| Just when Wall Street thinks Americans are feeling better about the economy, they are reminded yet again that fears are hard to shake off. US consumer confidence unexpectedly fell in February as surging services prices on top of recession risks took their toll, even though the labor market stayed strong. The Conference Board's index slipped for the second straight month to 102.9 from 106 in January, notably bucking the median forecast in a Bloomberg survey of economists that called for the gauge to rise to 108.5. "Both current confidence and expectations for the future — arguably more important in guiding behavior — fell noticeably," said Ataman Ozyildirim, senior director of economics at the Conference Board: That must be music to the ears of the Federal Reserve. The index's decline should not really be such a surprise given a backdrop of pessimism on multiple fronts in the next six months: jobs, wages, and the macroeconomic environment. José Torres, senior economist at Interactive Brokers, called the report "ice cold," favorable for fighting inflation, but at a significant implied cost in the form of declining consumer spending. And even if layoffs — largely in tech, though evident in other pockets of the workforce — have so far been contained, it does not help sentiment, said Emily Leveille, portfolio manager at Thornburg Investment Management. She added that inflation, which remains persistent and elevated, continues to eat into people's budgets and erodes households' purchasing power. Still, the unemployment rate has tumbled to a 53-year low, with the share of people who said jobs are "plentiful" surging to 52%, the highest level since April. Those who say jobs are hard to get edged lower. Jeffrey Roach, chief economist at LPL Financial, said the numbers reinforce expectations of a strong jobs report at the end of next week. The labor market, he said, is still running hot, with plenty of opportunities for workers. That's not great for the Fed. As Chair Jerome Powell said earlier in February, if the employment situation stays hot, "it may well be the case that we have to do more" by hiking rates. What's more concerning is that while people are getting nervous about the overall environment, the survey shows a "significant improvement" in perceptions of the labor market, according to Rubeela Farooqi, chief US economist at High Frequency Economics: The net percentage of people rating jobs as "plentiful" — those saying jobs are "plentiful" minus those saying they are "hard to get" — rose to 41.5 in February from 37.0. This is the highest level since April of last year. The data are in line with the recent decline in the unemployment rate to the lowest level since 1969. While consumers have a positive view of labor market conditions currently, their perceptions about the outlook for jobs and incomes over the next six months deteriorated in February.

