| There's a lot of news to come before this week is out, but Europe is shaping up to be the epicenter of whatever happens. The range of possibilities facing the eurozone — which after all still has to contend with a war raging on its borders — is far wider than for the rest of the developed world, while the European Central Bank faces arguably the most awkward job. That in turn will have repercussions everywhere. To prove this, the big data point to move markets on Monday was Spanish inflation. This is not normally regarded as a "first-tier" number, and over time economists have been very good at predicting it in advance. But last month's was a nasty surprise. Not only did Spanish inflation rise a little, rather than continuing a marked downward trend, but it also deviated from forecasts by the most in any month since 2010: Any reminder that a peak in inflation doesn't guarantee that it will then go down in a straight line is unwelcome. After all, huge amounts of money has been wagered on the proposition that the Federal Reserve will have started to cut rates long before the end of this year. If European inflation isn't reliably falling, that looks a dubious proposition. According to Edward Moya of Oanda Corp.: Disinflation trends have been firmly in place across the US and Europe, so Spain's hot inflation report is a big red flag that the rest of the eurozone might show inflation is already proving to be stickier than what the market was expecting. ECB hawks won't have trouble pushing for a half-point rate rise this week.

A further issue is the possibility of a widening disjunction between the US and the eurozone, which would in turn have implications for the dollar. At this point, overnight index swaps — as measured by Bloomberg's World Interest Rate Probabilities function — show great certainty that the ECB will be tightening and then tightening some more this year, while the Fed is nearly done: Those with long memories will recall the frantic trading in the summer of 2008 as the ECB surprised the Fed by deciding to hike rates. A divergence this direct could be very problematic. As it stands, US yields remain above those in Germany, although the Spanish inflation figure helped narrow the gap sharply (which should ultimately weaken the dollar against the euro): Beyond this, the European liquidity position is very different, in large part because the Fed was far more aggressive in releasing liquidity in 2020 and 2021. In the US, money supply as measured by the broad M2 definition is now actually negative year-on-year; the same is not true for the eurozone: The ECB has said that it intends to continue with quantitative tightening, or QT — sales of bonds to reduce the amount of cash in circulation and drive up yields. More may be needed. But it may have a greater problem doing so than the Fed (and the same applies to the Bank of Japan), because long-term bond yields were actually negative for several years. Retreating from such easy conditions could be hazardous. This is the judgment of Peter Boockvar of Bleakley Financial Group LLC:

I still remain worried about how the ECB and BOJ are going to pull off further tightening and QT... since both Europe and Japan were the epicenters for the epic sovereign bond bubble. The Italian 10yr yield is quietly at a three-week high, up 9.4bps today to 4.19%.

The greatest issue confronting the eurozone, however, is energy. In recent weeks, it has dodged a bullet. Surging natural gas prices reflected fear of a humanitarian crisis this year that Europeans would prove unable to heat their homes. But the weather has been unusually gentle, and natural gas prices have plummeted. They are now lower than on the eve of the Ukraine invasion and have moved almost in line with gas prices in the US: Naturally, the risk of a social breakdown colored perceptions of the region's economic performance, and in particular has had a dramatic effect on the performance of eurozone equities. The following chart from London's Capital Economics shows that their performance relative to the US has had an almost perfect inverse relationship with the price of European natural gas: A bullet dodged is a bullet dodged, and it's very reasonable for risk assets in the region to rally as it becomes clear that all-out crisis can be avoided. Also, plainly, lower energy costs reduce overall inflation. But that doesn't mean that all is over. Gas prices started to fall before it grew clear that the winter would be exceptionally mild. That reflected changes made by business that will have an ongoing impact. This somewhat chilling judgment is from Robin Brooks, chief economist of the Institute of International Finance: Natural gas prices in Europe have fallen substantially, making it tempting to think that the energy shock is over. We do not share that conclusion for the following reasons. First, gas prices are still a lot above their long-term averages. The negative terms-of-trade shock is therefore still very large. Second, prices fell because of substantial changes in demand, with gas-intensive manufacturing a lot weaker than pre-shock. The energy shock in Europe remains substantial and is ongoing.

