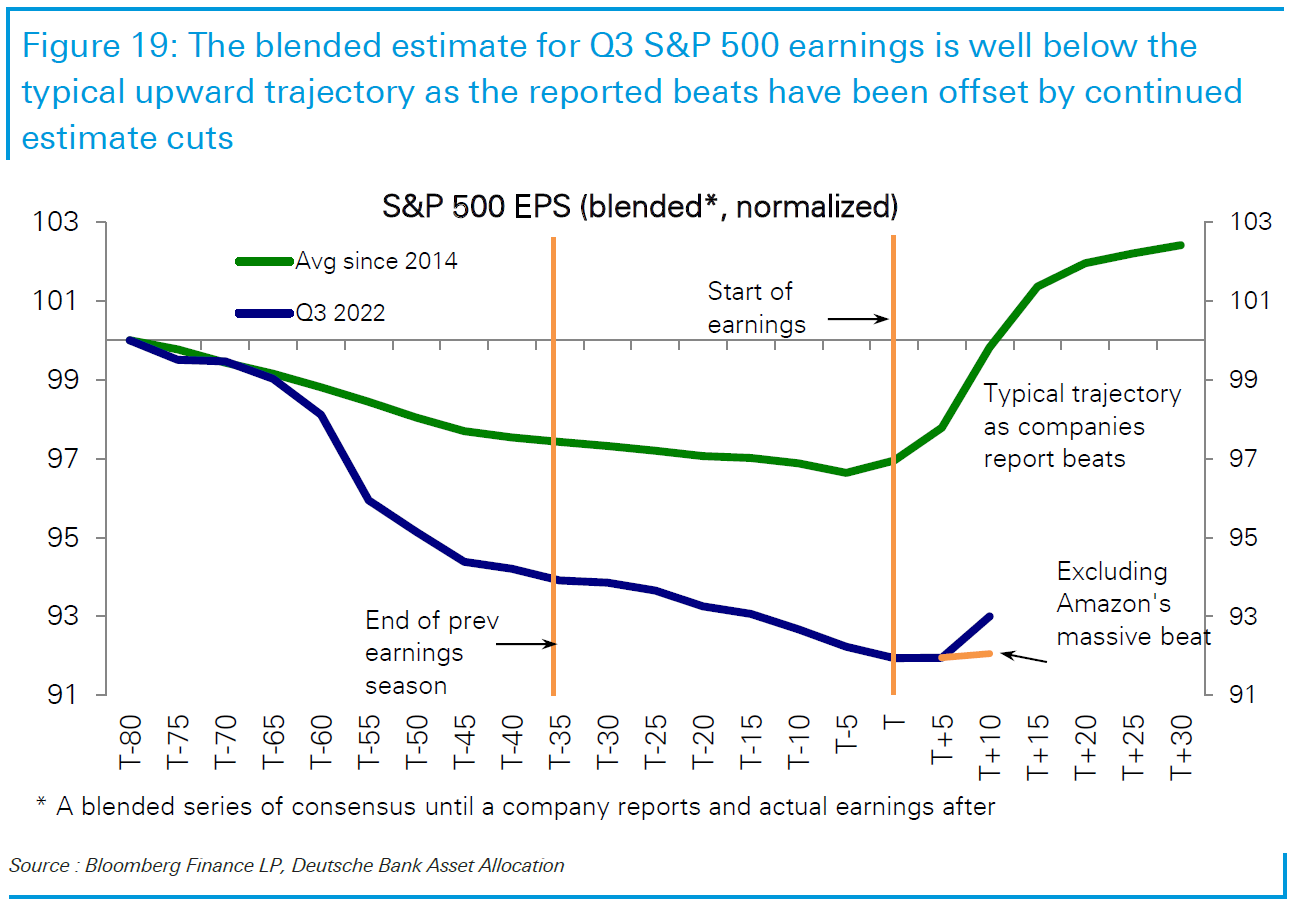

| Here's a conundrum. Corporate earnings season for the third quarter is over halfway through, and it's not been great. Spectacular disappointments (notably Meta Platforms Inc.) have outnumbered successes. And yet over the last two weeks, as companies have come clean, the S&P 500 has managed to gain 8.8%. What gives? Part of the problem is that the numbers are more varied than usual. Big tech companies generally disappointed, but there've also been some big successes. The aggregates don't capture this. One idiosyncratic result particularly skewed the overall data. Amazon.com Inc. reported earnings twice their forecasts — and yet the retailer's stock subsequently fell, because of its gloomy prognosis for holiday season sales. Include Amazon, and earnings per share for the quarter are beginning to turn up. Exclude it, and they're flatlining, as illustrated by this chart from Deutsche Bank Asset Allocation's Bankim Chadha:  The energy sector, for which earnings expectations for 2022 have doubled since the turn of the year, also skews perceptions. When energy is included, the S&P 500's earnings per share are still running ahead of projections at the new year. Aside from energy, only utilities and real estate (generally considered defensive) have risen so far in 2022, along with materials, where estimates have begun to fall as metals prices reduce: Why such positivity in the market response, then? Because even though this wasn't in their estimates, plenty of investors were worried about an all-out earnings crash. With the prominent exception of Meta, this hasn't happened. Stocks had had a discount applied to them, which has been removed as shareholders realized they didn't have to stay in the trench with their fingers in their ears. As Dennis DeBusschere of 22V Research puts it: Beat percentages have been skewed lower than normal, with more 5-10% beats than usual and fewer 10%-plus surprises. That is a BIG shift from even 2Q, when beats were skewed higher than normal. Earnings growth is slowing, which needed to happen. The reason this season has proven to be a positive catalyst for equities is that earnings are NOT crashing.

The relief that things weren't even worse has helped the slight pickup in earnings estimates for this quarter, from seriously low levels which according to 22V imply an imminent recession. And the general level of anxiety shows up in the way companies that beat estimates are being rewarded, and those that don't are punished. Reactions are far more extreme than usual, as illustrated by 22V: Christopher Harvey of Wells Fargo labels this "peak penalties for EPS misses": While large-cap firms are not in dire shape, post-earnings reactions suggest some of our early season concerns are being realized. The "bottom line" is that investors have been significantly less tolerant of EPS misses, with the average penalty for missing — -456 basis points — the worst we have seen in nearly a decade (average: -223bps; range: -115bps to -356bps). This has coincided with what feels like a particularly high number of EPS misses (24%) for being this far into a reporting season. The harsh penalties and total count suggest a non-negligible chunk of companies are falling short of what was we suspect were preemptively-lowered expectations.