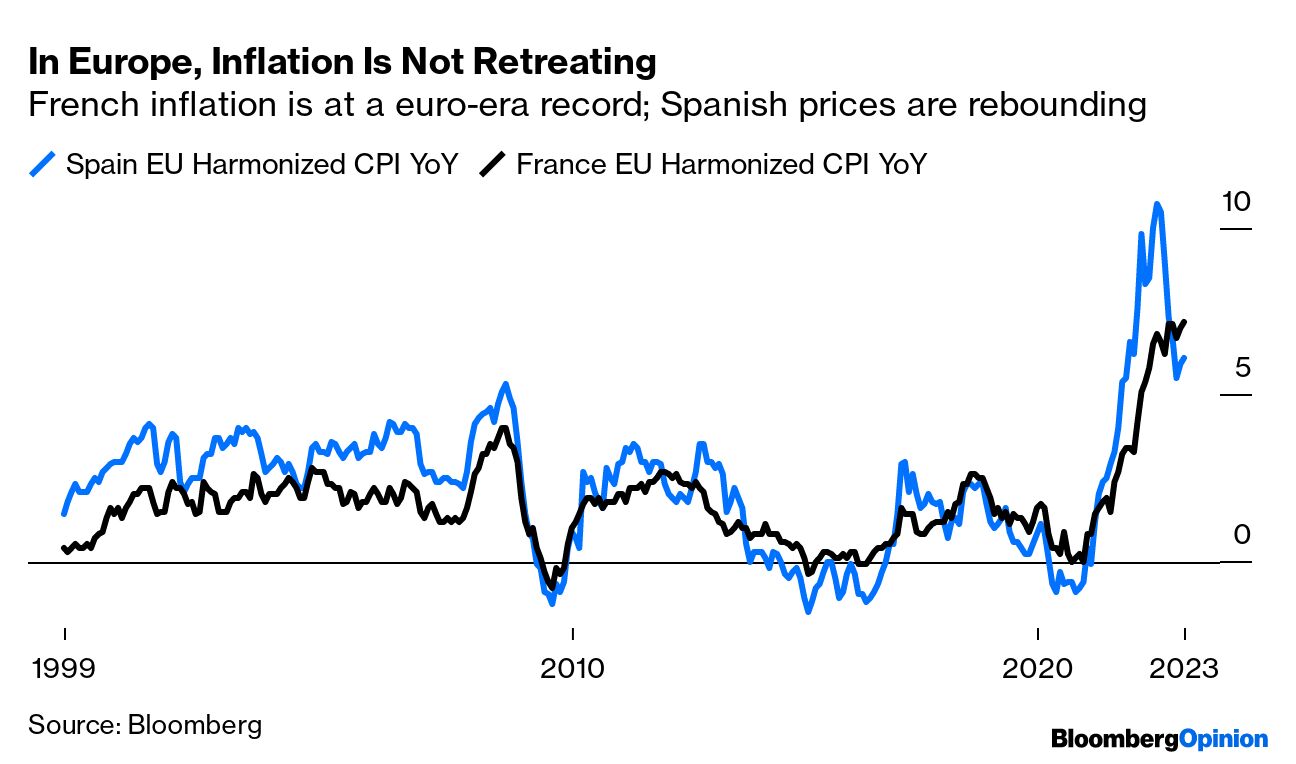

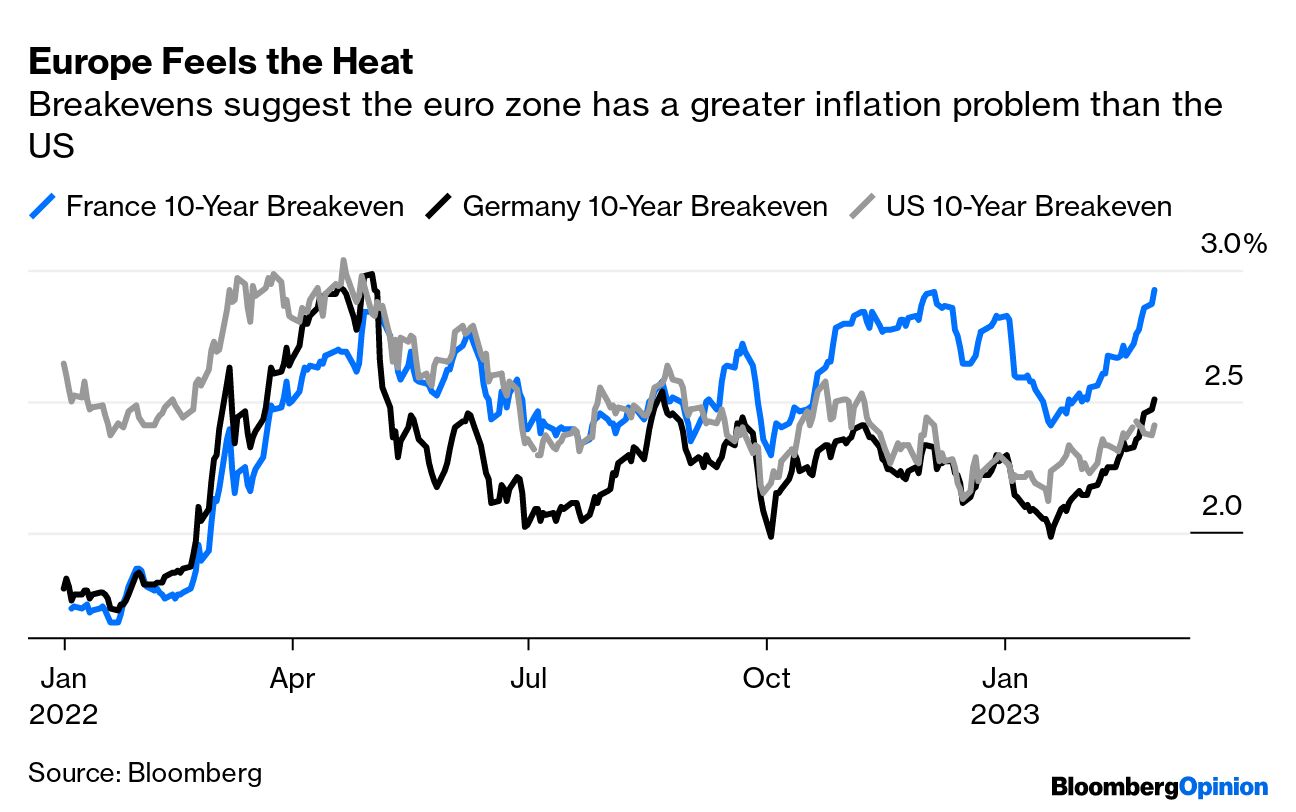

Ever since 2022, the Fed has been determined to curb inflation even if it tips the economy into a recession. Repeatedly, policymakers have insisted that they are hell-bent on bringing it back down to 2%. The bond market is taking its cues from the central bank, with traders now pricing US rates to peak at 5.4% this year, compared with about 5% just a month ago. Perhaps the Fed's messaging is trickling into the economy. Inflation expectations fell in February to 5.4%, the lowest since April 2021. Roach said this is good news for policymakers concerned about the risks of "unmoored inflation expectations." One catch though: the Conference Board measures stand in contrast to the University of Michigan survey: Consumer sentiment climbed to its highest in more than a year on upbeat views of current conditions. That was highlighted by Win Thin, currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman. His verdict? "Given how consumption has been coming in strong, I get the sense that Michigan may be telling the truer story." The division between the two surveys almost seems to encapsulate the debate between a hard and soft landing. The narrative that the economy wouldn't need to land at all gained traction in February; the Conference Board numbers call the optimistic story into question. That opens up the issue for the next week or so; is it possible that the startlingly strong data for January was a fluke? If it was, then the numbers for February, which start to flow on Wednesday, should at least begin a process of correction. To quote Marc Chandler of Bannockburn Global Forex, we need to know "whether the US January data reflects a reacceleration of the world's largest economy or whether it was mostly a payback for extremely poor November and December 2022 data and seasonal adjustments and methodological distortions... The issue is unlikely to be resolved in the week ahead, but it may begin pointing to the direction ahead." Chandler warns that the "no-landing" and "soft-landing" scenarios stand in flat contradiction to many reliable recession indicators, such as the inverted yield curve and the swift fall in leading economic indicators. To believe in them also implies that rising default rates on car loans and the tightening of lending standards, which show up in the Fed's official survey, can be ignored. "While this is all possible," says Chandler, "it seems patently unlikely. Expect the February data to begin casting shade on the January-spurred optimism." But stop the press: Just before sending this, China's February PMI data came out. These are surveys by different organizations, covering manufacturing, services, and a composite of the two, and they all agree that the economy is as strong as it's been since Covid-19 first hit in the spring of 2020. The snapback after Covid-Zero restrictions were lifted late last year has been remarkably swift — whatever US data lie ahead, the China reopening narrative looks mighty strong: — Reporting by Isabelle Lee Europe has dodged a bullet in the first two months of the year. The much-feared energy crisis hasn't happened, in large part because of good weather. That might presage a longer-term climate crisis, but it's great news for now. However, despite this big assist from the natural world, inflation is not coming under control. Spain and France released new inflation data Tuesday, and both showed annual price rises increased again. This chart shows inflation in the two countries since the inception of the euro at the beginning of 1999:  That is in the rear-view mirror, but it's having an effect on expectations. As 2022 