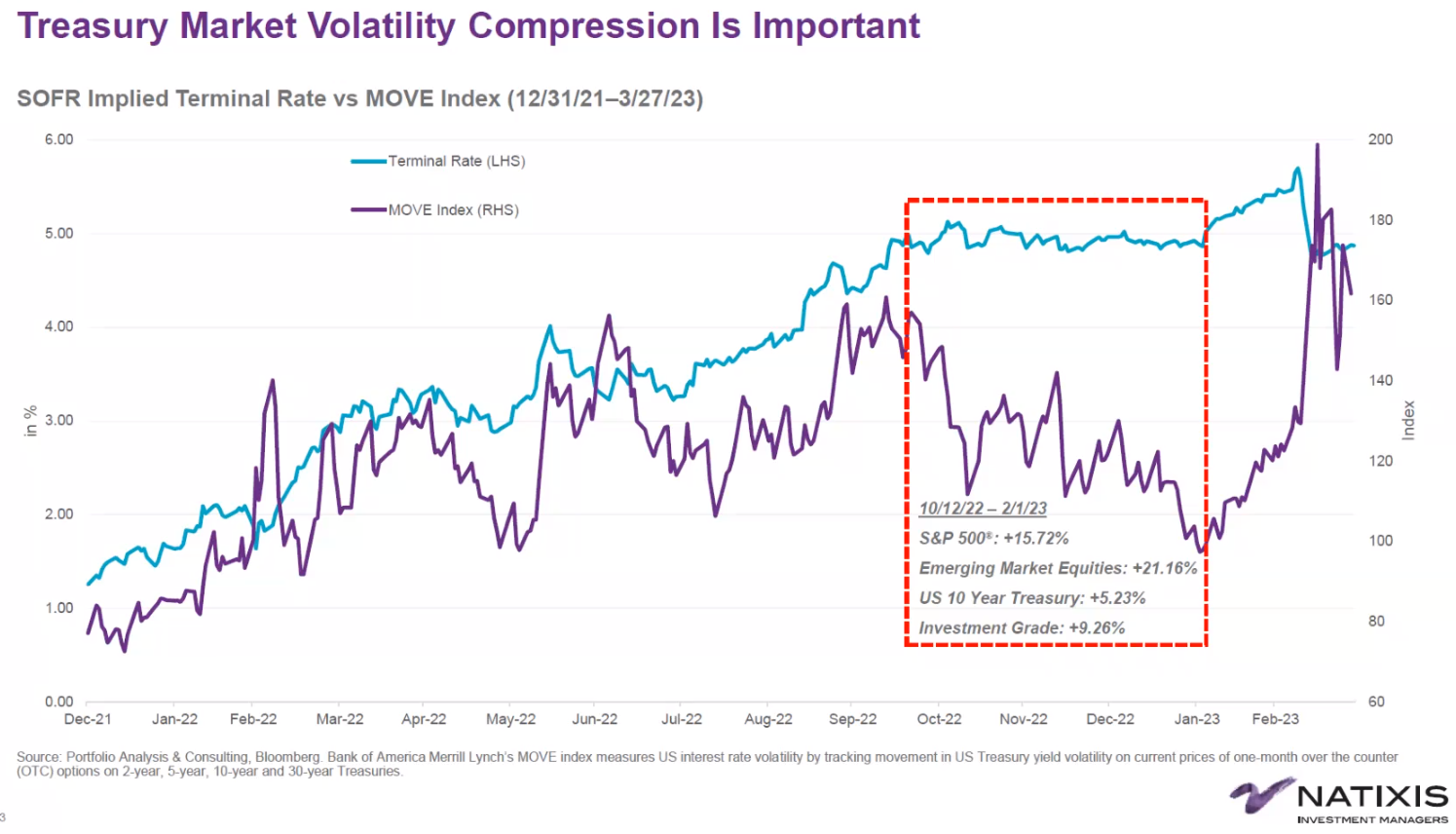

| This month, US capital markets sustained one of their biggest shocks in memory. The hit to bank stocks and the rush into bonds were both fully comparable in their severity to anything outside the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. With banks in upheaval, predictions for monetary policy turned through 180 degrees. Suddenly, investors assumed that rate cuts were coming imminently to deal with an incipient recession. I put all of this in writing just to emphasize how strange it is that March is still not quite over, and yet the Nasdaq-100 is at its highest since last August. Stock markets across the globe all appear to be in a barely interrupted upward trend still. How to explain? It's best to break this into parts. First, why was the shock earlier this month quite so severe? And secondly, how have investors managed to calm down so quickly? It looks to me as though both were rather exaggerated. The extremity of the bond market spasm shows up most clearly from the MOVE index, a widely quoted gauge of volatility. It rose far higher as banks failed than it had even during the worst of March 2020, when the market appeared to cease functioning: That spike owed much to the long torpor that preceded it, and to the fact that the problems for banks came almost completely out of left field. Lehman Brothers' financial health had been a major topic of discussion on the markets for many months by the time it collapsed; Silicon Valley Bank was closed by regulators within hours of its problems first making headlines. Peter van Dooijeweert, head of multi-asset solutions at Man Solutions, offers this assessment: I don't think any of us saw the specific banks in question coming. Maybe a few people did, but by and large I don't think people saw it coming. So I think that reaction wasn't insane. The GFC was a long time ago. So our tendency is going to be to first overreact. The bond market was increasingly pricing inflation, and overnight with the SVB bank failure had to start pricing a deflationary shock due to credit creation. So that tremendous move in the MOVE index is incredibly consistent with an absolute overnight rerating. It's a complete shock to the system. The equity market seems to have dealt with it better, if we look at the top line and VIX.