As Brooks demonstrates, the fall in production by the German chemical and pharmaceutical industry up to the end of November was extreme: Further, while the possibility of a tragic winter has receded, Europe's natural gas imports remain far lower than before Russia invaded and the economy will take years to adjust to the new reality. This IIF chart also goes up to the end of November: This plainly makes growth far more difficult to sustain. But if we look at German manufacturing orders compared to industrial production, it's not at all clear that a sharp fall in demand after the pandemic will lead to recession, because German industry never managed to boost its output to deal with the post-pandemic spike in demand: If you think you can work out how this resolves, well done. The rebound for European assets that we've already seen is amply justified by the warm weather reprieve, and the rally in the euro to date can be satisfactorily explained by evidence that the ECB will have to be much more aggressive than the Fed this year. The popular expectation that Europe should continue to outperform this year is reasonable; but it's no certainty. As we enter the final countdown to the first central bank meetings of the year, it's the ECB that has the most consequential decisions ahead of it. It has been months since the first wave of massive layoffs began among tech companies, which saw some behemoths like Amazon.com Inc., Google parent Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp. announce job cuts north of 10,000. In total, the layoffs have reached more than 100,000 jobs since the beginning of 2022. The news has been shocking and painful, prompting many to alter their views of the once unstoppable and seemingly limitless industry. That might be overreacting. To some commentators, it was to be expected — as harsh (and sad) as that may sound. After all, tech firms were on a relentless hiring spree for most of the Covid-19 pandemic, with some firms even doubling in size. In many cases, the layoffs only rewind the clock by about a year — a sentiment expressed by Carol Schleif, chief investment officer at BMO Family Office: The layoffs we have seen in the tech industry in recent weeks are a small percentage of the hiring that has taken place at many of these companies over the past few years, and yet the valuations of many large tech companies seem to imply Armageddon.