dawned, breakevens in the bond market — the implicit inflation forecast that can be derived from the difference between fixed and inflation-linked bond yields — suggested that Europe's big economies still had little to worry about. Over 10 years, French and German inflation was projected to stay below 2% on average. While there was nothing like panic, the US was clearly perceived to have a greater problem. That has now completely reversed. French breakevens are closing in on 3%, while Germany's now exceed those of the US. The long deflationary European slump, which saw years of negative interest rates, is definitely over. Or at least that's what bond investors think:  This is beginning to have an effect on rate expectations. Entering this year, overnight index swaps, as measured by the Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities (WIRP) function, saw the European Central Bank hiking up to about 3.5% and then stopping. In the last month, that has shifted, and there is now a serious belief that the ECB could get to 4%: The US data still probably matters more. But the implications of a much more durable European inflation problem shouldn't be ignored. Britain's vote in a referendum to leave the European Union happened in June 2016. After much melodrama, the formal exit finally happened in early 2020, on the eve of the pandemic. And now it's back in the headlines as the UK's fifth Conservative prime minister since the referendum was called has reached a new agreement with the EU that aims to make workable the compromise reached over the treatment of Northern Ireland, the only part of the UK that shares a land border with the EU. As people on both sides of that border desperately want it to stay as open and porous as possible, and a hard-won relative peace in the region is at stake, this matters. Perhaps it's healthy that most people around the world, and even the UK, no longer seem to be much engaged with the issue. Google search data shows a spike in interest at referendum time, and in the subsequent British political crises as MPs tried to work out how to enact the electorate's instructions. This latest bout of activity has had much less impact: This is at least in part because Rishi Sunak, the current British premier, seems to have succeeded in at last turning this issue into a technical one to do with the nuts and bolts of trade policy, rather than a frantic battle over sovereignty. Bloomberg summarizes the salient details here. The entire episode demonstrates the folly of the Brexit enterprise from the start; it's very hard to see what benefits could justify so much hassle. And Northern Ireland is a very small part of the UK economy. However, the pound enjoyed quite a rally on the news. On a trade-weighted basis, the seizure that greeted Liz Truss's disastrous mini-budget last year is now well in the past, and sterling is again showing signs of moving into an upward trend: Does the Northern Irish agreement (known as the Windsor Accord) really change things that much? Probably not. This was the gloriously dismissive comment of the foreign-exchange team at Brown Brothers Harriman: We suspect the deal will eventually be passed but there is absolutely nothing to get bullish about. The agreement simply avoids a potential trade war as the UK had threatened to unilaterally change the Brexit deal, which would trigger sanctions from the EU. When all is said and done, the UK has still left the EU and will continue to pay the price economically for this choice. In recent months, we have gotten all sorts of studies that have quantified the huge negative impact of Brexit on UK productivity, growth, inflation, etc. Those costs aren't going away after this deal.

