| Hello. Today we look at the implications of rising debt burdens, a problematic pay deal at the Bank of Japan, and the downside of early retirement in the US. The cheap-money era is over for households, businesses and governments. Combining all three, the Institute of International Finance puts the total owed at $290 trillion, up by more than one-third from a decade ago. As Liz McCormick, Alexandre Tanzi and Enda Curran report here today in Bloomberg Businessweek, even though debts have retreated from their pandemic peak, the risks are intensifying as borrowing costs are jacked up by central banks. If global governments had to pay today's rates on all their existing debt, it would add $1.1 trillion to their budgets next year, Fitch Ratings calculates. That means, at a minimum, a squeeze on economies already struggling with a cost-of-living crisis. At worst, something in the global financial system may break. Recent history is rich in examples of large debt piles that turned bad, from Japanese corporations in the 1990s to US homebuyers and European governments in the following decades. Among possible weak spots now are the balance sheets of Canadian households, Italy's public finances and private credit markets in the US. Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Egypt are already discussing aid with the International Monetary Fund. Rising interest costs are "a slow-moving train for consumers and companies, just like for governments," says Sean Simko, global head of fixed-income portfolio management at SEI Investments. "At some point you are going to be watching it slowly creep up. And then all of a sudden it's going to be in your face. And then it's going to be too late."

—Simon Kennedy Afghanistan's economy faces little chance of aid given the Taliban's failure to break its international isolation since seizing power last year. The UN Development Program says the economy will shrink 5% in 2022 after contracting 20% last year, while the country's per capita income is projected to decline by 30% to $360 in 2022. At the same time, the cost of essential items such as food and fuel have climbed by about 40%, it says. "An isolated Taliban regime has a direct impact on the country's economy," said Madiha Afzal, a fellow in the foreign policy program at Brookings. "Beyond its frozen foreign reserves, it also finds itself unable to get development aid, something the previous Afghan government was heavily reliant on."

Global aid and funding account for 40% of Afghanistan's gross domestic product. The worst drought in decades and the Covid-19 pandemic have also added to the economic free-fall. Read more here. - Coming up | Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell speaks at the Brookings Institution in Washington, with investors betting he will sign up to slowing the pace of interest-rate increases in December.

- Jiang Zemin dies | The Chinese leader who presided over more than a decade of dramatic economic growth following the 1989 crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square, died at the age of 96.