The rewards for the good performers outside the tech sector show that optimism remains — and also that those good results in themselves imply that the economy is not in as dire straits as it appears to be. There have been a lot of them, as Michael Purves of Tallbacken Capital Advisors explains: It's remarkable that 32 stocks in the S&P 500 made fresh highs this week — in all cases spurred on by strong earnings reports. And while energy and defensive health care stocks accounted for much of these fresh highs, there were others such as McDonalds that performed well on earnings, and in their share price. Caterpillar did not put in fresh highs, but they had a strong report and their outlook did not reveal recessionary concerns.

A longer-term perspective also reveals that things aren't as bad as all that just yet (outside a few huge internet platforms). Earnings per share remain ahead of a very well-established growth trend, which stretches back to 1935. That makes further falls in future quarters particularly plausible. It also helps to explain why the market reaction hasn't been more distraught — corporate profits have been doing very well since the pandemic, and haven't declined all that much: Up until now, corporate earnings have turned equities into some kind of a redoubt against an economic recession. And earnings expectations for 2023 remain higher now than they were at the beginning of the year. This chart is also from Chadha, and shows that the market as a whole is still very much more optimistic than Deutsche's own house view: In other words, the equity market is still implicitly pricing in a "soft landing" for next year, and the results for many companies imply that there's a very good chance for it to come true. But now we enter the paradox that goes beyond the earnings conundrum. An 8% rally in two weeks makes people feel wealthier, and runs the risk of creating more inflation. If the market is going to stay this buoyant, it grows that much harder for the Fed to pivot. And while 2023 earnings expectations remain as robust as they are at present, it's harder to reach catharsis and a durable bear market bottom. Morgan Stanley's Lisa Shalett made this comment earlier in the earnings season, but it's still valid: We figured that the third quarter earnings season was likely to be the cathartic confessional, potentially setting up a 10% downward reset to 2023 earnings expectations and quick resolution to the painful bear market. Unfortunately, our optimism may have been premature. Instead… we sense that a series of muddled messages is emerging regarding earnings resilience, and they will extend this bear market and delay a recovery. The S&P 500 consensus estimate for next year needs to fall toward $212 per share.