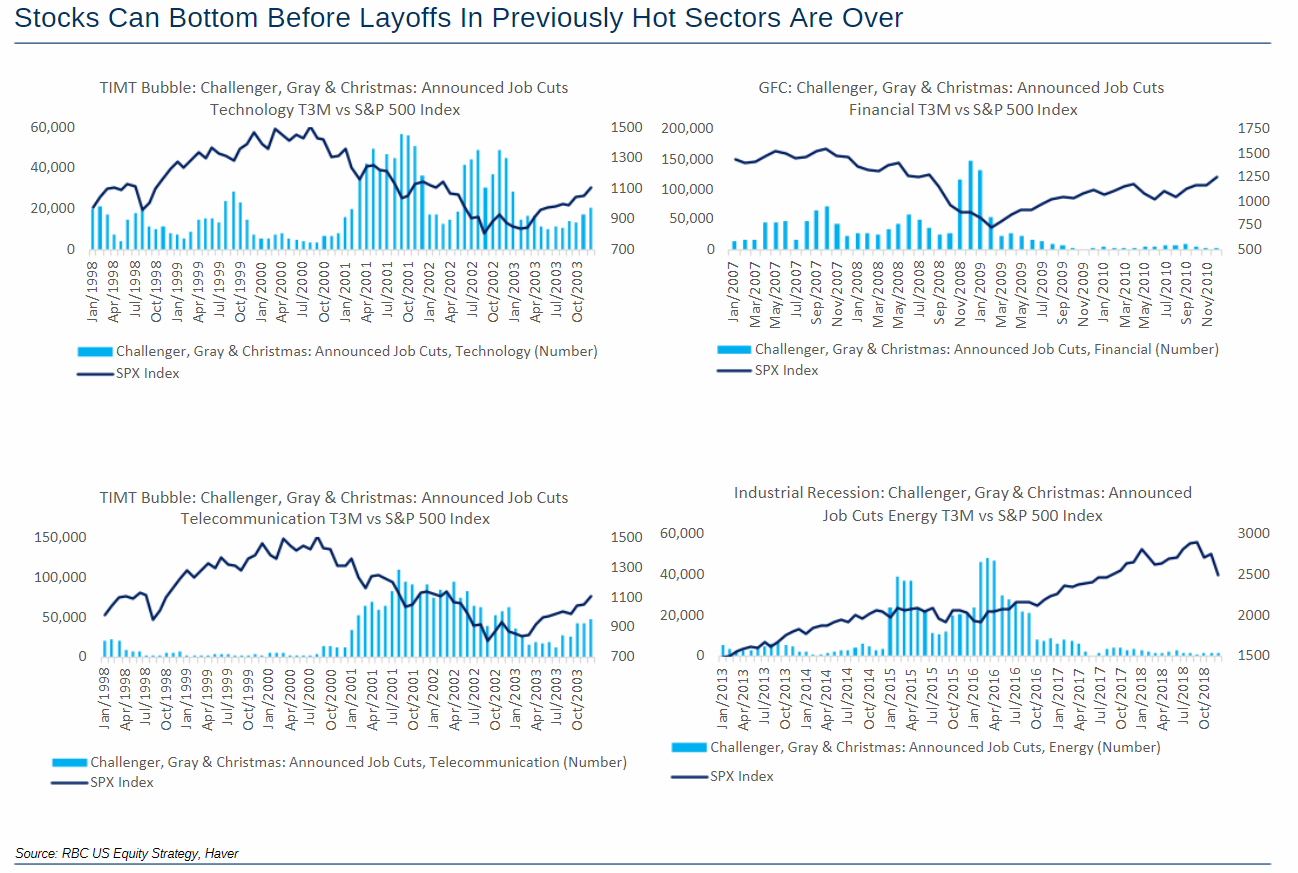

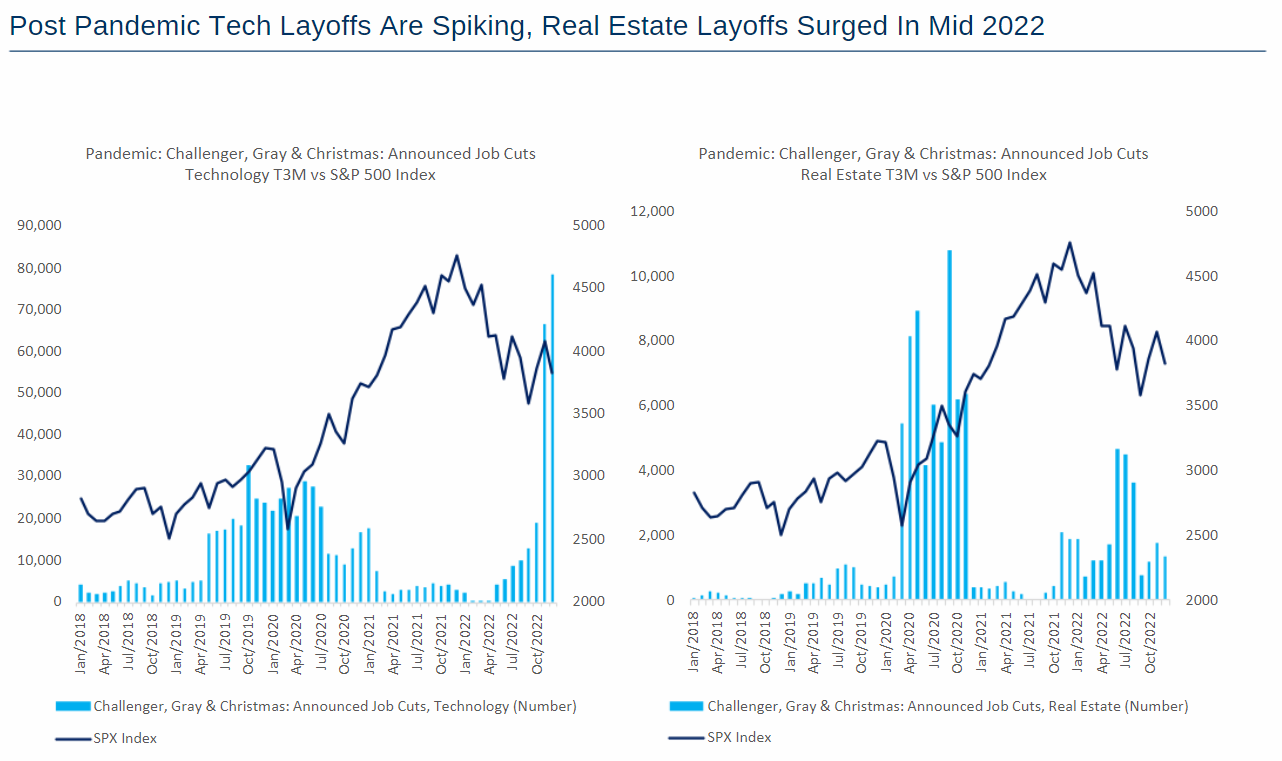

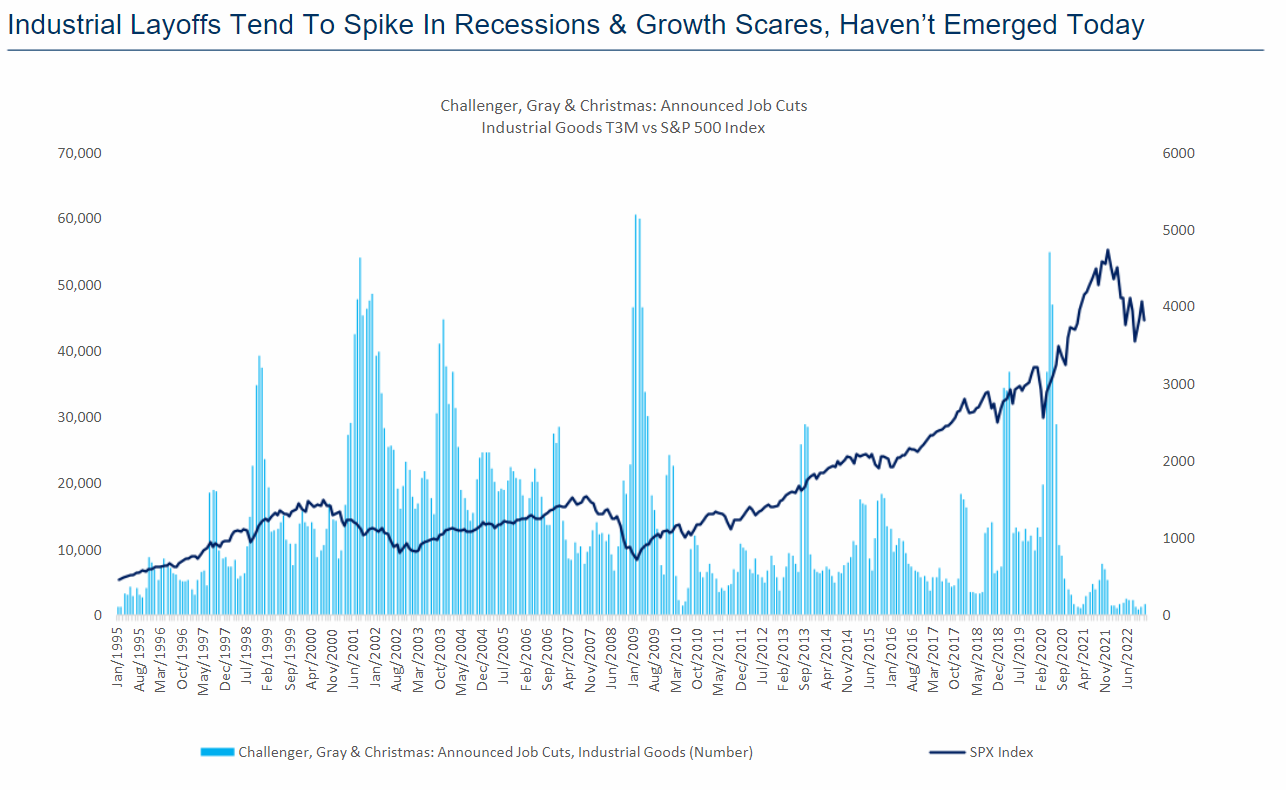

The real-world implications for those who lose their jobs are severe and should not be wished upon anyone. Yet through a markets lens, layoffs of this magnitude are common as part of the bottoming process of equities. How so? RBC Capital Markets' head of US equity strategy, Lori Calvasina, wrote that the stock market often bottoms well before layoffs are finished in industries of excess. Therefore, it's not necessarily surprising that the market has rallied on some apparently awful news. But while it's always difficult to tell exactly where we are in the cycle, the past performance of US equities during periods of layoff suggests that the end of the bear market is not yet in sight. Calvasina and her team analyzed layoff trends in the following sectors and periods: tech and telecom around the TMT/dot-com bubble in 2002; financials around the Global Financial Crisis in 2008; and industrials and energy around the 2015-2016 Chinese growth scare. Then they compared all these to S&P 500 index levels, as seen in the graph below:  Source: RBC US Equity Strategy, Haver In some instances, it's evident that the bottoming of equities happened at around the same time as big layoff spikes in the concerned industry. In others, it wasn't until a second spike that stocks found a permanent floor. That's what happened with tech around 2002 and with energy around 2015-2016.  Source: RBC US Equity Strategy, Haver With today's tech layoffs, the bottoming of equities is still in question. While US stocks declined Monday, with the Nasdaq 100 suffering its worst day in more than a month, the index is still up nearly 9% year-to-date, while the S&P 500 is up almost 5%: Perhaps it's best to regard layoffs as a necessary condition, rather than any kind of sufficient condition, for a market bottom. Here's Calvasina: With tech layoffs spiking now, and real estate layoffs having spiked last summer, it's hard to say conclusively whether the data supports the idea that US equities bottomed in October. But the data does give us one more thing to check off in our list of things that we believe need to happen for the stock market broadly to bottom.