Everyone knew that there was a risk that bonds could be thrown for a loop at any time — it's an issue that's been anxiously discussed for a decade. A second issue concerns expectations for the Federal Reserve. Calling the fed funds rate at each meeting doesn't matter that much to bond volatility, while it's widely acknowledged that nobody can offer a precise forecast of overnight rates a decade into the future. What does seem to matter, however, is the terminal rate — the level at which the fed funds rate will stop escalating in this cycle. The following chart from Natixis Investment Managers shows that volatility rose as estimates for the terminal rate also ascended in the first nine months of last year. Once terminal estimates reached a plateau in October, underlying volatility could decline. February's slight pick-up in terminal rate expectations, as macro data came in much stronger than had been expected, was enough to send MOVE sharply higher. And then the rather more drastic cut in rate expectations as SVB failed sent volatility even higher. At present, terminal rate expectations are back roughly to where they were in January, before the turbulence. The MOVE index remains far higher than then, and it will require terminal rate projections to stabilize at this level for volatility to fall. But we begin to see how such volcanic moves in the bond market could happen:  The other reason for the return to calm is a swift reappraisal of the severity of the situation for the banks. There haven't been further runs in the last week, the banks that failed all had extreme concentrations of uninsured depositors, and the immediate action taken by the Fed — allowing banks to borrow using bonds as collateral and assuming they were still trading at par value — seems to have been effective. That tends to strengthen the notion that this has been primarily a liquidity crisis, rather than an issue of underlying solvency. The former is infinitely preferable to the latter. "There are a handful of poorly managed banks that were exposed to the same concentrated depositor base," says Garrett Melson, portfolio strategist at Natixis Investment Managers. "It seems to be fairly limited in part due to the nature of the crisis and in part due to the policy response from the Fed." Meanwhile, there is another reassessment afoot on commercial real estate, a sector that — as we've covered in Points of Return — has created great anxiety. It's not that anyone denies there's a problem. But it might not be as bad as all that. Thomas Tzitzouris of Strategas Research Partners admits to surprise that his model of banking sector fragility suggests rather limited reasons for concern about commercial real estate: Our model shows that REITs are in clear and present danger of entering credit distress, but banks, particularly the 25 publicly traded banks with the highest percent of CRE loans, are not yet generating a warning on our end... For now, banks with the highest CRE exposure as a % of assets are showing generally less risk than other financial sector issuers.