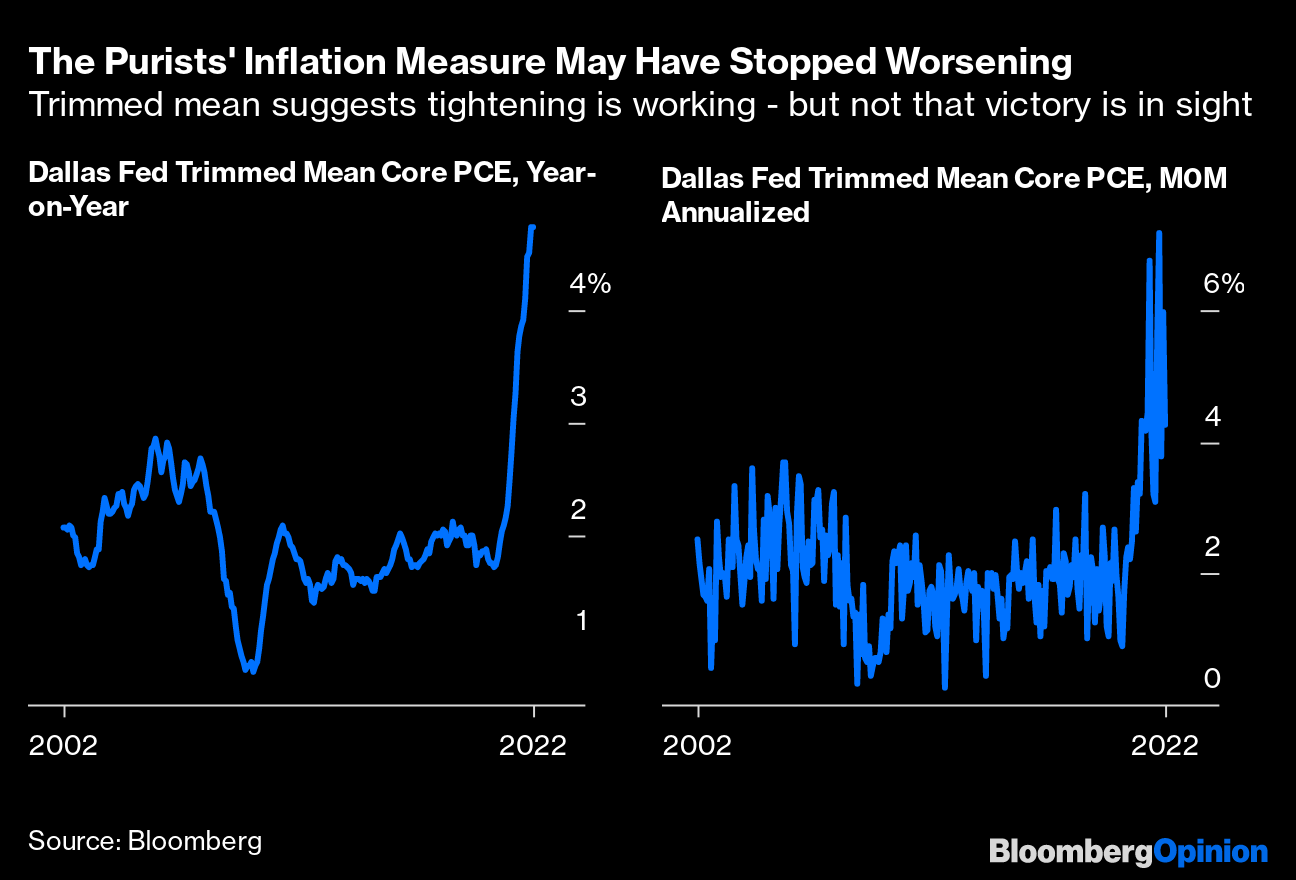

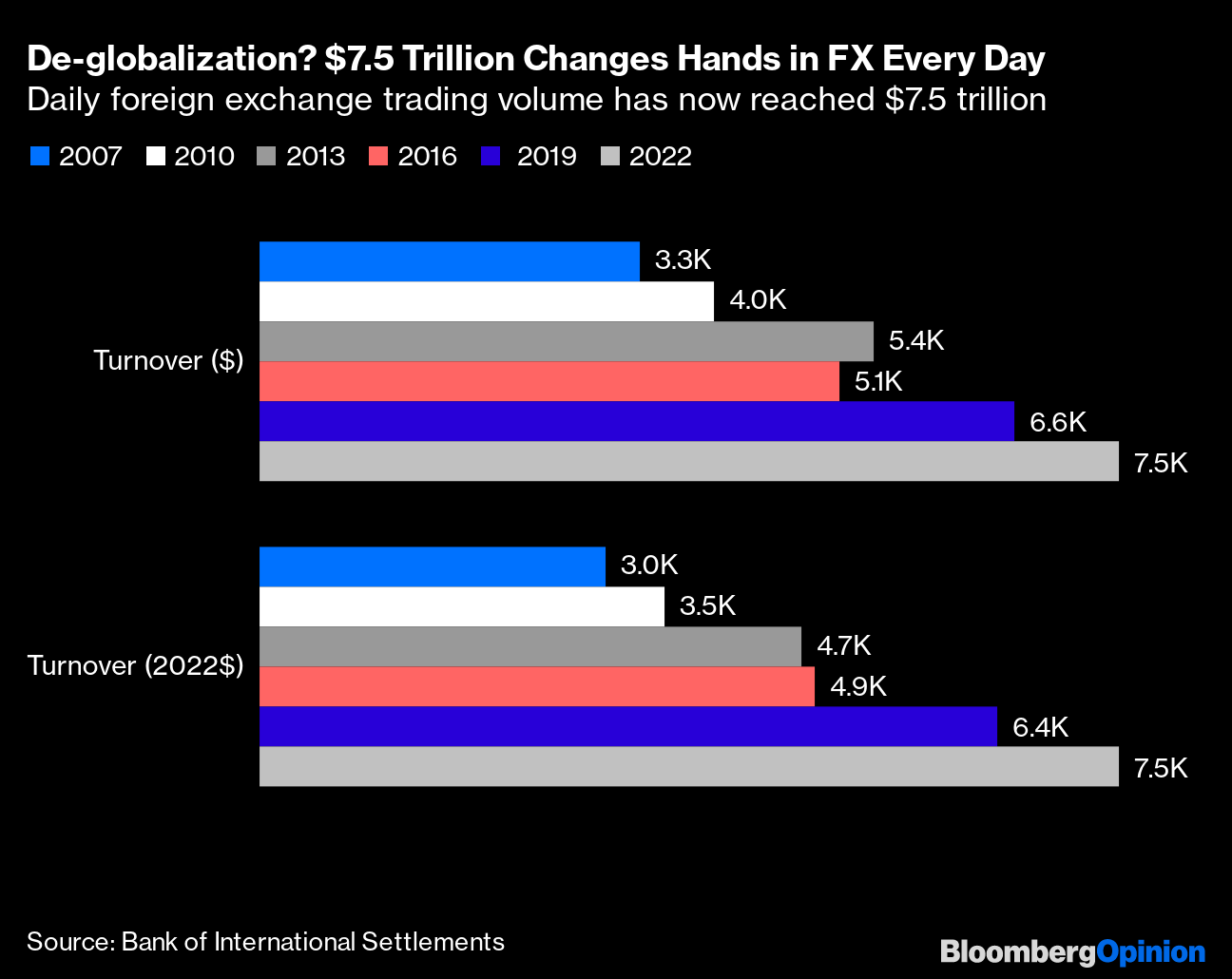

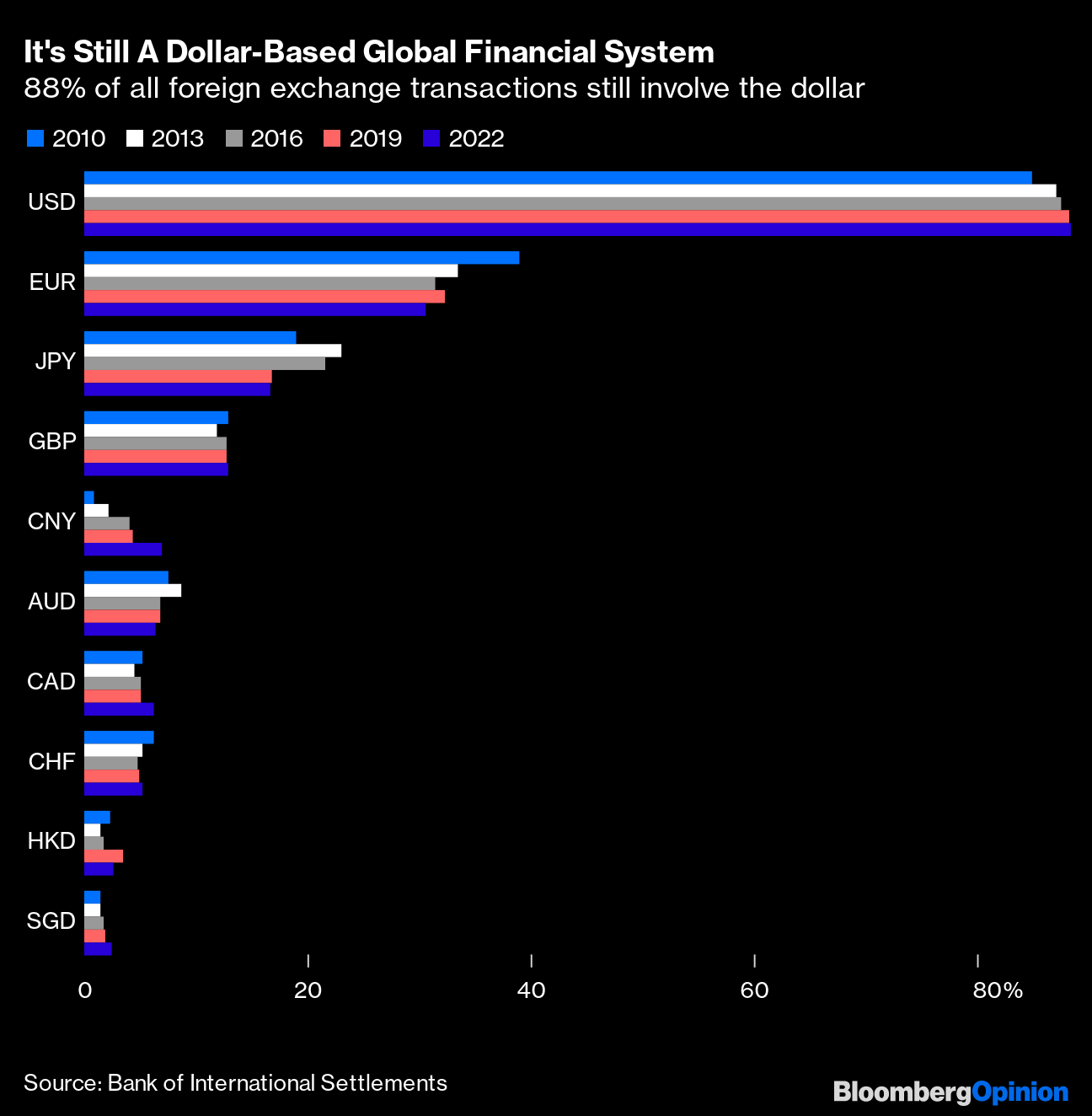

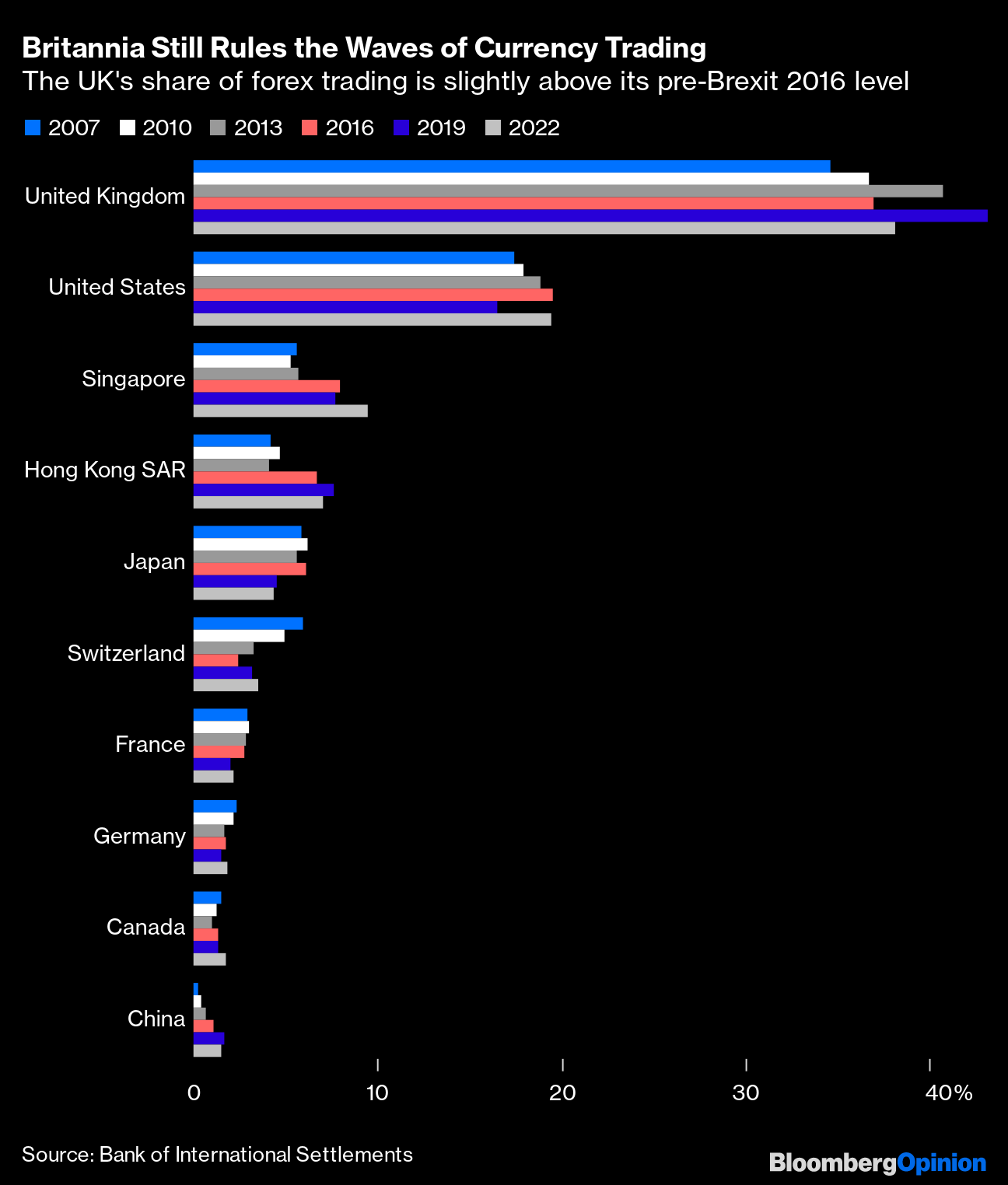

In short, particularly for the Fed, bad news might have been better. Which brings us to... —Reporting by Isabelle Lee The last significant data that the members of the Federal Open Market Committee will be able to view before this week's decision on monetary policy have arrived. They don't suggest any leeway for the bank to reverse direction; they also don't rule out the possibility that the Fed will signal that it's slowing the pace of tightening. Most important was the monthly publication of the PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) deflator, which is compiled as part of gross domestic product figures. It takes longer to compile than the better known CPI (Consumer Price Index) and so tends to cause less excitement, but the Fed takes it seriously. Core PCE is its favored target. For real inflation purists, perhaps the best hard-core measure of underlying inflation is the trimmed mean core PCE, in which the biggest outliers in either direction are stripped out, and an average taken of the rest. Last summer, this number stayed low, and was a critical part of the case by "Team Transitory" that the spike in inflation was only driven by a few sectors directly affected by the pandemic. Now, however, it's become one of the best items of evidence that this inflation isn't transitory. On a year-on-year basis, it is unchanged from August, more than two percentage points above the Fed's targets. And on a month-on-month basis, September saw faster price growth than in