Fair enough. But the intangible sense that the UK's body politic, on both sides, is now prepared to be constructive about Brexit and treat departure as a fait accompli, along with the evidence that the EU is also now more conciliatory, does matter. The opportunity cost of the seven years that the UK has wasted wrestling with its attempt to exclude itself from a huge trading bloc on its doorstep is incalculable. But it's a sunk cost now. If Sunak is proved to have ushered in a post-Brexit psychology, just as the resignation of Nicola Sturgeon as Scotland's first minister also sharply diminishes the risk that the UK will be splitting, that is definitely reason to buy the UK. Now to see if the europhobic branch of British politicians can calm down and let the agreement pass. Excuse my digression, but I have some historical speculation. Britain, and Europe, might have been very different and also much better off without a classic piece of political skulduggery the week after the Brexit referendum. Boris Johnson, having led the campaign to leave, was expected to run for the prime ministership, and win. After some bizarre back-room shenanigans, his formerly loyal lieutenant Michael Gove announced that he would run instead, saying he had realized (literally overnight) Johnson was not a fit person for the job. (To be fair, he was right about this.) Johnson announced that he would not after all be a candidate a few hours later. Following a few days of nastiness, with those who had urged Brexit unable to coalesce on a viable candidate, Theresa May won the job. May had campaigned against Brexit. This made her anxious to prove that she was prepared to do the job properly, and she adopted a slogan of "Brexit means Brexit." This turned out to mean a "hard Brexit" in which the UK exited both the EU customs union and its single market. Given her history as a "Remainer," May was probably right to judge that she didn't have the political latitude to go for a less economically damaging version of Brexit. The "Nixon to China" principle applies here. A sensible compromise on Britain's exit could only be reached by a committed Brexiteer (just as only a hard-core Cold Warrior like Richard Nixon could make friends with Chairman Mao). Johnson lacks any obvious guiding principles, but he pooh-poohed the notion that Brexit would mean leaving the single market during the referendum campaign. Unlike May, he would have had the space to decide that after a narrow result — with 48% of voters wanting to stay in the EU — a relatively "soft" Brexit made the most sense. He could probably have forced it through. May, although she is a far more decent and principled politician, ended up impaled on the contradictions of a "hard Brexit" in no small part thanks to Johnson's provocations. Once she had fallen, Johnson could claim to have "got Brexit done" but only through a compromise that sold out his Northern Irish allies, and which proved unworkable. It would have been better if he'd been given the job in 2016 — and with any luck, Sunak's accord will finally finish any chance that he ever gets the job again. The break between Gove and Johnson, both presidents of the Oxford Union debating society in the late 1980s, and also Oxford contemporaries of David Cameron, the prime minister they felled, bore all the marks of the irresponsible political chicanery that they could indulge in safely while they were students. I don't see how anyone in the investment world can model the chances of such a falling out, but it's unsettling to think of how much proved to rest on petty personal issues. Also, full disclosure, as I was a contemporary of theirs, it's deeply chastening to see how badly my generation of Oxford graduates has let down their country. And despite this, both Truss and Sunak also — like me and David Cameron — have degrees in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from Oxford. Not good, at all. End of digression. Here's a recommendation for some great long-form reading. My friend and former colleague Dan McCrum bore the gamut of unbelievably aggressive attempts to silence him as he uncovered a massive fraud at the German company Wirecard. He was proved completely right. Now, the New Yorker has a great narrative telling the story. It's worth reading. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Mexico Is Flashing Warning Signals to Washington: Eduardo Porter

- Money Doesn't Make America's Economy Go Around: Bill Dudley

- A Sick America Can't Compete With China: Adrian Wooldridge

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment