are weak, banks are highly interdependent or an initial failure exposes systemic risks. Furthermore, a rapid tightening is exactly what policymakers have been seeking to slow inflation. Torsten Slok, Apollo Global Management's chief economist, estimates the banking shock will raise the cost of borrowing just as much as a 1.5-percentage-point increase in the Fed's target interest rate. In a report published on March 27, Jan Hatzius, Goldman's chief economist, said his team's baseline assumption is that reduced credit availability will prove to be "a headwind that helps the Fed keep growth below potential" rather than "a hurricane that pushes the economy into recession." There are signs that lending was tightening before the banking drama and will only get tighter. Bloomberg's bankruptcy tracker shows 52 large company filings in the year through March 27, the most in a comparable period since 2009. Even if banks are still willing to lend, consumers may not want to borrow. A Citigroup Inc. analysis of credit card data that covered the period when banks were dominating the news showed the biggest decline in consumer spending since the pandemic. In a note published on March 23, economists and analysts at the Institute of International Finance pointed out that the US economy isn't nearly as dependent as others on bank lending because US capital markets are broad and diversified, and therefore "a recession is far from a foregone conclusion." Nonetheless, the authors noted the lesson from other countries is that variations in what economists call the credit impulse, a measure of changes in the pace of credit growth, is closely associated with ups and downs in economic output. "Policymakers need to take developments in the credit space extremely seriously—which they are—and to be proactive when it comes to keeping credit flowing," they concluded. —Enda Curran, Bloomberg senior economics reporter |

No comments:

Post a Comment