any quarter from 2002 until the beginning of the pandemic. Neither measure worsened last month; but neither gave any reason to believe that victory over inflation had already been assured:  Friday also brought the latest installment of the employment cost index, which only comes out quarterly. This showed a very slight reduction in the inflation of the cost of employing people, but costs are rising at a 5% annual clip — still far too high for comfort: None of this provides grounds for the Fed to do anything other than keep making money more expensive. But last week's news from the Bank of Canada (which hiked by only 50 basis points rather than the expected 75) and from the European Central Bank (which gave itself the freedom to slacken the pace of tightening ahead) has rekindled hope that a "pivot" toward easier money lies ahead. This looks a stretch. At the time of writing, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has been declared winner of Brazil's presidential election, having won slightly less than 51% of the vote. He was a pragmatist during his first eight years in office, from 2002 to 2010, and it seems reasonable to hope that this narrow margin (the tightest election Brazil has ever had) will be a further inducement towards centrism. Two key points remain unclear at this hour: First, is the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro going to accept the result? One Brazilian newspaper that is well connected with the administration has been briefed that he won't be calling to concede, but won't contest the result either. Bolsonaro had expressed deep skepticism about the voting apparatus (run by his own government), and come much closer in the official count than had been expected. If he does go quietly, great. If he contests the result, or his supporters resort to violence or even try to push the notion of secession, that could be disastrous. Secondly, we need to know about Lula's economic team. The speculation is that Henrique Meirelles, central bank governor during Lula's first presidency and subsequently a finance minister, might be asked to return to the treasury. If he did, that would be regarded as very market-friendly. But Meirelles said on election night that he hasn't yet discussed it with the president-elect. So, there's still some uncertainty to be resolved. A calm and peaceful transition to a pragmatic government would make Brazil look like a great investment; but some of the other more alarming possibilities need to be eliminated first. Last week, the Bank of International Settlements published its triennial report into foreign exchange and over-the-counter derivatives markets, which you can find here. There's a mine of information, and it's worth going through the details. Here are what struck me as three of the most important points. First, there is no evidence at all of de-globalization. The world economy has generally grown at a disappointing rate over the last decade, and the Global Financial Crisis was predicted by many at the time to lead to "de-financialization" — a steady reduction in the amount of trust placed in markets. It hasn't happened. Total turnover has now reached $7.5 trillion each day in foreign exchange markets. In a year, that implies total turnover of not far short of $2,000 trillion, or to give its proper name, $2 