| There was a time when we talked about "Chimerica" to denote the tied-at-the-hip relationship between Chinese manufacturing and American consumption. In the aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis, there was a lot of angst about that relationship ending abruptly for politically-driven reasons.

That kind of sudden rupture didn't happen and China was, in many ways, the country that pulled the global economy out of recession after the Great Financial Crisis. Having been an increasingly important engine for growth and a source of disinflation over decades, China stepped up to the plate back then. The situation now, though is very different. The country is going through what Premier Li Keqiang recently called its worst patch of growth of the pandemic. The slowdown is so vexing, we're now getting discordant messaging from China's leaders. So instead of being a savior, China could in fact be a burden to the global economy: acting as a drag on growth and potentially even exporting more inflation due to broken supply chains.

That's potentially bad news for the world as a whole. But for America, maybe it doesn't matter quite as much as it once did. Even before the pandemic, some gradual and subtle drifting apart had come to pass, and Covid seems to have given that a boost. US consumption is holding up well and even though markets are flagging concerns about growth, recession is far from a foregone conclusion.

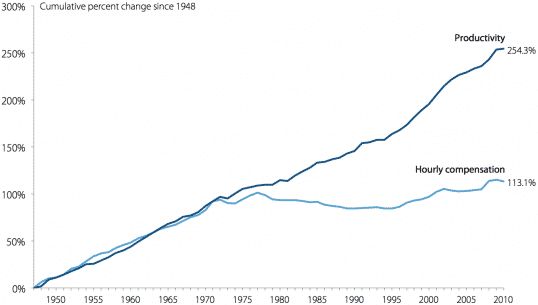

One other leg to the US-China relationship that bears examining is the effect of Chinese savings. The glut of extra money spilling out from China has provided a significant boost to global risk assets — in particular US equities. A combination of more spending and/or slower growth in China, ultimately means less to invest abroad, removing a key tailwind for US stocks, which are already taking a beating amid the prospect of slower American growth and higher borrowing costs. A couple of last points on supply chains. The transition to regional supply chains will be expensive. Supply chain resiliency implies duplication, inventory buffers and proximity to customer at the expense of efficiency and cost. Some of those costs will be borne by end consumers. And that means higher inflation. And when you have higher inflation embedded in the system, policy makers have to make a choice on whether they're willing to accept that inflation, say 3% inflation, instead of 2%. The silver lining in all of this is that after years of wages lagging productivity growth, we could be on the cusp of wages catching up. If you look at US productivity growth, the post-World War 2 trend is solid. But from the 1970s onward, hourly compensation stalled. And the gap is now enormous.  Source: EPI Source: EPI The onshoring of supply chains makes it more likely this will change. So, in the end, there are some reasons to be optimistic. While the changes within China and between China and the US likely mean higher inflation, they also could mean higher wages as a proportion of output. Once we get through the immediate inflationary surge — and the policy response -- the economic landscape for ordinary workers could be a lot better than it has been in a long while. |

No comments:

Post a Comment