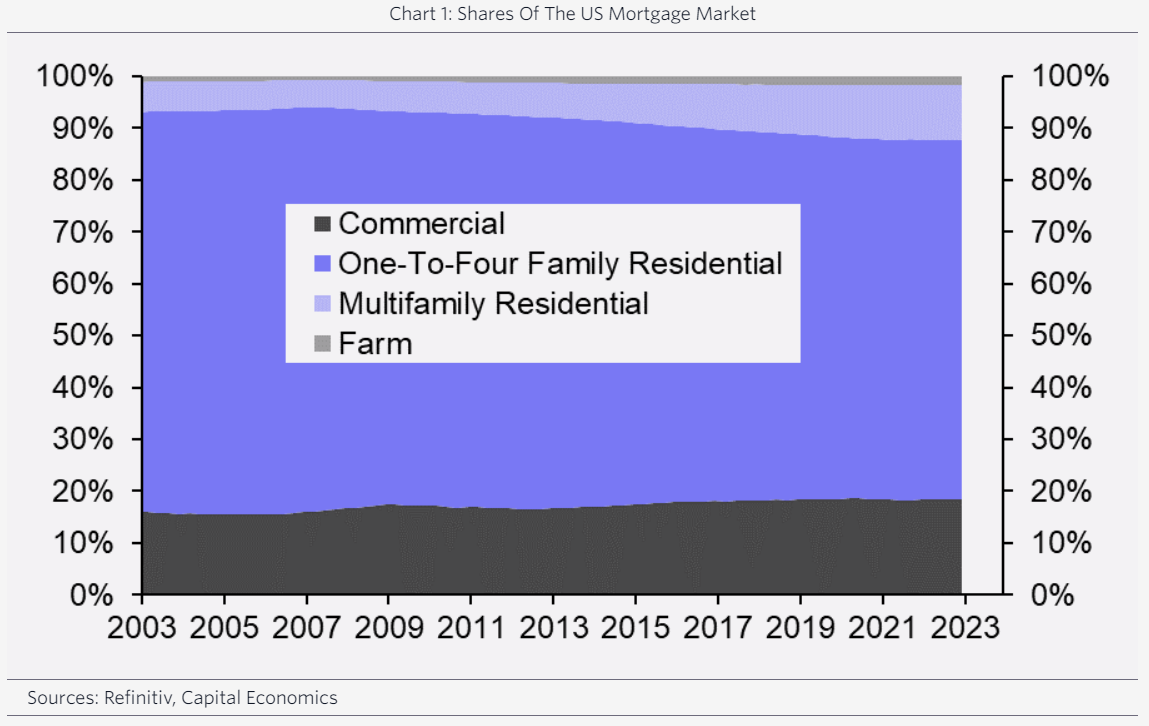

It's true that smaller banks tend to have big exposure to commercial real estate, as Natixis demonstrates here: The other handy point is that small banks are indeed small, and so don't account for a huge chunk of gross domestic product. A range of defaults would certainly harm the economy, and might cause great pain in the communities directly affected, but the banks that have been deemed small enough that they can be allowed to fail should, indeed, be small enough that they don't create too much damage if they do. Their problems give a reason to shade down economic growth projections a bit. They do not, contends Melson of Natixis, give a reason to flip from projecting an expansion and instead predict a deflationary slump: Melson also makes the point that credit standards for CRE have tightened periodically over the last decade, as shown in Fed surveys. That doesn't mean that some bank isn't going to take a serious bath on a development that goes badly wrong, but it does imply that the risks of extreme lazy lending a la 2008, to be followed by a crash, aren't that high: Beyond this, the capacity of commercial real estate to inflict serious damage on the economy is questionable (unlike residential real estate, which we all know can cause a recession). Big skyscrapers and warehouses are eye-catching developments, and there are very good reasons for concern about the post-pandemic future of office buildings. But the amount of money lent against them is dwarfed by the money that goes to finance people's homes. This chart is from Capital Economics Ltd. of London:  That commercial's share of lending has risen so little, from a period when lending to residential was truly extreme, suggests a situation that should be containable. There's also the fact that while foreign banks, particularly in Europe, bought a lot of bad US residential mortgages 15 years ago, they don't appear to be anything like so exposed now to commercial real estate. The following Capital Economics chart shows the total amount of all mortgage-backed and other asset-backed US securities held outside the US. In absolute and relative terms, it's a long way below the disastrous peak from 2007: This doesn't mean that CRE isn't a problem, because it plainly is. It just implies that the issues it causes should be manageable. Most of us take 2008 as our baseline for a banking crisis; at present, there's a risk of something bad, but no imminent reason to fear anything on that scale. John Higgins of Capital Economics comes to the following conclusion: The risk of problems in the US commercial property market directly causing a big headache abroad appears to us to be rather low. That said, it clearly doesn't preclude indirect contagion for other reasons. For a start, problems in commercial markets elsewhere in the world could once again cause homegrown problems to lenders in those places. And even if that didn't happen, a commercial-property-related meltdown in the regional banking system in the US that dragged down equities and bond yields there would presumably have spillover effects to financial markets around the globe.