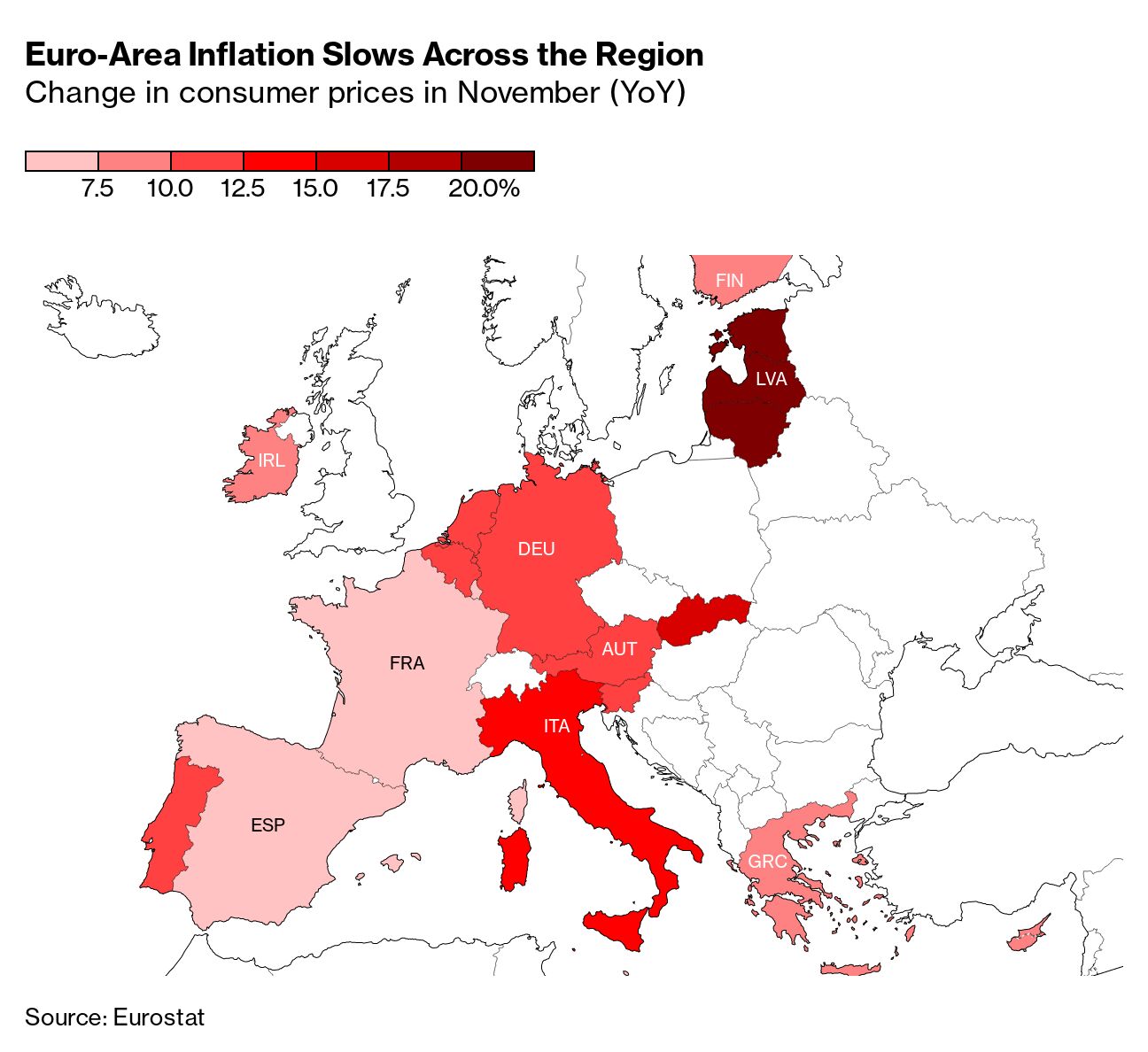

- New hope | Euro-zone inflation slowed for the first time in 1 1/2 years, offering a glimmer of hope to the European Central Bank in its struggle to quell the worst consumer-price shock in a generation.

- Japanese wages | Even staff at Japan's central bank aren't getting the pay raises Governor Haruhiko Kuroda believes are needed for stable inflation.

- China weakens | China's factory and services activity shrank further in November as record Covid cases prompted widespread movement curbs.

- US cracks | US labor markets are starting to erode for groups such as young adults, according to research by the Fed Bank of St. Louis.

- Canada sputters | Canada's economy is gearing down rapidly, potentially giving the central bank leeway to slow rate increases.

- Staying hawkish | Argentina's central bank expects to keep its key rate unchanged at 75% until at least early next year.

- Four day weeks | The first large-scale study of a four-day workweek has come to a startling close: Not one of the 33 participating companies is returning to a standard five-day schedule.

The US economy is going to struggle to beat back inflation because some older workers are never returning to the labor market, according to a BlackRock analysis. As of October, 1.3 million people have left the workforce after turning 64. Another 630,000 people didn't wait to hit that age before quitting. "The effect of this demographic shift on participation won't reverse without massive structural changes in workforce behavior over time," BlackRocks's analysts said in a report. "That implies the workforce will keep shrinking relative to the population. Economic activity will need to run at a lower level to avoid persistent wage and price inflation, especially in the labor-heavy services sector."

Read more reactions on Twitter |

No comments:

Post a Comment