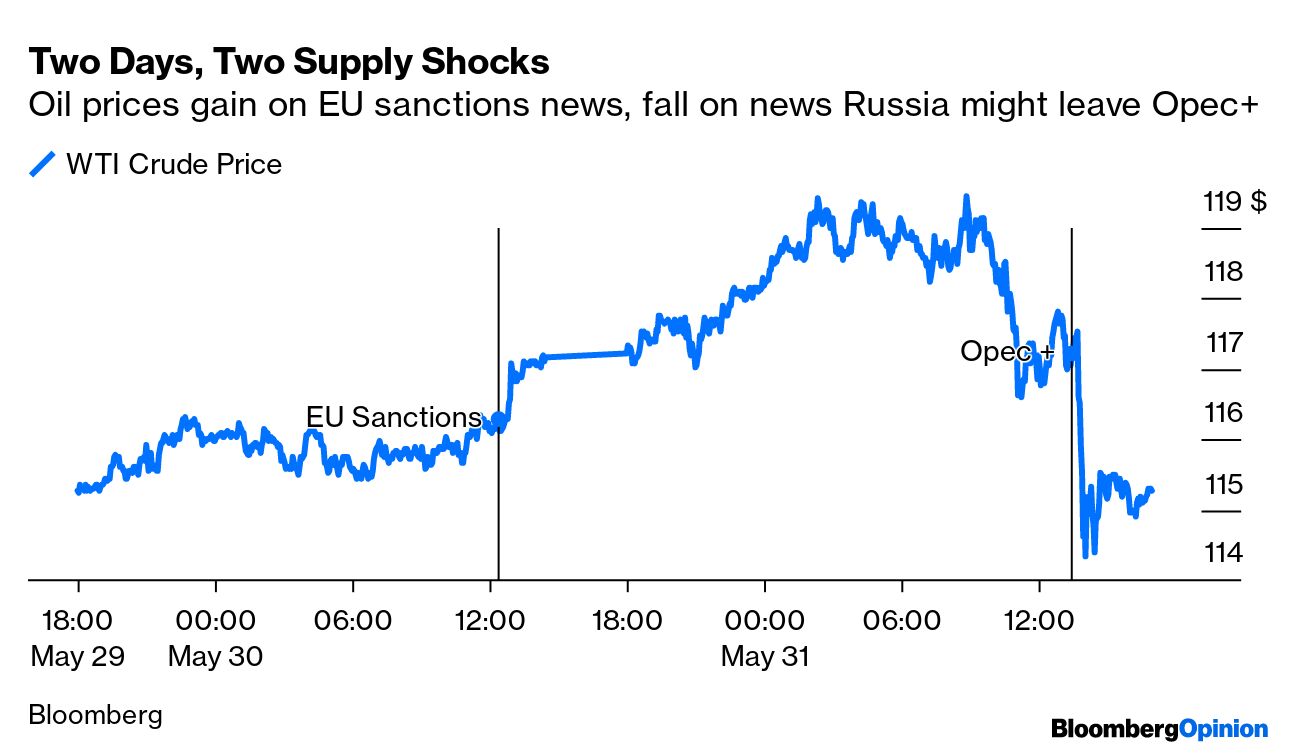

| There's a difference between strategy and tactics. It's as well not to get them mixed up. This applies to central bankers, stock and bond investors, politicians, and military leaders. The distinction is important to keep in mind at a time like this. The last week or so has seen a switch to a "risk-on" narrative, as investors bet that central banks won't have to raise interest rates so much after all. If that's right, then of course you should buy bonds. That pushed down their yield — which justifies paying a higher price for stocks. This signals the demise of TINA, or There Is No Alternative (to stocks), and her replacement by TARA: There Are Reasonable Alternatives (to stocks). To see how enthusiastically investors are now trying to buy the dip in bonds, rather than stocks, look at exchange-traded funds. In the last few months, shares outstanding in the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond exchange-traded fund (generally known by its ticker symbol of TLT), have surged, even as the share count in rival stock market tracking ETFs has dropped a little. This means that there is pressure from new buyers, which requires the creation of new shares:  Obviously the dip-buyers are taking the chance to invest at a relatively generous yield. For institutional managers trying to guarantee liabilities for pension funds or insurers, this is a matter of strategy, rather than tactics — if you can buy at a yield that eliminates your risk, you do it, even if there is a chance you could have made more money by waiting. But the weight of money from retail investors playing with ETFs suggests that they also see this as a good strategic call, rather than a tactical ploy when a market is temporarily oversold. Jean Ergas, chief economist at Tigress Financial Partners in New York, suggests this is a classic confusion of strategy and tactics. The current risk-on rally gained force last week when the minutes from the Federal Open Market Committee's May meeting failed to provide any fresh hawkish surprise, and then Raphael Bostic, head of the Atlanta Fed, commented that the central bank might want to "pause" its campaign of hikes in September. This was the most dovish utterance by a leading figure at the Fed in a while, but Ergas suggests that Bostic was talking tactically, not strategically. He was suggesting it might be an idea for policy makers to give themselves more flexibility with a pause later in the year, not that the Fed might already be finished with its tightening campaign by the end of the summer. The market took it as a strategic announcement. Treasury yields rose sharply Tuesday (although they're still well below their highs from a month ago) after Fed Governor Christopher Waller said that he thought 50 basis point hikes might be necessary at "several" meetings. That presumably means three or more. He was talking strategically.  | A similar problem might be at work for active managers in the stock market. Equity hedge funds had a good time of it in 2020 and 2021, largely through correctly betting on the FANG internet platform stocks to profit from the pandemic, and from low interest rates (which flatter the valuations of growth companies for whom most of their value is tied up in cash flows still long in the future). This was a brilliant tactical move. Unfortunately, they seem to have treated it as a matter of durable strategy. Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s chief U.S. equity strategist, David Kostin, keeps a basket of "hedge fund VIPS" — the stocks that show up most prominently in hedge funds' portfolios. They outperformed spectacularly last year and in 2020, and have come right back to earth this year. This tactical retreat stands to be very damaging. Most of the VIPs are FANGs, the big companies that most of us know all about anyway. Clients might just start to ask why they paid hedge fund management fees to someone to buy FANG stocks for them. All of this pales in comparison with the conflict in Ukraine, now into its fourth