quadrillion. The world's total gross domestic product for this year is expected to come in a little above $100 trillion. There's an awful lot of trading going on, and it's hard to see how anything like this amount is needed to cover the demands of trade or tourism:  Second, nothing has happened to dampen the power of the dollar within the system. Indeed, it is part of 88% of all currency trades, which is slightly greater than it was in 2010. (As there are two currencies involved in each trade, the numbers in the chart will sum to 200%.) The euro has dropped over that period while the most significant increase in trading volume, as might be imagined, is in the Chinese yuan. However, as the yuan is still significantly less widely traded than the pound sterling, the full entry of China into the global financial system remains a work in progress:  Third, geography and history still count for something. London continues to host far more currency trading than anyone else, despite the receding importance of the British economy, while the significance of the old imperial ties that helped establish the City's preeminence can be seen in the fact that Singapore and Hong Kong finish third and fourth on the list. London's position in the middle of global time zones, and the large pool of talented workers it now offers, have allowed the City to stay dominant:  For the continuing debate in the UK over whether Brexit was a good idea, this cuts both ways. Building up the City as a financial center now looks like a dubious route to growing the nation's economy, because London is already about as dominant as it can be. This was one of the hopes of Brexit, and it seems unlikely. However, there were also widespread concerns before the 2016 referendum that Brexit would damage the City's position and cause banks to relocate to continental alternatives like Amsterdam, Paris or Frankfurt. Compare the numbers for 2016 (and usefully, the BIS conducted its survey in April, two months before the referendum) with the latest numbers, and there is no sign that Brexit has done any damage to Britain as a financial center just yet. Halloween is upon us, and Alexandra Petri of the Washington Post has this top 50 list of Halloween party songs. There are some good ones in there, but I might add Ghosts by Japan, Spellbound by Siouxsie and the Banshees, Enter Sandman by Metallica, Spooky by the Atlanta Rhythm Section, Ghost Town by The Specials, Magic (from Ghost Stories) by Coldplay, or White Rabbit by Jefferson Airplane (not really Halloween-related lyrics, but just about the spookiest song there is), or Devil May Care or Old Devil Moon by Miles Davis. From the classical canon, I'd add Faust's descent into hell, to be greeted by demons, in Berlioz's Damnation of Faust (the Russian subtitles won't help much, but it's pretty clear what's going on), Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain (as made famous in Fantasia), or Mendelssohn's Die Erste Walpurgisnacht. If you want something more thoughtful on Halloween, there are discussions of it in Adam Tooze's Ones and Tooze podcast, and in Tim Harford's Cautionary Tales, which are both well worth a listen. Enjoy Halloween everyone, and let's hope for more treats and tricks.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. |

No comments:

Post a Comment