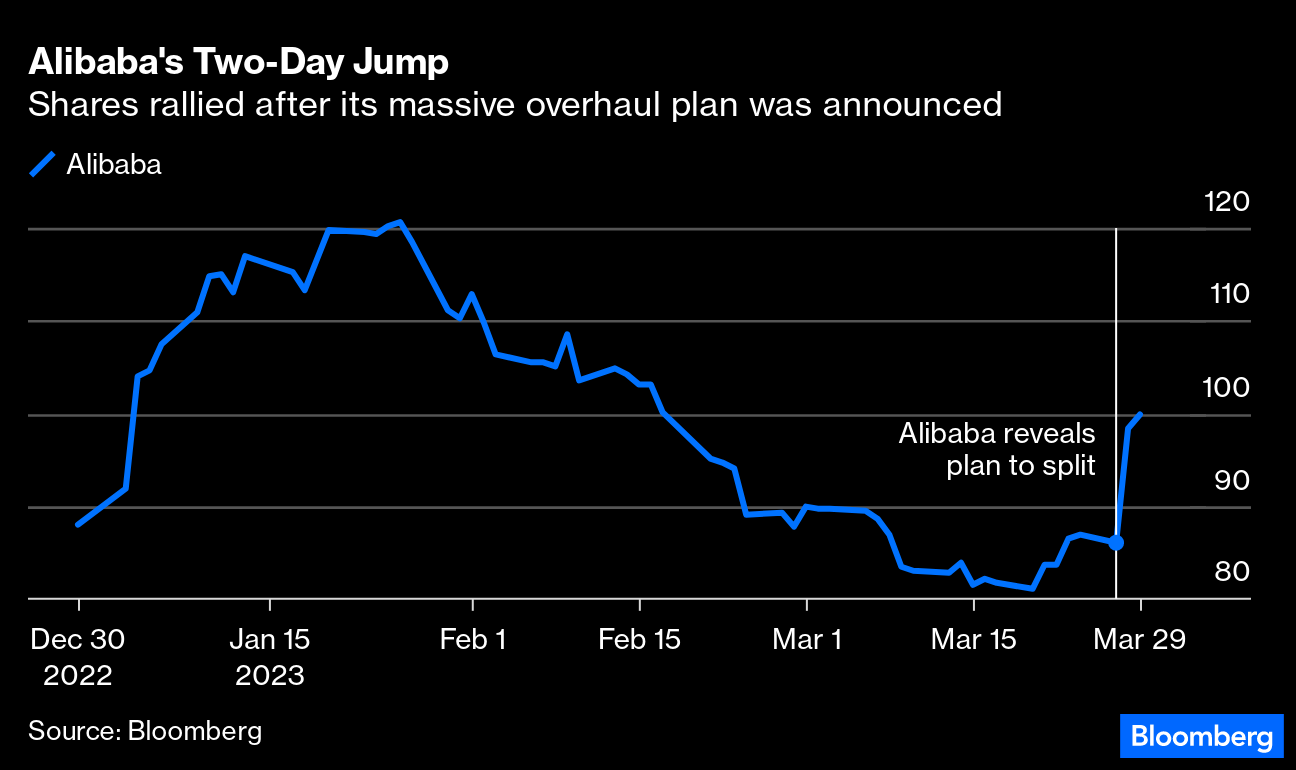

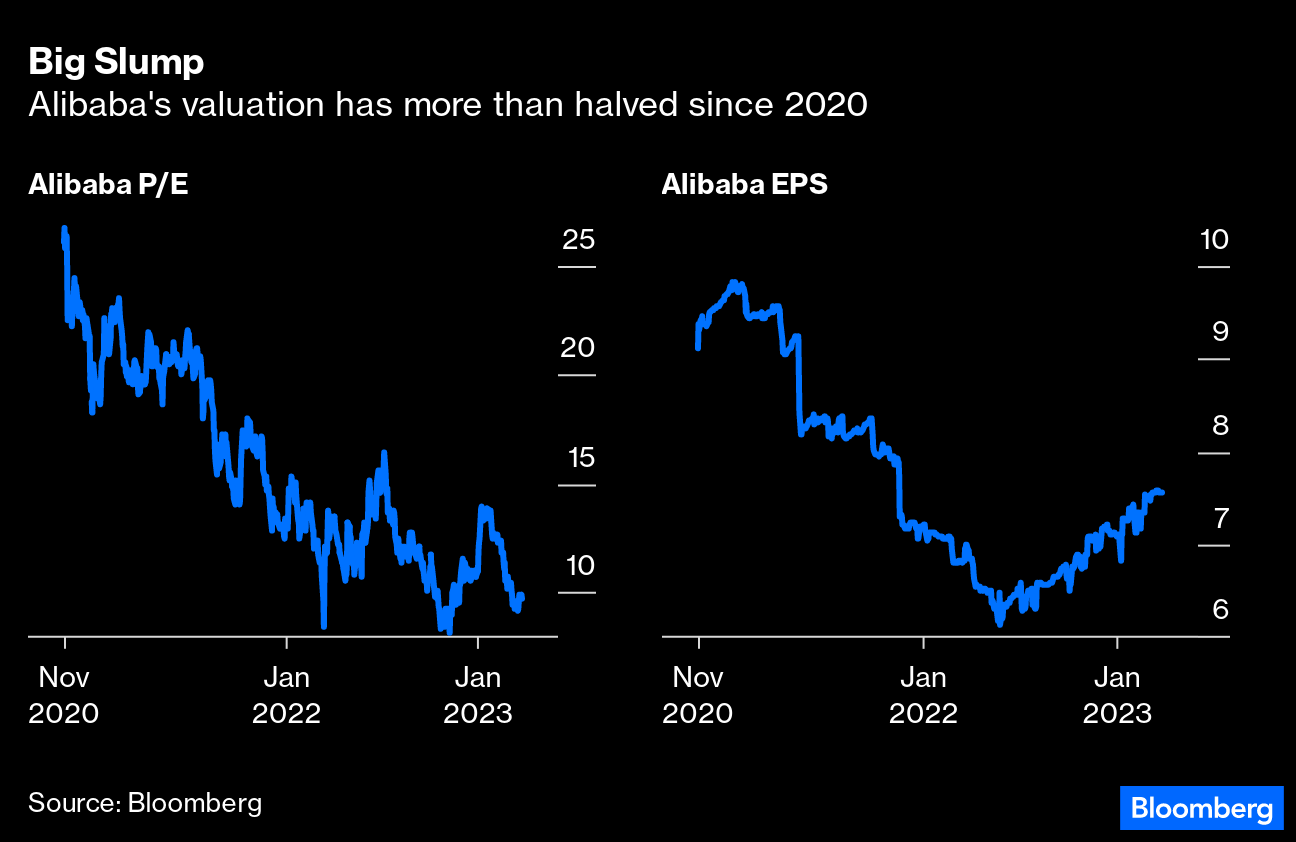

Perhaps it's best to view the return to optimism as the tip of another in a series of diminishing waves as we all assimilate some banking failures that came out of nowhere. At this point, it looks very much as though the optimism may have gone too far, but it equally looks as though the pessimism had indeed been overdone. Tectonic shifts seem to be under way in China after Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. this week announced that it would break up its roughly $220 billion empire into six units. The news sent the shares on an instant 13% rally, the most since November. It's currently up 16% for the week.  Key to the changes — the biggest overhaul in the company's history — is the fact that the offspring can individually raise funds and explore their own initial public offerings. Not only will this new plan boost a lackluster capital markets sector that has seen public debuts dwindle since the pandemic. It will also serve two goals: appeasing Chinese regulators who have ramped up their crackdown against "too big to fail" tech firms, and unlocking more value for the firm that has traded at a much cheaper valuation than its rivals. (For instance, Alibaba's forward earnings multiple rates the stock cheaper than CLP Holdings Ltd., a utility company, and just on par with China Telecom Corp. For a company of Alibaba's scale, competitive position and growth potential, this should be absurd.)  The big announcement came after regulators vowed to boost support for private firms after years of scrutiny that has left investors bruised, and put a lasting dent in market sentiment toward China and its corporate governance. The clampdown all started somewhere around the sudden halt of Ant Group Co.'s public debut in November 2020 — then on the cusp of becoming the biggest stock-market offering the world had ever seen at