month. Initially, much of the world was braced for the Russian military to win a swift and crushing victory. That didn't happen. Russia's attempts to take Kyiv or even the second city of Kharkiv appear to have been abandoned. Instead, they are waging a tougher and far more limited war of attrition in Ukraine's far east and on its southern coast. Meanwhile, the European Union continues to levy much tougher sanctions than seemed feasible three months ago. The question: Was the initial chaotic Russian assault on the capital a failed strategy, or was it a tactical move to divert attention from the true intention, which had always been to establish a land bridge to the Crimean peninsula and dominate the coast? Is Russia in fact winning, despite everything? I don't know. Much discussion of this in Western media sounds like the grinding of political axes. But this matters a lot. There is one school of thought that "what happens in Donbas stays in Donbas," in the immortal words of Clocktower Group's Marko Papic. In other words, Ukraine and Russia had a territorial dispute over the easternmost part of the country that dragged on for years without ever much affecting the markets. The West can soon stop paying attention, and this is already happening in markets. But if Russia is in fact engaged in a successful strategy, then everyone needs to pay attention. It has now blockaded Ukraine's Black Sea ports, which means that it has put a stop to the country's agricultural exports. Those are critical for many countries around the world. The impact on agricultural prices makes inflationary pressure sharply worse. With Ukraine reduced to a landlocked country, its room for maneuver is much reduced. Russia's position in any negotiation grows far more powerful. And its oil still has buyers around the world, who are paying prices that keep its economy running. That prompts Ergas of Tigress to suggest that the market is dangerously underestimating the risks: "The market have been thinking of this in terms of Value-at-Risk," he says, referring to risk models where the potential returns each day are held to follow a normal bell curve distribution that can be predicted from past performance. "VaR isn't good for tail risks. It never tells you how much you're going to lose in an extraordinary event. And Putin is in power and will stay there; the market is understating the extent to which this man can do things like cut off the gas." Other risks in the Ukraine situation remain terrifying, and are barely reflected at all in markets. It could easily expand to include more countries. And it could easily escalate, which would logically bring about the use of tactical nuclear weapons. News that the U.S. had decided against letting Ukraine have missiles that could be used to attack Russian territory shows that this is a real risk that the U.S. can clearly perceive. A protracted war is bad for everyone. Sanctions and a blockade could soon add up to stagflation, and raise the risk of unrest over food prices across the world. But it's hard to see how this can be avoided without someone admitting a crushing strategic defeat. If there is one dimension to the Ukraine conflict that matters more than any other to financial markets, it is of course its effect on oil. Here again, the strategy needs to be thought through many steps at a time. Control over a big oil supply is Russia's greatest strategic advantage, and western Europe's crucial point of weakness. Any shift in this strategic balance more or less automatically shifts the inflation calculus for the rest of the world. To demonstrate, this is how the Brent crude price moved in the first two days of trading this week:  Oil surged late Monday (the times are Eastern daylight) as it became clear that the EU believed it could make tough sanctions stick. That meant denying itself supply, and accepting that prices would drive higher. Having nearly touched $120 per barrel, however, Brent tanked 24 hours later over news about OPEC. The biggest Middle Eastern oil producers might have been able to