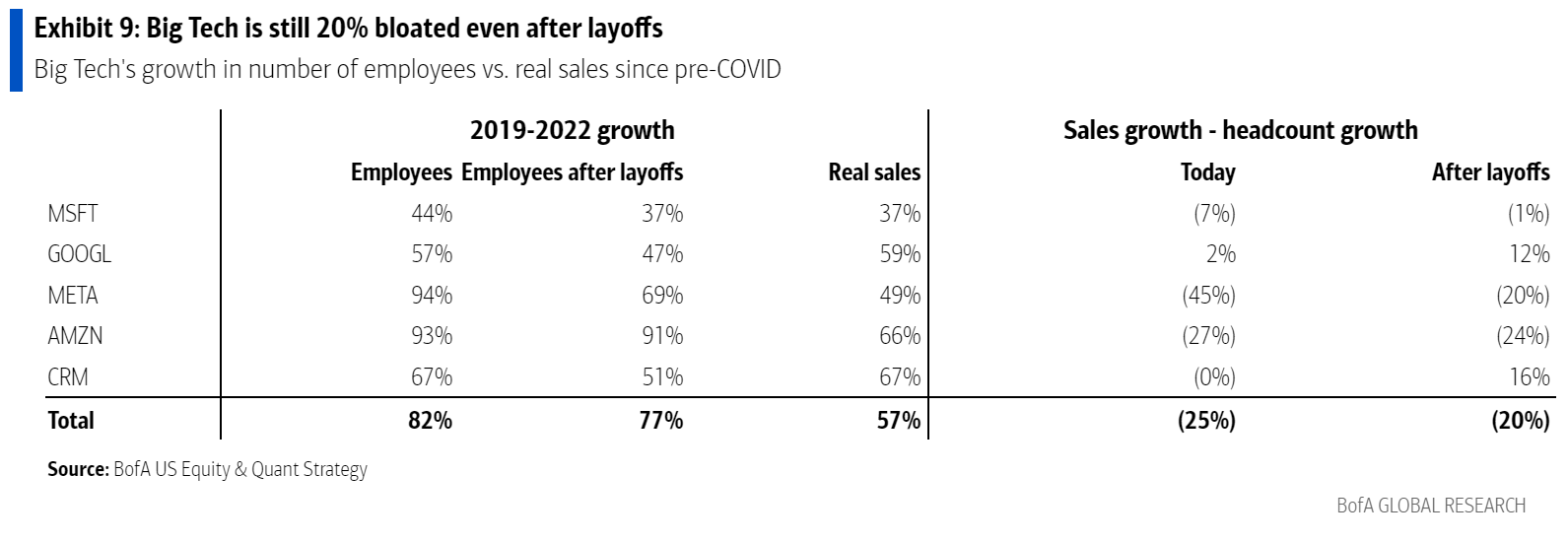

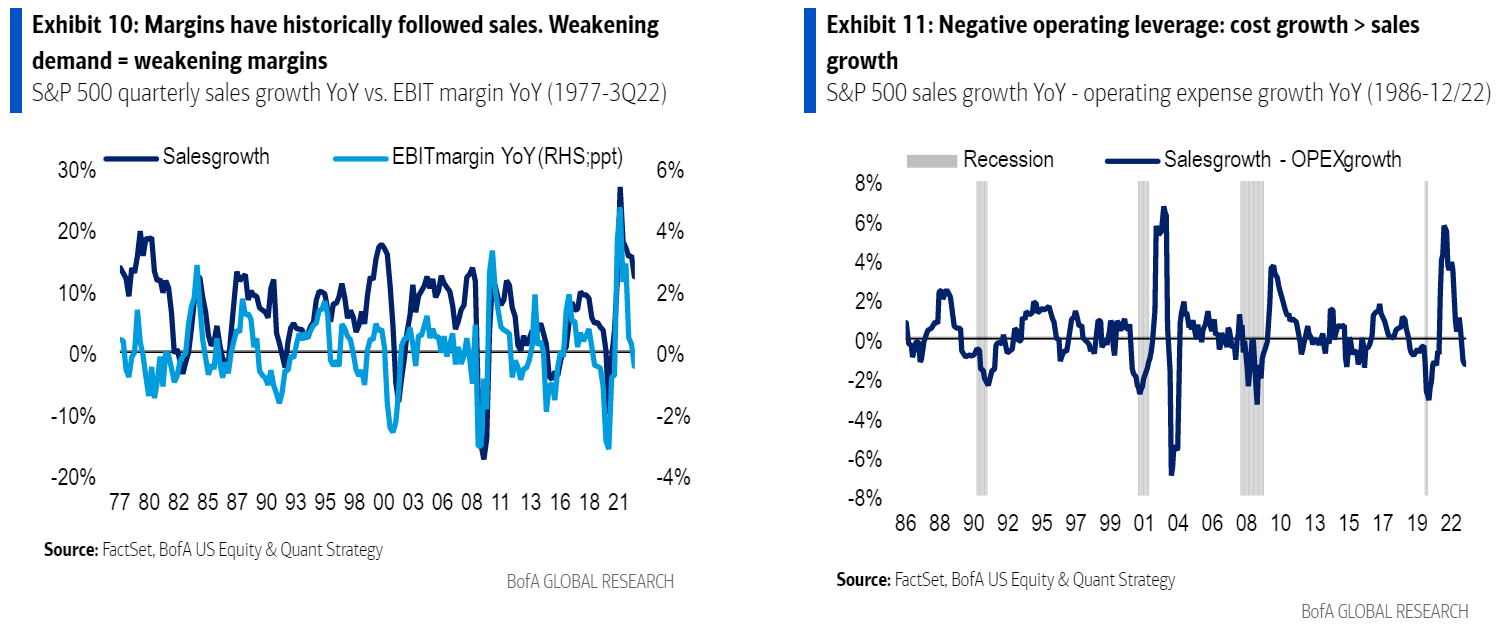

For some, such as Bank of America's strategists led by Savita Subramanian, tech may have much more to cut because the industry remains bloated. While the hiring spree in the past three years drove employee growth of 80%, real sales only grew 60% over that period. The data seem to imply that even after the first big round of job cuts, some companies are still 20% too big on average.  Source: Bank of America Furthermore, cost cutting of 1.7% of sales thus far, they said, should help to minimize margin compression. While this is true as far as it goes, sales have historically been a bigger driver of margins. BofA strategists see weakening demand and negative operating leverage as significant contributors to margin pressure.  Source: Bank of America All of this adds up to a complicated impact for policymakers. Asked by Bloomberg's Peyton Forte if the Fed would be afraid of layoffs spreading to other sectors, Vincent Reinhart, chief economist at Dreyfus and a long-time Fed official, replied: "They want to slow aggregate demand growth to alleviate pressure on resources — that is associated with a slowing in the pace of hiring and a pickup in layoffs. Tech firms are the individual observations that make the macro data points the Fed needs to see — employment slowing." Reinhart adds that it's just possible these layoffs don't have broader ramifications across the economy because they're sectoral. The official data are based on a survey, and when published they come with wide "confidence intervals." When layoffs are centered in particular sectors, the risk of miscounting grows greater. To quote Reinhart: The answer to the question — could the data be mismeasured — is always yes. Maybe in the history books it'll become clearer. I was struck by fact that the ADP series last month said the big job losses had been at big firms and firms on the West Coast. Gee, that sounds like tech layoffs to me. A lot of the employment gains we're seeing now are catch-up still from the pandemic separations. What we're seeing in terms of layoffs is the hiring during the pandemic looking inappropriate. Why don't we see it in the macro data? Well, because it's a sectoral story. If you hire too much in the pandemic, you're laying off now. If you couldn't get workers then and have had trouble since, you're still hiring now.