roughly $35 billion — much to the surprise of everyone. Jack Ma, its celebrated billionaire founder, likely included. Reaction was swift. Alibaba, which owns a third of Ant, plunged by the most in almost six years in New York, erasing almost $3 billion from Ma's fortune. Authorities were mum about the issues behind the suspension, simply noting that the IPO couldn't go through due to a "significant change" in the regulatory environment. Even after this week's bounce, Alibaba's share price remains 68% below its peak before the curtain fell. Since then, the mood has darkened in the Asian superpower as the administration has grown more autocratic. That's why this week's turn of events has been welcomed by many. Here's Bloomberg Economics' Chang Shu and Eric Zhu in a Wednesday note: Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.'s restructuring may indicate the government has found a path for regulating the tech sector and taken a more constructive approach to private businesses. If this is the new way forward, it could be a catalyst for private-sector confidence revival — propelling growth.

Also this week, coincidentally or not, Ma surfaced at a public school in Hangzhou, after more than a year of traveling overseas. His last high-profile event was in October 2020, when he criticized regulators during a speech in Shanghai. Shortly after, Ant's IPO was shelved. To Andy Rothman, investment strategist at Matthews Asia, the changes have broad significance as President Xi Jinping defines his approach to the private sector: I believe that this was a carefully coordinated announcement – along with Jack Ma's return to China the day before – with senior Party leaders. New Premier Li Qiang, who has known Ma for many years, probably led the effort for Xi... It also suggests the government is ready to resume IPOs for the tech sector, presumably including in overseas markets.