strangle the Russian war effort in its infancy by upping oil production and tanking the price. They didn't do this, prompting fierce criticism of the Saudi Arabians in particular. But a Wall Street Journal story saying that Saudi Arabia and others were now planning to exclude Russia from OPEC+ supply controls had a galvanic effect. If that means that traditional producers are now prepared to pump all the oil that was previously going to be supplied by Russia, then prices can tumble a lot further. Europe's strategic position grows much stronger and Russia's no longer looks impregnable. No wonder oil dropped. Its future direction depends above all on the strategic calculations made by the leaders of the world's biggest oil importers and exporters. The normal tools of macroeconomics look increasingly inefficient in the face of the need to understand how that grand game will play out. That brings us to the political impact of all of this. High fuel prices are bad for incumbent politicians. In particular, they're terrible for presidents of the U.S., where many are dependent on cars and relatively low taxation means increases in crude costs translate swiftly into higher prices at the pump. Gas prices are now very high, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration: Dan Clifton of Strategas Research Partners points out that this chart is almost like a perfect rendering of presidential approval ratings over time. Despite everything, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush kept quite strong popularity as gas prices stayed low. Confidence in Bush collapsed as gas prices eventually went through the roof; and what's happening now has had a horrible effect on Joe Biden's ratings. No wonder he had a well-publicized chat with Jerome Powell of the Fed on Tuesday. Inflation is now a political problem of the highest magnitude. That's likely to hand both houses of Congress to the Republicans after November's mid-term elections. Such a result would likely render the U.S. even less able to take coherent action than it is at present. What can Biden and the Democrats do to avert this in the next few months? They will be thinking tactically as well as strategically — and so should investors looking to allocate capital. Let me return to the fraught topic of American gun control. I argued last week that it was dishonest to argue that the 2nd Amendment to the constitution, which says that the right to bear arms "shall not be infringed," made it impossible to take any measures that might help to stop disturbed young men getting their hands on weapons of war. The same, I argued, applied to the interpretation by the Supreme Court in the 2007 Heller judgment, written by the arch-conservative jurist Antonin Scalia with a scathing dissent by the liberal lion John Paul Stephens, that the amendment guaranteed a personal right to keep arms in the home, and not only a right to organize a well-regulated militia. Neither Scalia nor Stephens are with us anymore, but I was fascinated to read this op-ed in the New York Times by the clerks who worked for the two great justices on Heller. They make clear that they still disagree profoundly about that judgment, but both state adamantly that Scalia's opinion doesn't thwart sensible extra gun regulation, such as background checks or raising the age limit. Both seem angry that politicians are evading their responsibility by hiding behind judges. They're much better placed to make that judgment than a financial journalist typing out a newsletter, and I commend their conclusion that rather than resting on the Heller judgment: all sides should focus on the value judgments and empirical assumptions at the heart of the policy debate, and they should take moral ownership of their positions. The genius of our Constitution is that it leaves many of the hardest questions to the democratic process.

Amen to that. Maybe we can all survive after all. More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion: Want more from Bloomberg Opinion? Terminal readers head to {OPIN <GO>}. |