Another key issue, Reinhart reminds us, is that tech is important as a source of productivity growth and adds much value to the US economy — "but it's not that big an employment sector." Big industrial companies, meanwhile, tend to cut jobs during periods of economic stress, but presently, according to Calvasina, layoffs in the sector have remained extremely low: The lack of major layoffs in the industrial segment of the economy so far supports the soft landing thesis, in our view... given the strong levels of demand and backlogs that we continue to hear about from publicly traded industrial companies. If the US skirts a true recession, we continue to think it will be in part because the industrial economy is providing a bridge to the other side.

If big industrial job losses can't be avoided, past history suggests that the rebound for the S&P 500 as a whole would come after those layoffs:  Source: RBC US Equity Strategy, Bloomberg; as of 1/27/22 For now, initial unemployment claims are at their lowest since last April, and the labor market continues to look tight. Confidence in lower rates and stronger stock valuations would be helped by some more weakness in Friday's jobs report. — Isabelle Lee  | Let's talk tulips. One of my favorite podcasters, Tim Harford, has devoted an episode of "Cautionary Tales" to denouncing the "myth of the million-dollar tulip bulb." He takes aim at Charles Mackay's classic Extraordinary Popular Delusions and The Madness of Crowds, a great work of 19th-century financial journalism that introduced us to the Dutch tulip mania of the 17th century. Harford channels a lot of interesting revisionism. The key point, which I think is well made, is that the mania didn't have the major repercussions on the Dutch economy that Mackay presented. But I'd be careful about the word "myth" — tulip bulbs did reach absurd prices, and went ballistic in large part thanks to the availability of leverage and the existence of tulip derivatives. It's still a very useful incident to study, and even finds its way into the canonical book on investment bubbles, Charles Kindleberger's Manias, Panics and Crashes. Like many other absurd speculative bubbles in the years since, it wasn't anything like as damaging as when US housing burst in 2008.  A bubble for the ages. Photograph: Bloomberg My favorite book on the subject is Mike Dash's Tulipomania, which you can read like a novel. And of course, you could always get the tulip mania T-shirt. Meanwhile, listen to Harford's podcast, and maybe to some other episodes as well. They're very good. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? {OPIN <GO>}. Web readers click here. |

No comments:

Post a Comment