It remains to be seen how "Six Baby Babas" — as Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tim Culpan put it — will play out. Political relations with the US and western Europe are at a low ebb and that won't help. But if successful, this likely will serve as a blueprint for Chinese tech giants such as Tencent Holdings Ltd., JD.com Inc., and Baidu Inc. Perhaps US regulators will take notice. The US has some enormous and unhealthily dominant internet groups of its own that politicians on both sides of the aisle would like to split up. Given how Washington has publicly scrutinized tech behemoths like Amazon.com Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc., it's just possible that the Baby Babas could help determine the fate of the FANGs. — Isabelle Lee On the subject of breakups: Ted Lasso needs to roll over. You can listen to Ted's Breakup Mix if you like. But you're better off with the crowd-sourced Survival Tips Breakup Mix on Apple Music, or Spotify. A lot of Points of Return subscribers have been through breakups, which at least confirms that readers are living life to the full, and running the risk of disappointments along the way. It's quite a motley range of songs, by both men and women, some of whom were left and some of whom ended the relationship, some of whom remain very, very angry and some of whom are as lovelorn as ever and very sad. I haven't included much very recent music ("Good For You" by Olivia Rodrigo would have been an obvious candidate), mainly because Points of Return's readership tends not to listen to the stuff that's come out recently. It also doesn't include late-breaking nominations that ranged from Jacques Brel to Leonard Cohen; sorry about that.

I'm glad this has been of interest. It does make a change from price/earnings multiples and yield curves, and it seems we're all thankful for that. All further feedback will be gratefully received. More From Bloomberg Opinion: |

No comments:

Post a Comment